Principles and practices of humanistic management

What does it mean to be an ethical businessperson? This is a contentious question, because there is no consensus about what code of ethics applies to commerce and economic life. Milton Friedman declared that the sole ethical – and practical – aim of a business was to maximise profits within the limits of the law. When speaking of publicly held corporations, business and economic thinkers sometimes render this as the theory of ‘shareholder value’ – the purpose of a business’s managers is to maximise its value to shareholders, which in practice means its profits, dividends and share value. Since the Global Financial Crisis, however, these views have been discredited by notable academics and business leaders alike (Mirowski, 2013). Notably, Dr Benito Teehankee, holder of the Jose E. Cuisia Professorial Chair in Business Ethics at De La Salle University’s Ramon V. del Rosario College of Business in Manila, strongly advocates shifting away from the theory of shareholder value. During the last 15 years, Dr Teehankee has conducted extensive research into the importance of businesses conducting their operations in a humanistic and socially responsible way. His research findings have driven his advocacy for fundamental change within the education curricula for management, national corporate policy and professional management practice.

The rise of corporate social responsibility

Recently, the notion of ‘corporate social responsibility’ has made progress in the business world, through which corporations deliberately pursue socially beneficial ends. The pandemic has hastened the shift toward a stakeholder model of corporate capitalism, following the US Business Roundtable’s move away from shareholder capitalism and embrace of the stakeholder concept in 2019. The World Economic Forum has released a set of stakeholder capitalism metrics in September 2020.

In the Philippines, there are considerable legal, moral and cultural traditions arguing for a more socially responsive commercial ethics. Dr Teehankee has furthered our understanding of the alternatives to the ‘shareholder value’ perspective. His critical realist action research and advocacy work outlines this shift in perspective towards humanistic ethics, in which corporations are encouraged to maximise their contributions to the ‘common good,’ and to nurture the human development of their workforces. Dr Teehankee works to embed ‘humanistic corporate governance’ and ‘humanistic management’ in business-school curricula, where ‘shareholder value’ doctrines traditionally hold sway. He has successfully lobbied for recognition of the broader interests of society in Philippine corporate regulation.

Teehankee’s work focuses on the non-material purposes of business, specifically its obligations to the wider society and its role in the human development

of its workforce.

Dr Teehankee advocates that businesses have a social responsibility to the communities they serve and neighbour. Firms must consider the environmental implications of their operations; they should foster high standards of employee welfare and design products and services that adhere to the spirit, and not just to the letter of the law. Dr Teehankee notes the importance of the boards of corporations setting strong humanistic and socially responsible policies and ethics. Specifically, this involves a holistic decision-making and policy-setting approach that considers the needs of all stakeholders (Fig. 1). Senior leaders must then role model the desired standards and behaviours, so they embed an ethical and socially responsible approach into the culture of the organisation. The significant corporate scandals of recent times, such as Enron and WorldCom, demonstrate how corporate governance practices are subject to mismanagement unless a socially responsible culture exists organisation-wide.

Dr Teehankee’s work favours the notions of stewardship and consideration of a business’s broader stakeholders. He devotes his corporate governance contribution to Essentials of investments (2018) to explaining how regulatory changes and corporate culture can encourage a genuine internal commitment to corporate social responsibility. More stringent regulation can encourage companies to operate in a more socially-responsible manner. However, the businesses that genuinely embody ethics are the ones that embed this ethos in their culture, so that employees at all levels are encouraged to report inappropriate behaviours and abide by the spirit of the regulation.

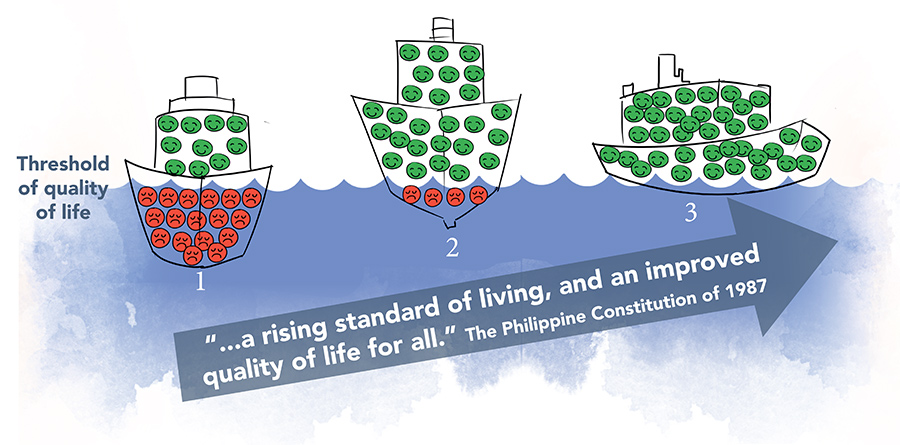

Dr Teehankee advocates for a stronger stakeholder orientation in Philippine corporate governance practice through several business columns and policy advocacy in collaboration with the Shareholders Association of the Philippines and the Management Association of the Philippines, leading professional associations for business leaders in the country. He authored a chapter specifically on ‘corporate social responsibility’ in Doing good in business matters: Frameworks (Santos 2008). Here, he demonstrates that the Philippine constitution and corporate legal code assume corporations serve a wider social function. Dr Teehankee discusses the moral and political shortcomings of Philippine corporate culture, where shareholding is highly concentrated in a few (often related) hands, and minority shareholders have little power or oversight – a situation that is deplorably opposite the Constitutional intention of “a rising standard of living, and an improved quality of life for all.” (Fig. 2 ).

Notably, as a result of Dr Teehankee’s work, there have been significant improvements in stakeholder standards in the Code of Corporate Governance issued by the Securities and Exchange Commission in 2016.

Managing humans

Dr Teehankee’s research explores the possible bases for an alternative system of business ethics and considers how this ethical framework might develop in practice. In one piece, ‘Humanistic Entrepreneurship’ (2008a), he outlines a new manner of managing business and the economy, drawing on Catholic social thought and other philosophical influences.

Dr Teehankee’s article focuses on the non-material purposes of business, specifically its obligations to the wider society and its role in the human development of its workforce. Catholic social thought strongly emphasises the importance of labour in the articulation and thriving of the human personality. ‘Humanistic Entrepreneurship’ describes three, progressively better, forms of labour management: ‘Instrumentalism,’ defined as ‘working through people’; ‘Collaboration,’ which is ‘working with people’; and ‘Humanism,’ the approach Dr Teehankee advocates, the practice of ‘working for people,’ specifically on nurturing the full development of their human potential (Teehankee 2008a: 98-99). Dr Teehankee argues that managers need to move away from viewing workers as another factor of production that needs to be monitored and optimised for productivity and efficiency. Instead, they should support their workers to meet their needs as human beings, including their physical and mental health, intellectual development, emotional growth, aesthetic experiences, social connectedness, moral and spiritual dimensions (Fig. 3).

Benito Teehankee’s work is a value-driven attempt to integrate ethical, humanistic thinking into current business practice and the formation of the business leaders of tomorrow.

In ‘Managing for Good Work,’ (2020), Dr Teehankee collaborates with the co-founder of a Philippine business to write about how this employee-focused style works in practice. Yolanda Sevilla and her husband lead The Leather Collection, which produces high-quality leather items as gifts. Sevilla treats the business as a ‘community of workers’ (magkabalikat sa hanap-buhay), (2020:127), thus encouraging her employees to invest themselves personally in their work. She encourages employees to seek out training and professional advancement (2020: 125-26). The case study discusses how Sevilla employs concepts like mercy, reform and responsibility into her company’s disciplinary practices, using individual case studies of supplier relationships and human resources interventions.

Ethics and humanistic management in education

In ‘Critical Research Action Research and Humanistic Management Education’ (2018a), Dr Teehankee criticises both the lack of strong ethics teaching in business schools and the dearth of practical research undertaken by their students. He urges business schools to promote ‘action research,’ which involves the close examination of real-life business problems through reflection on decision-making processes and the motivations that govern them, and the initiation of change interventions to enhance human development and business effectiveness. This research should be rooted in a ‘critical realist’ worldview, which accepts the existence of objective facts, but recognises that each subject has a partial, subjective view of those facts.

Dr Teehankee describes how De La Salle University’s business school constructed an action research course within its MBA program along these principles. The MBA is focused on developing ethical commitment to human development, change agency skills, and a critical realist understanding of management science. He provides an example of one MBA project that deals with chronic workplace discomfort. However, Dr Teehankee recognises that MBA programs might struggle to integrate action research into their curricula; accrediting bodies might question the need for the courses, and students may shy away from challenging but more substantial topics. Dr Teehankee suggests several measures to enable an easier integration, and he calls on business faculties to train academic staff in the action research process, so that they become comfortable with the method. To meet the requirements of the accrediting bodies, business schools should undertake “a rigorous follow-up study among its graduates” (2018: 88). Finally, MBA programs should encourage students to take a more critical stance towards orthodox business practices.

Conclusion

Building on his critical realist action research, Dr Teehankee strongly advocates humanistic management practices that place workers’ needs front and centre. Private business is among the most potent forces in our changing world. The leaders of enterprises large and small exercise immense power over the day-to-day lives of billions, the overall health of the global economy, and the environment. To shape the world we want to live in, we must influence the thinking and actions of these business leaders. Dr Benito Teehankee’s work is a determined, value-driven effort to integrate ethical, humanistic thinking into the development of the business leaders of today and tomorrow.

Personal Response

In your opinion, what are the biggest obstacles to implementing corporate social responsibility?

<> Extensive research has shown that the profit-maximising shareholder view is harmful to business and society. Unfortunately, this limited view remains dominant because it is the standard model taught in most business courses and, therefore, strongly shapes business practices. This model needs to be replaced with the stakeholder model in all business curricula. In combination with progressive business regulations, this will effectively integrate corporate social responsibility within the purpose and methods of business management.

In the field of business practice, a second obstacle is the use of financial statements as the main method of measuring business success. This practice seriously distorts business judgment because human welfare and environmental impacts are not reflected in these statements. More holistic reporting systems focused on sustainability and stakeholders need to be adopted.