A butterfly’s point of view: Contest or sex recognition?

Contest behaviour has been studied in wildlife for many years. When animals compete, it is usually over limited resources such as mates, territory or food. Behavioural ecologists (those who study an animal’s behaviour from the point of view of Darwinian natural selection) have produced countless theories about why contests begin, why they end, and what leads to the winner. Contrary to these theories, butterflies have no weaponry and males exhibit unique mating patterns, either chasing flying females or crowding round pupae. In addition, the males also engage in chasing behaviour with other males. The researchers produced a series of theoretical, observational and experimental papers to investigate and understand butterfly behaviour. The main question they aimed to answer: “Are butterflies competing for territory when they give chase, or is their behaviour more a process of sex recognition to aid with courtship?”

Reproductive behaviour

Males of many butterfly species occupy a territory, with no benefit other than to access females. Once they see a flying object (whether it be a male or female butterfly, another insect, or a predator) males often fly over and “give chase.” If the opponent is a conspecific male, the two males chase each other. This behaviour was once thought to be contest behaviour, and the main game theory which stood out was the war of attrition model. However, butterfly contests conflict with the main assumptions of this model.

Game theory

Game theory is well established within multiple disciplines, including business studies and animal behaviour. In behavioural ecology, it decides which behaviours will become an Evolutionary Stable Strategy (ESS). ESS’s are the “strongest” behaviours which will be evident throughout the population. They cannot be “cheated” – i.e. outcompeted by other behaviours. There are various models which game theory helped to establish – one of them being the war of attrition.

War of attrition

War of Attrition states that animals will engage in costly displays (either direct combat or “warning” signals). These displays finish when the animals’ accumulated cost (such as energy depletion), reaches the threshold level. It is the loser’s Resource Holding Potential (RHP) that dictates the end of a contest. An animals RHP is its ability to “win” resources against their competitor; factors such as body size can aid this. The model has two main assumptions:

- Resting opponents can have costs inflicted upon them.

- Competitors can distinguish between rivals and others such as partners.

It was once thought that the chasing behaviour seen in butterflies was a war of attrition, however there is much conflicting evidence to this idea.

The conflicting evidence

By interrogating the literature, Dr Takeuchi discovered that the butterflies’ behaviour could be simplified to a model which required less cognitive ability on the butterflies’ behalf. Because the butterflies lack any weaponry (teeth, claws etc), it is unlikely that costs will be placed upon a resting opponent. However, some species of butterfly do engage in “clashes.” Despite this, neither butterfly ends up injured. Clashes are performed by two flying butterflies, meaning that a resting opponent is not having costs inflicted upon him. There is another potential cost: predation. However, it is more likely that the butterfly which is displaying is more likely to be predated on – either due to the increased movement alerting predators, or the depletion of energy making it harder to escape.

The butterflies also chase both sexes. Sex recognition abilities vary between species. Some butterflies can determine the sex of “pretend” butterflies from a distance, whilst others cannot. There have been no studies which show that males can discriminate from the sexes during aerial encounters. This may be because female butterflies lack strong sex pheromones, or because the poor vision of both the sexes, making it hard to discriminate from a distance.

Dr Takeuchi discovered that the butterflies’ behaviour could be simplified to a model which required less cognitive ability on the butterflies’ behalf.

The Erroneous Courtship Hypothesis

In 2016, Dr Takeuchi and his colleagues put forward an elegantly simple model: The Erroneous Courtship Hypothesis. Their model assumes that male butterflies seek to discover the sex and species of any flying object. They approach the object and begin to chase it. The chasing will either end in copulation or, failure. The pursuit will be classed as a failure either because the object is a male butterfly, or because it is a completely different species altogether. How long the male butterfly chases this object for depends on various factors such as the reproductive potential of the male, and the likelihood that the object is another female butterfly. So, the aerial clashes and chasing may in fact be a result of the erroneous courtship.

If the animal being pursued is a female butterfly and she is receptive, they will both alight and the male seeks copulation. The costs spent by males depends on factors such as their physical condition and energy levels. For example, males with less residual reproductive value will court females for longer (because they have less future chance), meaning the chase will be longer.

But, why does the butterfly flee the area when the chase has finished? Surely it must be better to wait in pursuit of another female? The butterflies’ cognitive abilities are not as intricate as many mammals. They find it difficult to distinguish between butterflies and other flying insects such as bees and wasps. When sexual recognition is complete and the chase is abandoned, it makes sense to escape the territory in case they are being preyed upon by a predator. Of course, if you have been consumed by someone else, you will have no more opportunities to pass on your genes.

The observations

In a recent publication, Dr Takeuchi tested the robustness of the erroneous courtship hypothesis by investigating the sex recognition abilities of the Old World swallowtail (Papilio machaon). The swallowtail is one of the most incompatible species with the hypothesis: male swallowtails perform a typical courtship flight to flying females (suggesting the ability of identifying flying females). In addition, males grab each other with their legs during the aerial contests over a mating territory (suggesting that they identify flying males and attack each other).

A census route was established in the study areas (called transects). Interactions between organisms which occurred within these transects were measured. Takeuchi recorded male versus male interactions, male and female interactions, and interactions with other species. They were recorded until either the interactions finished, or the organisms left the transect and could no longer be observed.

Dr Takeuchi shows us that it is sometimes best to think outside the box and critique the existing literature, to let you see things in a new light.

In another set of experiments within the study, he used butterflies reared in captivity. They were introduced to males and the behaviours of their interaction recorded. The males chased both females, males and other insects. However, the female chase is the only one that resulted in copulations. The interactions between butterflies (both male and females) lasted longer than the interactions between male butterflies and insects and butterflies of other species.

It was thought that chasing was a form of sex recognition – however, one copulation included no chasing as the female allowed copulation almost instantly. Furthermore, the male encounters lead to leg grabbing – which could be a form of territorial contest. Does this mean that this butterfly can distinguish between the sexes?

The experiment

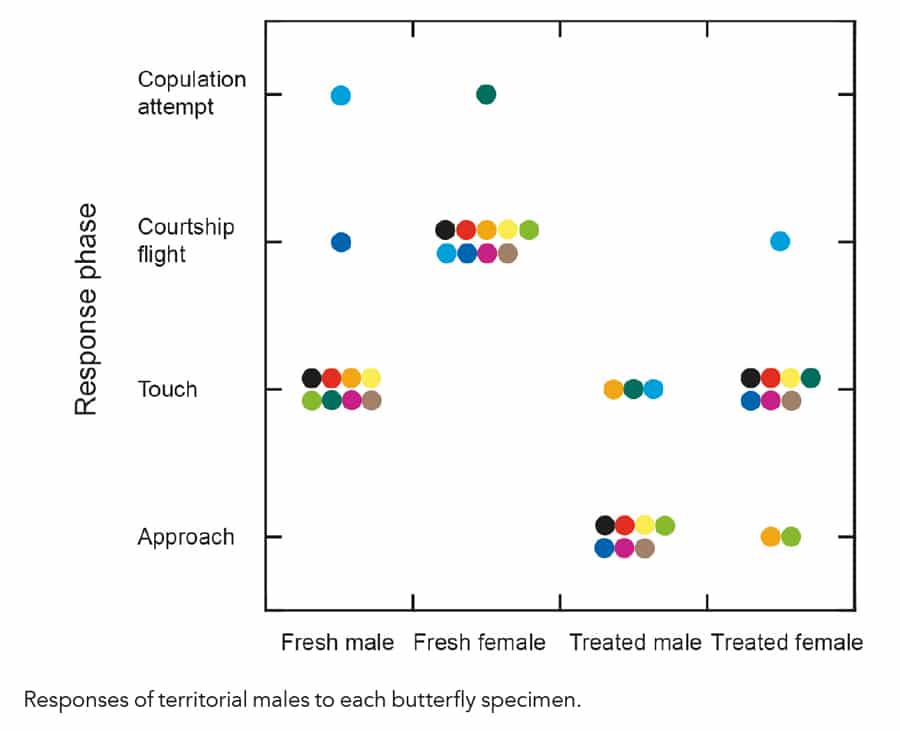

Could the swallowtail disprove the erroneous courtship model? Dr Takeuchi demonstrated that the swallowtails engage in what seems like territorial behaviours with other males, and courtship flights with the females. If male butterflies can identify the males from the females, the erroneous courtship hypothesis is no longer valid. The behaviour in males was measured and analysed against four different types of butterfly (Takeuchi et al., 2019)

- Fresh male; a specimen killed within 3 hours before the experiment.

- Fresh female; prepared the same.

- Treated male; a specimen soaked in chloroform for 24 h to remove chemicals, and then rinsed with fresh chloroform for 24 h.

- Treated female; prepared the same.

Males touched fresh female specimens with his legs, and showed typical courtship flight to them. For the other types of specimens, they rarely showed courtship flight although they approached and, in many cases, touched them. In addition, territorial males reacted longer to fresh males than to fresh females. These results indicate that although territorial males recognise flying females as sexual partners by sensing their chemicals, they cannot identify flying conspecific males, and continue to gather information on them.

In conclusion, males of the butterfly regarded conspecific males as something like a female. In natural male-male interactions, both males are likely to attempt to touch the opponent’s wings, which leads to leg grabbing. In this experiment, the erroneous courtship hypothesis cannot be disproved. This study shows that although a certain model may be applicable to most species, we cannot automatically assume the same is true for the whole Animal Kingdom. Dr Takeuchi shows us that it is sometimes best to think outside the box and critique the existing literature, to let you see things in a new light.

Personal Response

Do you think, in time, that different models will be suggested for most insect behaviour? Will it be difficult to prove or disprove any new theories?

<>Do you mean that insect behaviour will be described in different manner compared to other animals such as vertebrates? I think so, in some cases. Our interpretation of animal behaviour tends to be influenced by our intuition. I think behavioural ecologists should pay more attention to the constraints in the abilities of animals, and models should be constructed based on these constraints. We will be able to choose better models that are based on simpler assumptions and fit real animal behaviour.