The evolution and spiritual journey of two former Black Panther Party members: George Jackson and Eldridge Cleaver

George Jackson and Eldridge Cleaver were two Black activists who came from similar circumstances and viewed racial injustice with the same passion. However, Dr Trevin Jones, of St. Louis Community College, is interested in exploring how they each ended their lives with a very different mindset. Jackson was “consumed by rage” while Cleaver was “transformed by love”. Dr Jones tells their stories and, in doing so, reveals how each man contributed to the concept of manhood, particularly as it applies to African American prisoners and activists.

Two different narratives: Jackson and Cleaver

There are many similarities between Jackson and Cleaver. They are both African American males who were members of the Black Panther Party (BPP), and both spent significant time in prison. They were both passionate about overcoming the social injustices committed against Black people in America, while also struggling to understand their own identities. However, Jackson was consumed by anger, becoming increasingly militant until his death, whereas Cleaver became increasingly vulnerable after time spent in solitary confinement while in prison and later fleeing America as a fugitive.

Dr Jones states that both men helped to change the narrative surrounding Black males in America. They were both critical in helping incarcerated African Americans to re-evaluate their identities and to evolve as men. However, Cleaver’s spiritual beliefs allowed him to evolve more positively as a man, while Jackson was far more focused on developing his intellect and achieving social justice than he was on appeasing others.

Jackson helped Black men to feel rightfully enraged by the mass incarceration of African American males in the United States prison system. The BPP was militant and showed bravado in the face of police brutality. This exemplified a particular conception of masculinity which was defined by brashness and anger. Cleaver’s spiritual awakening marked a move away from this perspective, representing a split in the ideology of the BPP.

Rage and incarceration

In his younger years, Cleaver admired the ‘masculinity’ embodied by BPP founder Huey Newton, who engaged in gunfights with the police. Cleaver observed brutality towards the Black community and believed in the right of African Americans to stand defiantly against this injustice. Reacting with violence was seen as a form of legitimate liberation from the oppression of white society.

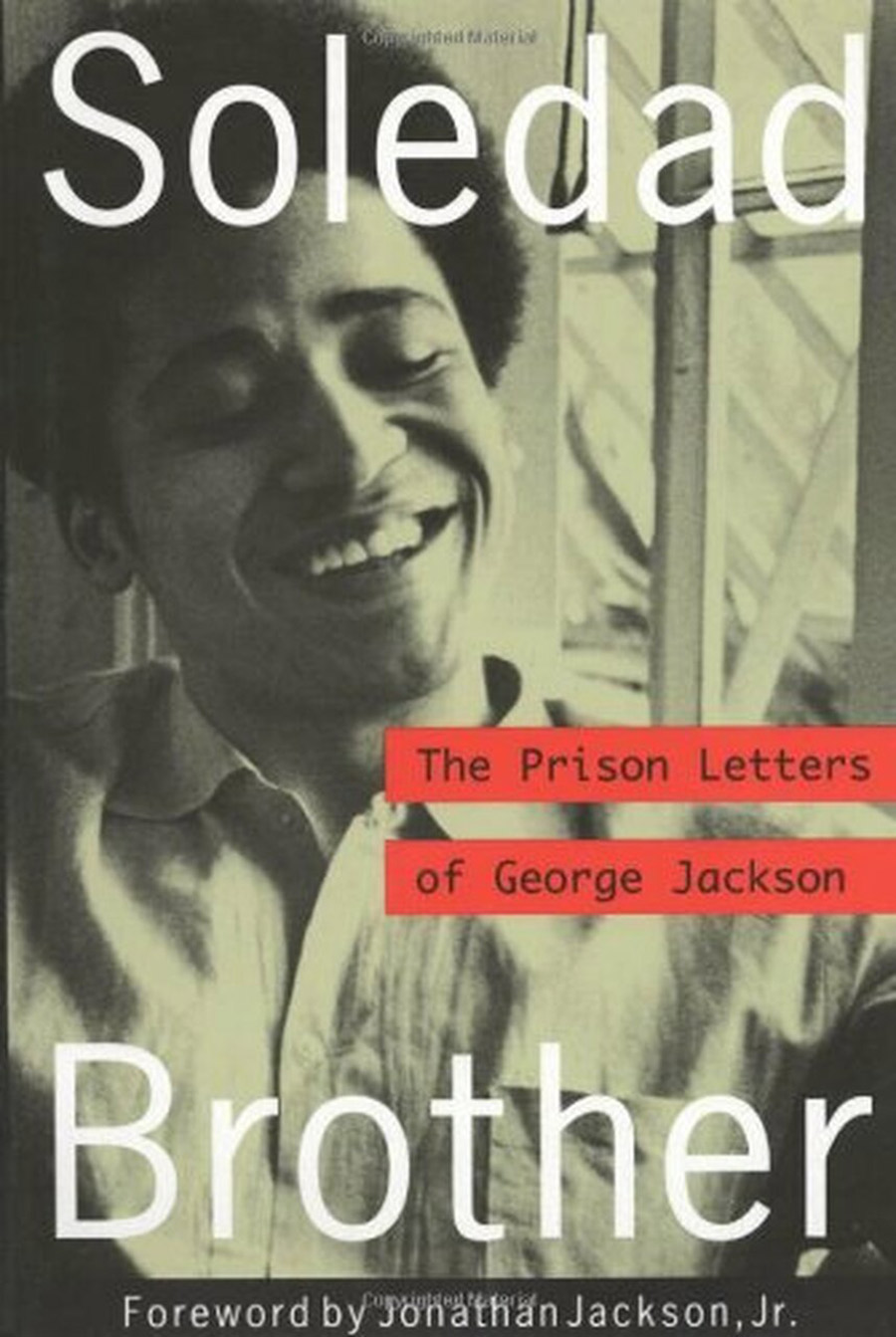

While in prison, Jackson remained closely associated with the militancy of the BPP. In writing his book, Soledad Brother, he became well-known as a revolutionary on the inside, highlighting the plight of Black prisoners. It was his view that prison was not populated by inherently bad people but by the poor, uneducated, and oppressed. This, he believed, was ultimately the fault of corrupt oppressors.

Entering prison aged just 18, Jackson spent much of his time learning to understand American law and how it helped to secure the status of Black Americans as second-class citizens. He admired Cleaver for being able to remain a central member of the BPP. All around him, Jackson saw prisoners becoming dehumanised, disaffected, and apathetic towards racial injustice. He feared that he would leave prison without the energy to maintain the fight. Therefore, he needed to maintain his revolutionary stance and encouraged his fellow inmates to feel the same sense of social and political insurgency.

In working-class, inner-city communities, hypermasculinity can be seen as a sign of strength.

The challenge for the African American male

Jackson’s narrative remained one of despair and rage until his death from a gunshot wound during an attempted escape in 1971. In his letters, Jackson revealed his rejection of God and the values instilled upon him by his mother. He viewed religion as a construct by white people that was used as a crutch by the weak and vulnerable.

Although his death was officially ruled as self-inflicted, Jackson’s supporters believed he was killed by the prison guards. In response, they began rioting, perpetuating an attitude towards manhood that centred around strength as expressed through rage. Cleaver was one of those who considered Jackson a martyr and was involved in his own gunfights with the police.

In an attempt to avoid prison, Cleaver fled to Cuba. There, he was able to spend more time considering his own perspective on manhood as it pertained particularly to Black men. The struggle for a Black male identity, he felt, is mostly internal. White society creates stereotypes about African Americans and then it is up to those Black men to either accept these assumptions or to create their own narratives.

There are conflicting messages at play here. On the one hand, Black males enjoy the privilege of being men. On the other, they experience deeply rooted societal oppression and mass incarceration, leading to justifiable pent-up rage. For Cleaver, though, the role of the man is to continually grow and evolve. This cannot be achieved through anger alone.

Reconstructing masculinity

In working-class, inner-city communities, hypermasculinity can often be seen as a sign of strength. And in some instances, this may lead to some males who may exhibit a personality that is destructive without accountability. This inevitably leads to lawlessness which results in incarceration, an early death, or both.

While in solitary confinement, however, Cleaver took a different approach. He began to reflect on the fact that the vast majority of prison inmates didn’t leave prison as improved men. Rather, they tended to live more violently than before. The common cycle for African American inmates was to go from prison to parole and back to prison, leaving no room for growth.

While reflecting from his prison cell, Cleaver began to restructure his manhood. He let his pride slip away, leaving something far more vulnerable. Having deconstructed his own identity, Cleaver started to rebuild it through his writing. Free from the demands of standing up to the racial injustice in his community, he was able to practice introspection and reflection, considering what being a man was truly about. Upon leaving prison, Cleaver joined the BPP, and eventually fled to Cuba after being involved in a shoot-out with police.

Returning to God

Keen to avoid the same fate as Jackson, which he believed was at least partly caused by Jackson’s perennial rage, Cleaver spent some time considering the meaning of life. Like many members of the BPP, he had adopted a broadly Marxist approach to religion, viewing it as a system of oppression by the white ruling class. However, on his journey of growth and evolution as a man, Cleaver returned to God.

Cleaver continued to live through a combination of Christian and Islamic beliefs that reinforced a peaceful, loving sense of manhood.

The parables and Bible quotes that Cleaver had remembered from his childhood helped him through the most difficult internal struggles. They enabled him to overcome much of the rage that was pent up inside him due to a lifetime of injustice. In the place of this rage came inner peace, and a new, vulnerable approach to manhood.

Cleaver’s rebirth as a Christian was not unanimously accepted, with many believing it to be a ploy to receive judicial leniency. However, for many young Black males, it created a new narrative of how to approach masculinity.

The road to spirituality was not entirely smooth for Cleaver. Catholicism still felt rooted in white dominance. It was hard for him to accept that God could allow such injustices to exist and he viewed evangelism as increasingly commercialised. Nonetheless, he continued to live through a combination of Christian and Islamic beliefs that reinforced a peaceful, loving sense of manhood; a masculinity that was kind and measured, not just to others, but to himself as a Black man.

Jackson and Cleaver both took their own distinct paths towards constructing their identity under difficult life circumstances. They both sought to find a solution to their manhood. Dying a martyr, Jackson expressed his masculinity in being defiant even in the face of death. This continues to resonate with Black activists, creating a space for social progress.

Cleaver lived a different life to Jackson, despite both being involved in a similar pursuit of manhood and identity. He showed that masculinity need not only be found through the barrel of a gun, while facing down an oppressor. It can be found while on your knees, in submission to something greater than yourself. Dr Jones concludes that when we observe the life of Eldridge Cleaver, we can explore how manhood can evolve and grow over a lifetime. Both men have proven the potential for others to forge their own paths and to redefine their own identities.

Personal Response

To what extent is the concept of rage important to the plight of African Americans?

<>I do not believe that rage is inherently important to any group of people; however, indignation in the face of injustice and systemic oppression is justly warranted. Cleaver and Jackson illustrate forcefully and eloquently the exasperation of inmates who are silenced by virtue of their real and imagined transgressions against humanity.