Accents of the Caribbean: How vowel pronunciations pivot, shift and merge

James Walker has collaborated over the years, first with Jack Sidnell and then with Miriam Meyerhoff, to research the language, grammar and accents of English in the Eastern Caribbean. More recently, Walker and Meyerhoff turned their attention to understanding in greater detail variation in vowels amongst the different communities of the island of Bequia in the Eastern Caribbean.

Bequia (pronounced BECK-way) has about 5,000 inhabitants and is the second-largest island of the 32 Grenadine island chain, only nine of which are permanently inhabited. Bequia is part of the country of St Vincent and the Grenadines, lying just nine miles south of St Vincent and 100 miles west of Barbados. Described as an exquisitely beautiful Caribbean island of seven square miles, this remote and tranquil island has a history of settlement by people of diverse origins over the last few centuries. In the eighteenth century, when the island lacked permanent inhabitants, France claimed it as its territory, but later ceded it to the British in exchange for other Caribbean islands. The British settled some of their citizens on Bequia and brought slaves. A plantation economy was established with varied crops grown for export, including sugar for producing rum. Once the slaves were emancipated, the plantation economy collapsed, and the island shifted to a maritime economy alongside small-scale subsistence farming. It is today an island popular for tourism and yacht cruises. Alongside its sandy beaches with coconut palm trees and turquoise waters, visitors are charmed by its small villages, winding streets, scenic walks and the warm welcome from Bequia’s relaxed and friendly people.

“Until recently, these communities were not characterized by a high degree of social interaction with each other or with off-islanders. This situation changed dramatically with the building of the airport in 1992 and the development of tourism and yachting…”

Different communities have evolved on Bequia based on different socio-demographic histories. Some inhabitants descend from the emancipated slaves, while others are linked to British settlers, and there are also more ethnically mixed communities. Historically, these distinct communities were relatively isolated until 1992, when improved air transport enabled greater social interaction. Today’s current inhabitants descend from African, British, American, Portuguese and Carib Island people. English is the official language of the island, with a distinctive Creole or Caribbean English spoken widely. The English and creole spoken on the island contain elements of Carib, African, English, French, Spanish and Portuguese languages, and reflect the diverse ethnic and linguistic origins of the people.

The remote and tranquil island of Bequia has a history of settlement by diverse nations and people across the last few centuries.

Accents of English

English is widely spoken around the world, with differences among dialects and accents based mainly on vowel pronunciations. Accents are usually acquired by ‘transmission’, when children learn the pronunciation of words from adults and other children. In addition, dialects and accents may also be formed through non-English speakers acquiring English as adults, introducing new pronunciations which may then be transmitted to and reinforced in future generations, giving the community unique sounds with a distinctive accent.

Vowel mergers and low-back vowels

Walker explains that vowel pronunciations are not static: they change over time. One way in which differences in pronunciation change is through the merging of vowels. A vowel merger takes place when words with historically distinct vowels are pronounced the same. For example, in the Canadian English spoken by Walker, the ‘o’ in a word like cot and the ‘au’ in a word like caught are pronounced the same, whereas the difference is maintained in the New Zealand English spoken by Meyerhoff. There are different views about the relation between vowel mergers and creole languages: some studies suggest that mergers are highly characteristic of creole vowel systems, whereas other studies do not support a clear distinction between creole and non-creole systems.

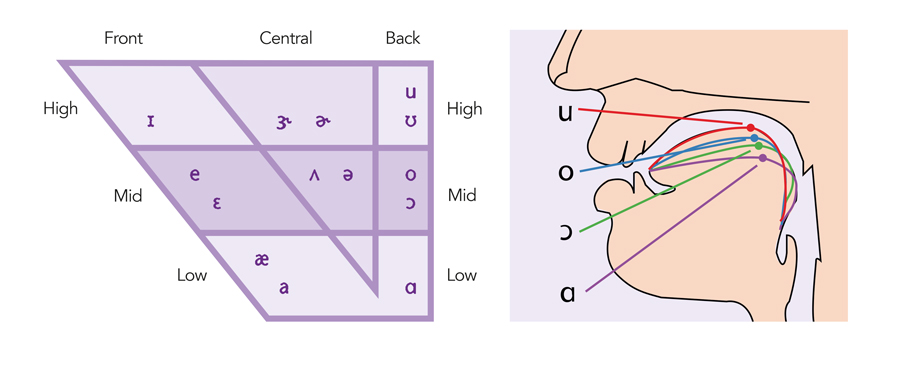

Vowels are produced by opening the mouth to different degrees and placing the body of the tongue in different parts of the mouth to alter the airflow. One area of the vowel space is the ‘low-back’ region, produced with the mouth wide open and the tongue lowered, with the vowel articulated at the back of the tongue, in words such as lot, thought, palm and father.

Pivots in language

There are moments in time when there is a high potential for vowel pronunciations to change, which has implications for the way that accents develop in the future. Such times include those when people from different regions begin to interact more widely due to improved travel access that renders an area less remote. Additionally, the influx of people to a new region, who bring their own acquired pronunciations of local languages, can also result in pivots of the vowel system. According to Walker, one of the main areas in which pivots of pronunciation have occurred historically is in the low-back vowel space. Understanding these pivots has been enabled by large databases of spoken language and the development of speech-language technology and software.

Although the English spoken in countries such as the UK and US has been studied quite extensively, there has been less research on vowel systems in countries where an English-based creole is spoken, such as St Vincent and the Grenadines. Walker and colleague Meyerhoff thus set out to explore the extent to which low-back vowels in Bequia are differentiated from each other. The research team also wanted to explore whether speakers in Bequia use the low-back vowels to differentiate where they live, and additionally, test the applicability of speech-language software for non-mainstream English accents.

Bequia low-vowel systems

The research team chose the Bequia villages of Hamilton, Mount Pleasant, Paget Farm and La Pompe for this study, as each of these has different economic and cultural characteristics. Young residents were recruited to conduct audio-recorded conversations with 62 village residents, aged 32 to 100 years of age. Out of them, Walker and Meyerhoff selected 13 women and 10 men to represent the villages in a study of the vowel systems. The transcribed conversations were imported into software applications (ELAN and FAVE) to measure the acoustic properties of 130,732 vowel pronunciations.

Speakers from the different villages could be distinguished phonologically through careful acoustic and quantitative analysis.

Walker and Meyerhoff used mixed-effects linear regression models to analyse differences in the positional and durational measurements of the vowel pronunciations of individual speakers. They found that speakers from different villages could be distinguished through careful acoustic and quantitative analysis. The analysis indicated that the villagers had very similar vowel distributions, except for four low back vowels (represented by the key-words CLOTH, LOT, PALM and THOUGHT), where there were differences in the position and duration of pronunciation, mainly between the THOUGHT and CLOTH vowels. The differences between Mount Pleasant and Hamilton are greater than those between Paget Farm and La Pompe. However, in contrast to research they have conducted on grammatical variation between villages, differences in vowel pronunciation do not allow for distinguishing one village as being more ‘creole-like’ than another.

“These results also suggest that speakers in Bequia have resolved the pivot of the low-back vowels in different ways: some distinctions among vowels have been maintained (either through frontness/backness or duration), while other vowels overlap to different degrees.”

Walker and Meyerhoff conclude that despite a high degree of similarity between the different villages of Bequia in their vowel systems, there are differences in the pronunciation of some of the low-back vowels. Their research has shown that accents are a reliable indication of the region on the island people come from. However, the resolution of vowel pivots over time may have been less straightforward than previously considered in differentiating accents. When adult speakers learn a language through diffusion, there tends to be a greater interruption and restructuring of linguistic systems than when children acquire a language through transmission. Bequia English has its origins in both language transmission and diffusion, which is likely to have impacted the evolution of English on the island.

This research is based on older generations of speakers of Bequia English. Future research with younger generations, who are more mobile, educated and exposed to a wider range of varieties of spoken English, may reveal different patterns of vowel mergers and shifts and whether younger generations maintain vowel distinctions to differentiate the place they come from, as well as the extent to which low-back vowels act as a pivot for other vowels to shift.

Personal Response

How did you become interested in understanding variations in people’s accents?

<> James Walker: I grew up in Canada, but my father and his parents came from Yorkshire in England, so I was aware from a young age that there were other ways of speaking English. It was only when I went to university and started studying Linguistics that I acquired the intellectual tools to understand where these differences came from. Studying the history of English gave me a deeper understanding of how different accents have arisen.