Nesta: Collective intelligence, people-powered results and experimentation

Nesta is an innovation foundation aiming to turn bold ideas into reality and change lives for the better. Tackling problems with a combination of expertise, skills and funding, Nesta takes a practical, collaborative and evidence-based approach to the challenges faced by organisations on the frontiers of healthcare, over-stretched public services and in a fast-changing job market.

In these interviews with Aleks Berditchevskaia (Senior Researcher, Centre for Collective Intelligence Design), Daniel Farag (Director of Nesta’s Health Lab) and Albert Bravo-Biosca (Director, Innovation Growth Lab), Research Outreach found out more about some of the foundation’s initiatives and areas of interest, including collective intelligence (the combination of artificial and human intelligence), how people-powered results can disrupt health systems (and help regain people’s confidence in them) and the importance of bringing European agencies together through experimentation, as well as how experimentation and being mission-led is the best way of innovating.

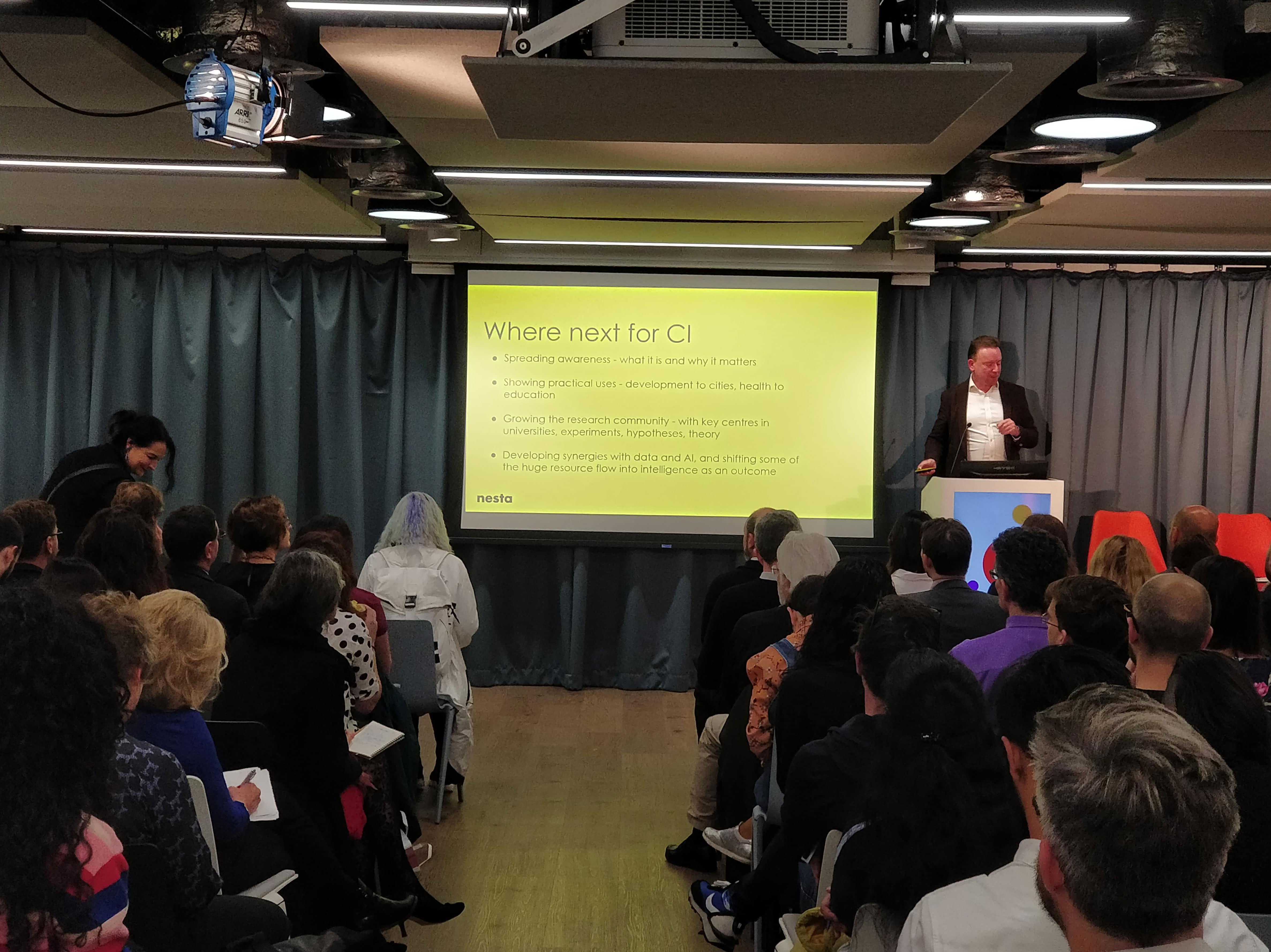

Hi Aleks! What problems are being addressed with collective intelligence, and how?

All manner of problems, big and small, can be addressed with collective intelligence. We think they fall into four main categories: understanding problems, seeking solutions, making decisions and learning and adapting.

When there is a lack of information about how an issue is unfolding in real-time, for example during environmental emergencies, collective intelligence can be used to actively solicit information from citizens on the ground or by aggregating their social media postings – e.g. Petabencana, an Indonesian platform, which creates a dynamic map of flooding reported by citizens, helping authorities to plan and prioritise response. Collective intelligence is also being used in deliberative democracy to help make decisions about legislation, e.g. the participatory process called ‘vTaiwan’ followed by the Taiwanese government, or to generate new ideas and prioritise public spending through participatory budgeting, like Idee.Paris.

We have developed a framework for the four types of challenges that you might want to solve with collective intelligence.

When it comes to some of the big challenges that we’re facing in society…the old ways of solving problems don’t seem

to be working.

What are the key challenges associated with successfully designing collective intelligence?

One of the core principles of collective intelligence is the diversity of inputs, meaning cognitive diversity as well as demographic traits. Achieving this is not easy. There are also challenges associated with particular methodological approaches and the goal you’re trying to achieve. For example, collective intelligence based on ‘wisdom of crowds’ aggregation typically relies on independent contributions from all participants, which can be hard to guarantee. But when it comes to problem-solving in groups, it is important that all participants are able to contribute any unique expertise they have and this requires minimising the occurrence of pervasive social biases that can sometimes lead to unsubstantiated privileging of certain voices over others. There are also challenges associated with scale, for example, synthesising tens of thousands of inputs generated by citizens during deliberative democracy activities (such as the Grand Debats in France), and sustaining participation over long periods.

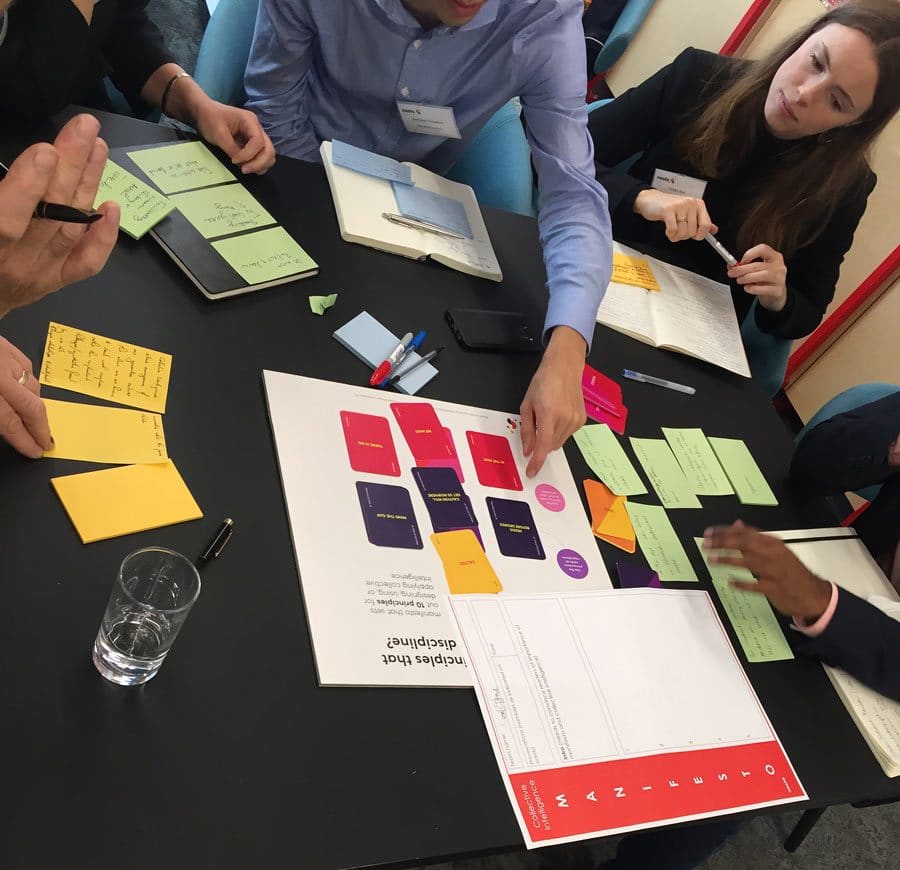

How do Nesta’s toolkits and guides help simplify the process of designing collective intelligence?

The Collective Intelligence Design Playbook is our first attempt at translating what we know from academic research in the field, existing innovation and design methods into a step-by-step guide for those interested in designing collective intelligence projects. We break it down into the different stages of design, from defining a problem to the final change that you want to see as a result. There are prompt cards, activities and tips for facilitation at every stage to make sure that anyone is able to answer the design questions, no matter their level of experience with collective intelligence. We’ve included more than 50 examples of different methods in action using real-world case studies; this really helps to spark the imagination of users and demonstrates the relevance of the methods. We hope it can help others start their journey into discovering collective intelligence and its potential.

Tell us about the emerging findings from your collective intelligence experiment.

Throughout 2019, we’ve been running an online crowd predictions experiment to test how well the wisdom of crowds principle holds under the conditions of extreme uncertainty caused by Brexit. Twice we asked about the likelihood of Article 50 being extended, and the crowd consensus (the aggregate of all individual forecasts) assigned the highest probability to the correct answer. The same was true for our questions about the outcomes of elections, both in the latest UK General Election and the European Parliament Elections held in 2019.

We’re still working on the analysis of the more recent questions and probing deeper into the effects of factors such as gender, age and location. We’re also interested in the patterns of participation and how they changed over the course of the project.

What important implications does this project have for our future society?

When it comes to some of the big challenges that we’re facing in society, such as climate change, health and social inequality, economic and environmental migration, the old ways of solving problems don’t seem to be working. In some cases the problems are entirely new, in others, the dynamics that affect their development are changing. Emerging technologies, most recently artificial intelligence, are often touted as potential solutions, but the truth is that without large-scale behavioural change or a better understanding of the ways these issues are affecting people on the ground it will be difficult to make progress on such multi-factorial, complex problems. Collective intelligence combines these complementary capabilities, drawing on human intelligence at scale and with the help of technology to solve problems. It offers a whole suite of methods ranging from crowdsourcing and citizen science to Challenge Prizes and crowd forecasting; it’s a great toolbox to draw on. We still have a lot to learn about how to optimise the design process, but it’s an exciting prospect.

Hi Daniel! Can you tell us about the importance of the work that the People Powered Results team is doing?

The People Powered Results team at Nesta are pioneering new approaches to achieving change and innovation in complex systems that are smarter, faster, more collaborative and more inclusive of citizens and the front line.

Public services are faced by a significant challenge, with many already struggling to meet rising demand and expectations on services changing at a frenetic pace. Those charged with transforming systems have found themselves stuck trying to ‘transform’ and at times spend their time wading through stubborn and sticky problems for a number of years. Despite best efforts, hospitals remain at breaking point, and not just in the winter, and social care seems to be in perennial crisis. The Nesta People Powered Results team recognised that many attempts to transform the system were missing a trick.

Front-line practitioners and people who use public services have unrivalled expertise in how the system and community operates, but often have little influence or ownership over change. Our approach empowers and connects those closest to delivery in order to drive change.

Empowering those on the front line to work alongside communities in new ways not only brings a renewed energy and power for change across a system but also yields a detailed level of insight into the real issues and challenges that are faced by a system to inform longer-term strategic ambitions and plans. We think a place-based, people-focused, rapid approach to change has been a missing part of the jigsaw in complex system change, and a reason why top-down reform on its own often fails to achieve its potential.

What is the 100 Day Challenge?

The 100 Day Challenge is a structured innovation process, combined with coaching support. The approach enables frontline staff from multiple organisations across a system to collaborate and rapidly experiment with new ways of working, to achieve real results for people and communities.

Public services are faced by a significant challenge, with many already struggling to meet rising demand and expectations.

The method complements traditional top-down approaches to change. It works with leaders of a system to mobilise those closest to the action-driving change from the bottom up, in real-time and at pace. 100 Day Challenges are intensive periods of action and collaboration that typically involve representatives from health, social care and voluntary organisations. System and organisational leaders are supported to break down longer-term strategies into challenges with measurable objectives. Frontline practitioners and citizens set ambitious goals and develop and test creative solutions in real conditions.

How can People Powered Results help the health system regain people’s trust?

Over the last five years, the Nesta team have worked in over 30 places across the UK to develop the approach, working alongside local leaders frontline staff and communities to achieve dramatic shifts in culture, performance and capabilities of the system to better deal with the sticky challenges they face.

In Stockton-on-Tees, the ‘Home Safe, Sooner’ initiative was designed and led by frontline staff from the University Hospital of North Tees. It is an integrated and personalised approach to hospital discharging and led to a 35% drop in delayed discharges and savings of £900,000 from 2017 to 2018 based on the clinical commissioning group’s data. It was named best integration project at the North East, Cumbria and Yorkshire and Humber Commissioning Awards.

In Tameside, cross-system teams took on the challenge of working differently with people at risk of diabetes. Within a short space of time and through adopting a community development approach giving people personalised information and support, 49% of people within their neighbourhood was no longer classed as pre-diabetic. People had achieved an average waist measurement reduction of 6cm, and an average two-level increase in self-reported wellbeing on the clinically validated Warwick Edinburgh scale. Following the challenge, teams have continued to support people at risk of diabetes and also used the engagement techniques to successfully reach other groups including people with chronic cardio obstructive pulmonary disease and people who are clinically obese.

To create a performance culture that is positive, collaborative, motivating and effective, the NHS needs to turn leadership on its head and build from the frontline up. What NHS staff need is permission to create and test new ways of working and the support of senior leaders to follow through. The results will not only improve key system metrics like hospital discharge but create a resilient culture of innovation that’s essential to meeting the challenges buffeting the NHS and their partners now and into the future.

Such a concept starts to put the public back into the

heart of public services by making its future a shared endeavour rather than the preserve of experts.

In what ways are you challenging the idea that leadership only exists at the top of the pyramid?

Much of the approach is inspired by the work of Ronald Heifitz and the theory and practice of Adaptive Leadership. This is not a new concept for the NHS or public services but one that can be difficult to put into action as it plays with the power dynamics within hierarchical systems. One of the main tenets of the theory and the work of the People Powered Results team is to distinguish between Authority and Leadership. Both are dependant on context, but the hard part is helping those in a position of authority – i.e. those with a job title, budget responsibility, etc. – to create the conditions for anyone to step into an act of leadership and contribute their ideas, expertise and ultimately take control of how change happens regardless of job title… but it’s not impossible if you can help people focus and take action and unleash their creativity.

Such a concept starts to put the public back into the heart of public services by making its future a shared endeavour rather than the preserve of experts and those in positions of authority.

How can addressing leadership lead to innovation?

Methods like the 100 Day Challenge offer a glimpse of what is possible when you rethink the role of leaders of public services as capability builders, and choreographers of social change tasked with untapping the creativity, energy and innovative potential within their staff and communities. However, for many leaders, this is a world away from their day-to-day as they are plagued with the constant distractions of traditional change approaches that tend to focus on finding ways to hit the target, but miss the point!

Hi Albert! How would you define experimentation and mission-oriented innovation?

Often when policymakers talk about experimenting they mean ‘trying something new’. But this is not enough. An experiment is a test and, therefore, it requires putting in place the systems and processes to learn whether the intervention is actually working or not.

Mission-driven innovation policies are a concerted, cross-sector effort mobilising large resources with a clear goal in mind. The classic example is the moonshot. Yet, despite all this talk about missions, there is still very little knowledge, practical guidance and prior experience on how to successfully implement them. Adopting a more experimental mindset is one of the ways to start getting some of the answers we need.

The European Commission has embraced the concept of ‘missions’ with Horizon Europe, and many innovation agencies are also planning to launch mission-oriented programmes in the near future if they haven’t already done so.

(Director, Innovation Growth Lab)

What does the task force programme entail and what does it aim to achieve?

Our ultimate aim is to create a change in both mindsets and practice of policymakers across Europe, institutionalised in processes, instruments and budgets: a change that encourages policymakers in this space to become more agile and innovative, continuously searching for new ideas to test rather than defaulting to the status quo, and that progressively transforms how member states use their own national budgets to improve their competitiveness.

This is why we’re pleased to be supporting Taftie’s new task force on experiments. We will help the network of European innovation agencies through a two-year-long programme of workshops on experimentation. The programme will be a blend of capacity building, peer exchanges of ideas and a platform for participants to launch experiments in their own home countries.

Why is it important to bring European agencies together through experimentation?

Becoming experimental it is a little bit of a journey. The barriers to policy experimentation are deeply ingrained in the day-to-day of innovation policymaking. Embedding a culture of experimentation across economic ministries and innovation agencies around the world will take time.

Experiments can make it easier for

risk-adverse organisations to venture into more innovative fields without having to commit large amounts of resources.

Getting to the end of the journey is much easier when not travelling alone. This is why Nesta set up the Innovation Growth Lab (IGL) as a global partnership of government agencies, in which we provide support to governments but also facilitate peer-learning between them so that they can learn from each other’s experiences. Since then we’ve been fortunate to count as partners some of the leading innovation agencies and ministries in the world, and as a result, today over 15 government agencies in ten Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries have launched or are actively considering policy experiments in this space. We hope the new taskforce will encourage more of them to go down this route.

How does being experimental help innovation agencies to be successful?

Policy experimentation encourages novel solutions to policy challenges and creates a dynamic of continuous improvement. Policy experiments can also help de-risk the process of exploring new policy ideas and changes. By starting small and testing effectiveness early, experiments can, in fact, make it easier for risk-averse organisations to sample novel approaches and venture into more innovative fields, without having to commit large amounts of resources (and thus reputation) in the process.

Experimentation also lowers overall policy costs, because, despite investing a little more upfront in learning and evaluation, experiments allow policymakers to ‘weed out’ ineffective programmes early on, potentially saving taxpayers from footing the bill. Ultimately, experimental policymaking leads to more learning, better decisions, more impactful policies and higher value-for-money.

How might this concept become increasingly important to future policymakers?

Over the next seven-year budget period European governments will invest over €1,000 billion in policies to support entrepreneurs and businesses to innovate and grow. If we want to maximise the returns on this substantial investment, we need more impactful policies and better evidence on their cost-effectiveness.

This is why at last November’s Eurogroup meeting of finance ministers we proposed setting up an experimental €1 billion productivity fund in the EU. This fund would identify, test and support the most promising interventions to accelerate productivity growth and increase competitiveness in Europe. Investing 0.1% (€1 billion) to find ways to maximise the impact of the remaining 99.9% represents a very modest investment, with huge upside potential. If this proposal is taken forward, it would have a transformative effect on innovation and business programmes in Europe, and the way policymakers develop new interventions.

At IGL, we believe that becoming experimental can help policymakers ask the right questions and get better answers.

www.nesta.org.uk/project/innovation-growth-lab/

To find out more about Nesta, visit www.nesta.org.uk/