Disruptive change in contemporary medical education:

Unintended consequences and risks

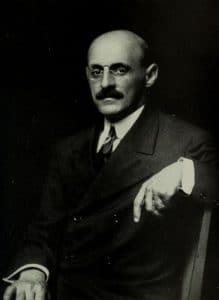

Enthusiasm for reform needs to be tempered by a more cautious and realistic approach to avoid unintended consequences.” This is the take-home message from Professor L. Maximilian Buja, a world-renowned clinical and academic pathologist, physician scientist and medical educator. The arguments for his position are set out in a recent publication in BMC Medical Education. They are forcefully put, unapologetic and uncompromising in the starkness of the reality they describe and, many would say, difficult to disagree with.

Professor Buja’s position is that the overarching goal of medical education is the imparting of the highest principles, knowledge and skills, not bending medical education to follow prevalent but counterproductive personal and cultural trends. By way of context, the University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston restructured its undergraduate medical curriculum in 2013 and instituted it in 2016. Professor Buja was Dean of the Medical School from 1996 – 2003 and remains closely involved in both undergraduate and postgraduate education.

The new integrated curricula being developed across the United States, and indeed across much of the developed world, have as their core objective the production of physicians “fit for the twenty-first century.” The emphasis is on developing skills in modern clinical reasoning and decision-making. At the same time the delivery of teaching has seen a move away from the role of the teacher as purely an information provider and towards that of a learning facilitator, the point being (as per Harden and Crosby, 2000) that the role of the teacher is “not to inform the students but to encourage and facilitate them to learn for themselves using the problem as a focus for the learning.”

Whereas there is merit in parts of the new curricula, they are not without their difficulties, or their critics. There is a risk, now being articulated with increasing frequency, that they will produce graduates (i.e. doctors) who do not have the level of clinical expertise expected of them because they do not have a grounding in biomedical science or an understanding of the pathological basis of disease. There is a worry that the new generation of physicians will become indistinguishable from other healthcare professionals at a time when those characteristics which set them apart should be ever more important.

The new curricula have been described as fitting the definition of “disruptive innovation,” a term which describes a process by which a product or service takes root initially in simple applications at the bottom of a market and then relentlessly moves up market, eventually displacing established competitors. Whereas innovation is generally perceived as being good or making improvements, the fear being expressed is that there is a downside to disruptive innovation in the context of medical education with unintended and potentially detrimental long-term outcomes for academic medicine and clinical practice, and those fears cannot be ignored.

MEDICAL EDUCATION: PAST AND PRESENT

Throughout the past century medical education has remained faithful to the principles of William Osler and Abraham Flexner. Osler championed bedside (clinical) teaching, which brought students into direct contact with patients, whilst Flexner (a generation later) recommended that medical schools be university based with minimum admission criteria and a rigorous curriculum. The result was the two-pillar model of medical education with basic medical sciences and the clinical sciences. This is the model Professor Buja argues successfully produced generations of “scientifically grounded physicians capable of a high level of clinical practice as well as a subset of physician-scientists and academicians.”

In the modern era the delivery of medical teaching is influenced and possibly compromised by commerce. One of the issues said to affect undergraduate and graduate medical education is the fact that much of the teaching takes place in academic health centres, which must function in the real world of healthcare delivery and which are (in the United States at least) subject to market forces. Advances in medical care and technology have been the driving forces behind the curriculum changes, which are in part a response to the need to produce a new type of physician more attuned to and equipped for practice in the current healthcare scene.

RE-ENGINEERING THE CURRICULUM

There has been a push in recent years for undergraduates to demonstrate “competencies” rather than cognitive knowledge. This educational approach works by identifying specific things someone needs to be able to do in order to pass a course, or a stage in a course, and allows the student to move forward as soon as they have demonstrated that they have reached the expectation. In medical education the goal now is to produce “competent” physicians. That they should be competent is unarguable but that should not be the end point, which must surely be to produce excellent, well-rounded and fully grounded physicians, set apart from their contemporaries in other healthcare professions. In that context the competence-based curriculum would fall short of producing ideal outcomes. It is “short-sighted, philosophically questionable, methodologically complex and highly controversial.”

It is counterproductive to dilute the learning experience of the core material in the pre-clinical years.

In pursuit of the new curriculum, a variety of learning approaches have been introduced, including small group sessions, problem-based learning, self-directed learning and team-based learning. The lecturer is now the learning facilitator. In addition, whilst looking at the pedagogical approach to medical education, curriculum designers looked at the same time at the content, with a view to reforming that as well, in order to develop the requisite skillset in future clinicians.

What has emerged from the redesign process is a fully integrated curriculum which does away with the distinction between the critically important pre-clinical (basic medical sciences) two-year period and the apprenticeship-like clinical two-year period. It brings in additional content called Health Systems Science, as a co-equal to basic and clinical sciences, to cover topics from population health to interdisciplinary care. The justification is that tomorrow’s physicians need broader skills and knowledge than previous generations, but it fails to account for the fact that teaching time is finite, or it advocates addressing this by repealing the major part of the basic sciences curriculum in order to make time and space for students to develop skills in modern clinical reasoning and decision-making. The thinking is that Health Systems Science topics should take precedence over basic medical science because they are more relevant to the modern landscape and, in any event, there is a great deal of overlap and repetition in basic science teaching.

THE DOWNSIDE OF INNOVATION

Professor Buja is not opposed to integration of the curriculum but argues that there are more effective ways to achieve that objective without sacrificing the foundations of a good medical education. He reminds us that the first two years of the undergraduate medical education (UME) curriculum is the only time in the professional career of a physician that the fundamentals of biomedical science and the clinical skills of history taking and physical examination intersect. Furthermore, studies have repeatedly shown that factual knowledge of medical science is essential for the development of clinical skills.

What this means is that you cannot simply dispense with basic medical science teaching to make way for Health Systems Science teaching without having an effect on the calibre of the physician produced. As Professor Buja explains: “It is counterproductive to dilute the learning experience of the core material in the pre-clinical years by substituting other topics that are best learned after a foundation is laid.”

from summative assessment by grades in some medical schools and a move towards a simple pass/fail system based on competency. As a knock-on effect, this artificially inflates the importance of United States Medical Licensing Exam (USMLE) Step 1, as the sole objective evaluator of medical students’ cognitive achievement. The residency programs, already hugely competitive, now almost always ask applicants to disclose their Step 1 score. In an environment where the medical schools are not offering their own meaningful summative assessment, what has developed is a fundamental alteration of the preclinical years and how students relate to it, creating a “Step 1 climate” which impacts negatively on student wellbeing.

Enthusiasm for reform needs to be tempered by a more cautious and realistic approach to avoid unintended consequences.

Professor Buja is quite clear on this point: “the dilemmas about the “USMLE issue” can be diffused by a return to providing meaningful grades for medical school courses and an overall summative evaluation for the four years of medical school”.

THE IMPACT ON PATHOLOGY

Pathology is both a medical science and a clinical discipline. It links basic biomedical science to clinical medicine, and provides an understanding of the pathological basis of disease. It is unquestionable that reducing teaching in pathology will have a significant onward effect on a physician’s clinical acumen and expertise, but this is what is happening under the newly designed curriculum. Pathology courses have been discontinued, teaching on the methods and importance of autopsy (“a uniquely important procedure for quality assurance in medicine”) has all but stopped, and the task of grounding medical students in the pathogenesis and pathophysiology of disease has been made considerably more difficult. Added to this is the fact that fewer graduates are applying for pathology residencies than ever before; those who do take up positions are having to be sent on “boot-camps” to provide them with the basics of a necessary foundation in pathology-specific medical science.

In the same way, physician scientists stand at the crossroads of basic science and clinical medicine. Their numbers are small and are, sadly, diminishing because of the diminished position of basic science in the new curriculum.

THE CAUSE AND THE CURE

With the concerns about the direction of medical education under the new curriculum comes a resistance to the idea that modern healthcare delivery has rendered the traditional curriculum obsolete. Those in favour of keeping or reverting to the traditional system contend that moving to the new curriculum means fatally undermining the integrity and usefulness of the old. For something to win, something has to lose. Secondly, the new curriculum requires an enormous increase in faculty staff in order to deliver the format in smaller groups than, say, a lecture theatre-sized group. Thirdly, the new holistic, integrated approach is perhaps not quite as amenable as it might have appeared, as it has been shown to create tension between that approach and the need to prepare for USMLE Step 1.

Professor Buja is certain that the way forward is the repositioning of medical science in the medical education curriculum to reflect its unchanging and continued importance. This would require the provision of protected time, free from the threat of takeover by other competing academic priorities and the restoration of subject-based foundational courses. These could be combined.

He reiterates that his observations and his contribution to the debate around medical education should not be interpreted as objecting to integration within the curriculum. He does not foresee a need to downgrade the Health Systems Science teaching, insisting that there are ways to integrate its content over the course of four years. Extending the same approach to basic sciences would therefore come with the expectation that there should not be a downgrading of the foundational science component of the medical school curriculum.

What this would mean in practice is that medical schools should commit to maintaining the integrity and cohesion of the foundational disciplines (anatomy, physiology, biochemistry, pharmacology, microbiology and pathology). Close coordination of these subject-based courses, particularly in the first year as in the McMaster University Medical School model, gives great scope to learn related subject matter contemporaneously while at the same time relating the foundational to the applied with integrating components such as small group problem-based learning sessions.

Personal Response

You have a long and distinguished career in clinical and academic pathology. Given the indications that enthusiasm for the discipline is not as strong as previously, what would you do to increase its appeal to the modern medical school graduate?

<>I am committed to proactive personal advocacy for academic pathology, a cause I am passionate about. I have taken to devoting a portion of each classroom session with medical students to my practice of pathology showing with actual cases how pathology can yield diagnoses of major importance in the care of patients. I also point out how correlation of clinical and pathological features of a case can yield information and ideas to generate new knowledge which is the goal of research. I also conduct an increasingly popular and well attended monthly cardiovascular pathology conference for our Center for Advanced Cardiopulmonary Therapies and Transplantation where I show how our pathology studies have contributed to the unravelling of the cause of patients’ problems and how our studies contribute to their care. I strive to be a role model of a physician-scientist engaged in research, teaching and clinical service with a focus on cardiovascular disease and pathology.