Establishing a new care pathway for deep vein thrombosis

Dr Tony Wan of St Paul’s Hospital in Vancouver identified a gap in the treatment pathway of deep vein thrombosis (DVT), causing repeat visits to the emergency department (ED) and putting pressure on a department that is already prone to overcrowding. The new care pathway saw the expansion of St Paul’s Hospital Thrombosis Clinic, where patients are referred directly after obtaining an ultrasound diagnosis. This led to fewer ED visits and a reduced wait time for patients.

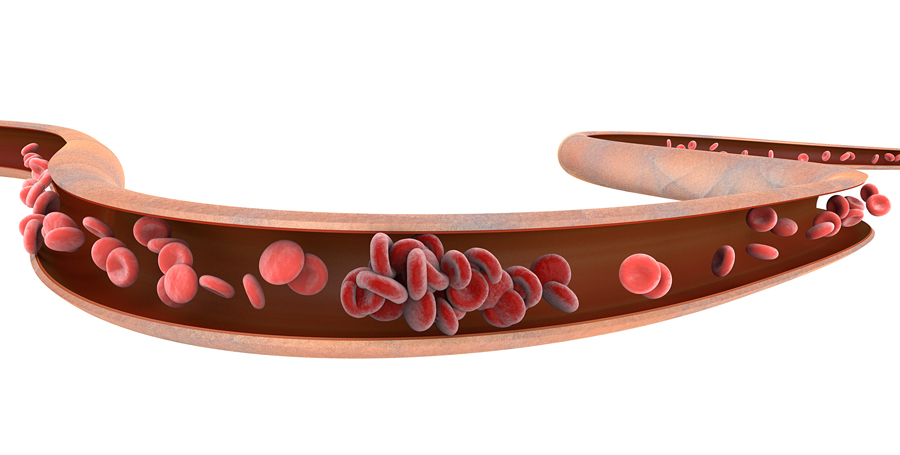

Deep vein thrombosis (DVT) occurs when there is a blood clot in a deep vein – a vein that is located deep in the body. This condition usually occurs in the legs. DVT requires urgent care and treatment because it may lead to life-threatening complications, such as pulmonary embolism, which is when a blood clot in the legs breaks away and travels to the lungs. This causes difficulty breathing, coughing up blood, chest pain and, in severe cases, death. Untreated DVT and subsequent untreated pulmonary embolism are associated with a mortality rate of 25% in three weeks. A blood clot in the lungs can prevent normal blood flow in the lungs, causing damage to other organs due to a lack of oxygen-rich blood. Therefore, rapid diagnosis and treatment, such as anticoagulants (blood thinners), are urgently needed.

Traditional DVT treatment pathway

Like in many other hospitals, patients suspected with DVT at St Paul’s Hospital in Vancouver, Canada, are directed to the ultrasound department to visualise the blood vessels. Once a confirmed diagnosis of DVT is obtained, patients are then directed to the emergency department (ED) for urgent treatment. At St Paul’s Hospital, there were 383 patients who visited the ED to treat DVT between 1 February 2017 and 31 January 2019. Of the 383 patients, 355 patients did not require hospital admission and received outpatient treatment at home. A 2014 study by Lozano et al found that patients who seek treatment in hospital and at home had comparable outcomes, such as similar rate of blood clot recurrences.

However, 159 DVT patients at St Paul’s Hospital during that period required repeat ED visits within 30 days. A possible explanation is that the necessary diagnostic investigations and medical treatment to successfully manage DVT are not readily accessible in the outpatient clinic, so patients are then directed to the ED instead. For example, there may be inadequate resources to accurately assess newly diagnosed patients, such as the inability to quickly arrange urgent laboratory tests or further ultrasound imaging, and physicians that are inexperienced with DVT.

DVT requires urgent care and treatment because it may lead to life-threatening complications, such as pulmonary embolism.

Another weakness in the care pathway for DVT is that patients are directed to the ED because it was the only department available to treat patients and follow up on critical testing results. Family physicians in primary care who had requested the urgent ultrasound were either unavailable to reassess the patient urgently, unavailable to obtain other urgent laboratory test results, unable to access anticoagulants, or preferred to have a specialist initiate the anticoagulant. Therefore, the ultrasound department could only send DVT patients to the ED.

Moreover, the ultrasound department had limited operations in the evening. Suspected patients who visited the ED after hours would require a second visit the following morning after an ultrasound diagnosis was confirmed to assess the ultrasound results. Therefore, this left patients with long waiting times of over two days.

Improving the DVT pathway

To minimise the burden on ED, Dr Tony Wan from St Paul’s Hospital Thrombosis Clinic in Vancouver has developed a standardised clinical pathway to immediately direct newly diagnosed patients with DVT from the ED and ultrasound department to the thrombosis clinic, with the aim of preventing overcrowding of the ED and minimising waiting time for patients. The staff capacity in the thrombosis clinic was increased to anticipate the growing number of patient visits, such as the hiring of full-time nursing staff. Dr Wan aimed to reduce the number of ED visits for patients diagnosed with DVT by 25% within a year of introducing the new pathway care for DVT at St Paul’s Hospital.

Information sessions were held for healthcare professionals involved in the ED and ultrasound department to fully understand the newly implemented DVT treatment pathway and the value of the thrombosis clinic. St Paul’s Hospital started using an electronic medical record system in November 2019.

After the implementation of the new DVT pathway, from February 2019 to January 2020, the number of ED visits for DVT was 106, with an average of 8.8 visits per month. Compared to the average of 16 ED visits per month during the period of February 2017 to January 2019, this meant a 50% reduction in number of ED visits.

During the same time span, from February 2019 to January 2020, 162 patients visited the thrombosis clinic with an urgent referral. 67 of these patients did not visit the ED because they were referred directly from the ultrasound department immediately after the diagnosis. The other 95 patients accessed the ED after hours, but the ultrasound department lacked an ultrasound sonographer, so patients had to wait for an ultrasound appointment and a visit to the thrombosis clinic the following morning.

Previously, these patients had to visit the ED more than once. With the implementation of this new treatment pathway, patients are now assessed in the thrombosis clinic with virtually zero wait time. Collaboration with primary care providers is needed to identify reasons for sending patients suspected of DVT to ED first instead of directly to the ultrasound department to obtain a diagnosis. By sending patients directly to the ultrasound department, a visit to the ED, especially during after hours, and subsequent discharge of patients from the ED and return to the hospital to attend an ultrasound appointment the following day, could be avoided.

This new treatment pathway meant a 50% reduction in the number of ED visits.

The number of patients who required a repeat visit to the ED within 30 days also decreased from 41.5% to 10.4%. Further experiments are needed to identify the reasons for more ED visits, either directly related to the management of DVT or other unrelated medical issues.

The number of patients who were admitted into the hospital and the length of ED stay were relatively constant, from 7.3% to 8.5% and 4.1 hours to 4.4 hours, respectively. Therefore, the new DVT treatment pathway did not introduce significant changes to the system and was not detriment to the patient journey. Investigations of the reasons for hospitalisation can potentially identify strategies to reduce hospital length of stay or prevent future hospitalisations.

In conclusion, Dr Wan was able to reduce the number of visits to the ED related to DVT, thereby reducing ED overcrowding. Patients can then receive the timely care they need, not only for DVT but for other conditions. Learnings from the implementation of this pathway can be used in other hospitals that possess the resources to set up a thrombosis clinic.

Personal Response

What improvements can be made to the thrombosis clinic to further reduce the number of patients visiting the ED?

The next step is to build a stronger connection between the thrombosis clinic and the primary care physicians working in the clinics near St Paul’s Hospital. Ideally, the primary care physicians will send patients to the thrombosis clinic directly, instead of the ED, when there is a concern for DVT. The thrombosis clinic will need to be readily accessible to the primary care physicians and their patients. Communication is the key.