Geopolitics of the illicit global economy

‘Black spots’ are the safe havens that offer a base of operations for transnational criminal, insurgent, and terrorist organisations. At the Maxwell School of Citizenship and Public Affairs of Syracuse University, USA, Professors Stuart Brown and Margaret Hermann are attempting to shed greater light on these geopolitical places by looking at the intra-regional, cross-national, and international linkages among them. Their work has led them to ask a series of questions concerning what black spot networks reveal about the governance and financing of the illicit global economy, why those operating in black spots resemble multinational corporations, and what this means for national and international law enforcement.

Most of us know the world map that shows internationally recognised country borders. But Professors Stuart Brown and Margaret Hermann are seeking a new map, one that shows the places across the globe from which transnational criminal, insurgent, and terrorist organisations operate and which they appear to govern. Like the black holes in astronomy that defy the laws of physics, these black spots function outside our Westphalian state system.

Black spots and illicit activities

Black spots are places that enable the illicit activities of transnational criminal, insurgent, and terrorist groups, facilitating them trafficking in drugs, weapons, people, money, natural resources, household goods, and violence. Brown and Hermann’s Mapping Global Insecurity Project has so far identified 150 black spots around the globe and completed in-depth case studies of 80. They sought to identify what characteristics of these geographic spaces make them so attractive to illegal actors, and to understand how these locations are linked.

Blue Planet Studio/Shutterstock.com

In doing so, the researchers had to rethink notions of sovereignty and the global economy, and to face some of the challenges that confront authorities trying to understand how these illegal actors see the world and conduct their business within it.

These modern-day versions of 18th-century pirate islands do not sit apart from our world order – some 3–5% of global GDP is estimated to come from illicit activity – nor, as the researchers discovered, are they ungoverned. In fact, Brown and Hermann found that all 80 black spots studied had rules and norms in place to guide people’s behaviour and to facilitate keeping them out of sight of national and international law enforcement and the media.

The illicit organisations operating in black spots are not dissimilar to multinational corporations. Both are non-state actors; both are driven by profit maximisation.

Black spot characteristics

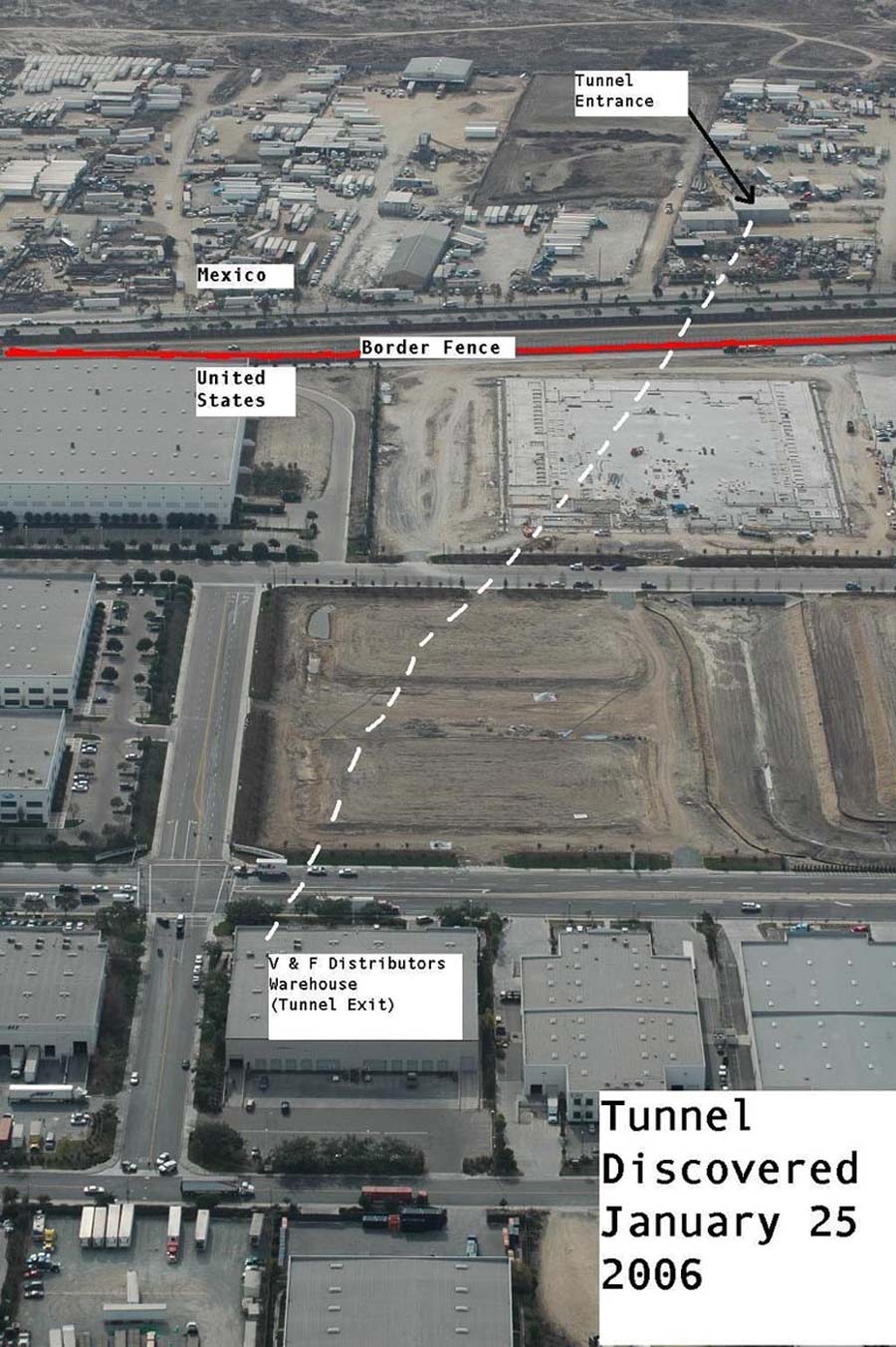

Black spots come in a spectrum of sizes, from single neighbourhoods to whole provinces; however, 90% are found along national borders, often in regions that are jurisdictionally challenging (eg, disputed, porous, and/or poorly defined borders). Three quarters are in challenging terrain (eg, mountains, deserts, and jungles). Around three-quarters are also along old, traditional trading routes like the ‘Silk Road’, and 86% are near conflict zones with ethnically heterogeneous populations. A large proportion are in ‘weak’ but not ‘failed’ states that offer some level of ‘services’ – infrastructure, a financial system – but with weak legal and governance systems. Most provide road, air, and water access to markets.

Contrary to expectation, Brown and Hermann found that black spots are not a post-Cold War phenomenon; more than half existed before 1991. Of these older places, many are in regions where national borders were drawn through the lands of ethnic groups, causing jurisdictional barriers that have given rise to insurgency and illicit cross-border activity. One example is the Durand Line, drawn by the British in the late 1800s to separate Pakistan and Afghanistan, which cuts through and divides the Pashtun tribal areas.

A new economic geography?

Brown and Hermann have recognised that black spots depend on one another to be economically viable. By mapping the flows of goods and money and identifying which illicit activities move in and out of which black spot, they can begin to reveal relationships among the black spots and to build a picture of the illicit economy. As this mapping exercise has evolved, the researchers have asked whether it is possible to identify how important a particular item is to a black spot’s economy, and how that might be monitored. In effect, what happens to these flows when national and international law enforcement intervene in an attempt to disrupt one part of an interlinked network?

With multiple illicit activities, those operating black spots can shift their focus to a different ‘trade’ when markets are interrupted.

For around three-quarters of the black spots studied to date, trafficking in drugs and conventional weapons are dominant activities. More than half are also involved in people trafficking and 37% are engaged in identifiable money-laundering activities. Indeed, the average number of illicit activities per black spot is four. With multiple illicit activities, those operating the black spots can adapt their activities to respond to changes in the markets for these items, shifting their focus to a different ‘trade’ when labour, materials, transport routes, or markets are interrupted, including by international law-enforcement efforts. In this sense, the illicit organisations operating in black spots are not dissimilar to multinational corporations. Both are non-state actors; both are driven by profit maximisation; and both use the advantages afforded by globalisation and communication technologies: namely the availability of labour, raw materials, product production, and transportation. Both also rely on redundancies and structures to mitigate market fluctuations and shocks: multinational companies on national/international regulations and the use of sub-contractors; the illicit organisations in black spots on bribes, protection money, legal front companies, and the support of local populations (achieved by fear and/or by improving quality of life and offering services not provided by the state).

Black spots are less ‘wild west’ than one might imagine – they tend to be organised around clear rules, norms, and structures.

Identifying the puppet masters

In terms of governance, black spots are less ‘wild west’ than one might imagine. In fact, they tend to be organised around clear rules, norms, and structures. Some of these are imposed but more often they are embedded in the black spot. An example of note involves the tribal areas along the border between Pakistan and Afghanistan. This region is beyond the effective control of either national government, but nonetheless operates under a clear structure that allows local leaders to trade in drugs, weapons, and natural resources. In this case, organisations like the Taliban are able to exploit multiple socio-geographical factors to their advantage, including poverty, rampant corruption, nearby conflict zones, and challenging terrain. Of the 80 black spots studied, 41% are controlled by insurgent groups, for example the Uighurs in China; 31% by terrorist organisations like al-Shabaab in Somalia; and 28% by transnational criminal organisations such as the Sinaloa Cartel in Mexico.

The Robin Hood curse

This research clearly shows that insurgent, terrorist, and transnational criminal organisations seek to base their operations in places with efficient market access and where they have authority, can control security, and can offer some stability to local residents. This results in the ‘Robin Hood curse’ – once established, removing a black spot deprives the local population of their livelihoods.

Tackling black spots requires a holistic approach. To date, however, governments have tended to focus on one activity at a time when addressing criminal activity. Moreover, global illegal networks move with the times and, without the rigid constraints imposed by the rule of law, can do so more fluidly than other entities. Staying on top of these changes is a critical step in tackling the global illicit economy, and one for which Professors Brown and Hermann are in the vanguard.

Personal Response

What are the next steps for the Mapping Global Insecurity Project?

Although with 80 black spots we cannot yet map the global illicit economy, we can theorise about how links could come into play with the black spots that we have studied in-depth to date. Along the borders of Macedonia, Kosovo, and Serbia as well as the borders of Bosnia-Herzegovina, Montenegro, and Serbia, there are communities that form part of the Balkan Route for the smuggling of drugs, weapons, and people headed toward Central and Western Europe. Most of these areas have high unemployment and smuggling is a way of life – it’s the easy and normal thing to do. And our ability to trace goods being trafficked into and out of Turkey at the beginning of the Balkan Route suggests the possibility of eventually identifying the network of black spots that a particular commodity follows as it heads toward Europe. In the process we have discovered a number of geopolitical hubs that produce, transit, and distribute illicit goods as well as engage in a wide range of illicit activities. Some represent ethnic enclaves that are seeking autonomy as well as the right to control and govern a particular piece of territory, such as the Hezbollah Territory, South Ossetia, and Azad Kashmir. Then there are the hubs that are found in prime geographical locations for trade and commerce and have been black markets for decades, if not centuries – for example, Kashgar, China; Ciudad del Este, Paraguay; and Dubai, United Arab Emirates. As the reader can see, we are beginning to have the routes and nodes for a map, if not the whole map quite yet.