Social context shapes age-crime distributions

Is adolescence a time when rule-breaking inevitably leads to a peak in age related crime and if so, what are the drivers and inhibitors of this behaviour? Ask a neurobiologist and they might point to a sea of adolescent hormones and still developing grey matter, as a driver of risk-taking behaviour. A psychoanalyst might speak about maturational forces of individuation and separation, and the need for adolescents to establish a unique identity. Some criminologists may say yes, the facts demonstrate irrefutably and repeatedly, a robust correlation between age and crime, with a spiking of crime occurring during adolescence.

Within contemporary Western societies such as the U.S. and the U.K., crime data has in fact over the past seven decades, shown an invariant age-crime relationship with peaks of arrests occurring during adolescence and a strong decline thereafter. A social scientist viewing this data, might ask is this pattern universally applicable or does the relationship vary in different societies across the globe, at different points in history and if so, what social structures influence adolescent engagement in crime and shape of the age-crime distribution?

Professors Darrell Steffensmeier, Yunmei Lu and Chongmin Na set out to explore whether societies and countries with vastly different socio-cultural influences, show different patterns in relation to age-crime data. This team of researchers gathered data from several countries with collectivist-hierarchical cultures and those with individualistic-egalitarian cultures and compared the age-crime distributions across these societies. The evidence they have gathered has enabled them to present a more cross-national non-Western perspective on age and crime, and to propose new understandings regarding the influence of social and cultural values and practices on crime within different societies.

The notion of highly self-oriented autonomy is a much stronger expectation in U.S. and Western societies than in East Asian societies, as we also can see in their differing approaches to Covid-19.

Age and Crime in Collectivist-Hierarchical Cultures

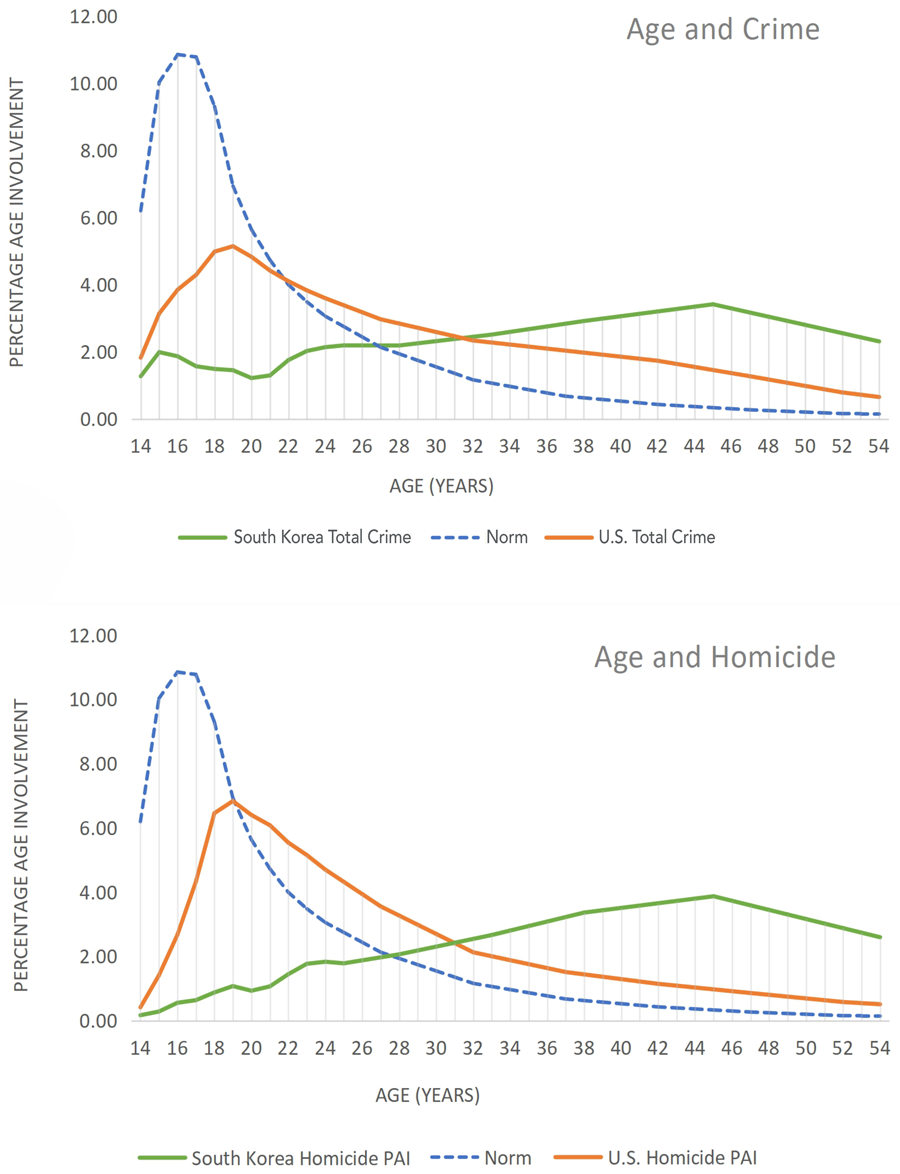

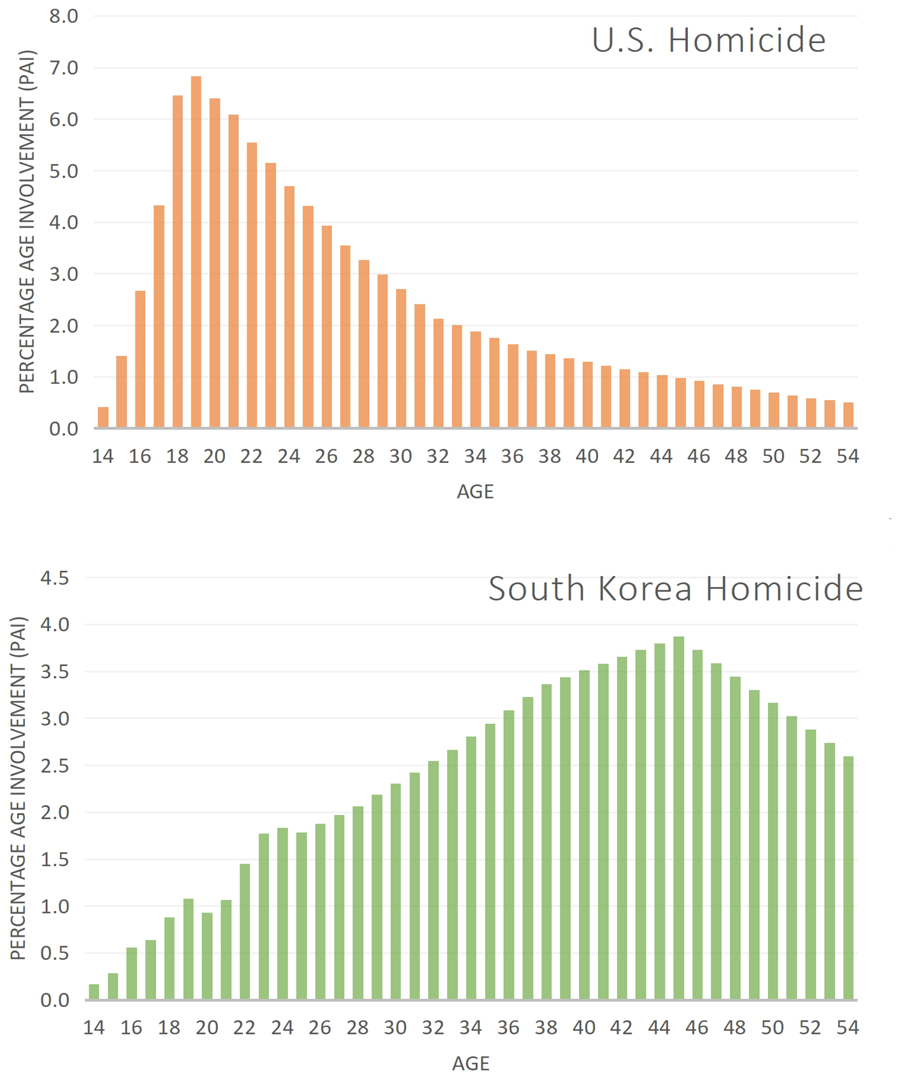

Professors Steffensmeier, Lu and Na state that South Korea has rich statistical information on age and crime types including drug violation, property crimes, and violent crimes. They have analysed data from South Korea and found that with the exception of an adolescent spike for ordinary theft (e.g. shoplifting), a clear upward age-crime trend is evident in the data, with crime peaking in the 30s (or older) and not during adolescence. A further analysis of the data suggests that this trend is not due to differences in crime reporting, law enforcement discretion or policing. Qualitative data gathered from criminologists and police officials has contextualised the ordinary theft spike in adolescence as “petty or minor misconduct” involving online games, gambling and shoplifting at malls (items such as clothing, cosmetics, cigarettes, alcoholic beverages, cell phones etc).

Turning to the data showing a post-adolescent upward trend with crime rising in the 20s and into the 30s or later, the research team say that evidence indicates a segment of the adult population in South Korea face cumulative economic and social hardship, and that this may influence criminal behaviour in this segment of the population. The researchers conclude by saying that South Korea with its collectivist-hierarchical cultural values, shows a clear age-crime pattern that differs from that documented in countries such as the U.S. and U.K., where crime peaks in adolescence. Of interest, is the fact that data from Taiwan – also a collectivist hierarchical culture – gathered and analysed by Professor Steffensmeier, Zhong and Lu (2017), shows a similarly lower concentration of crime offenses amongst the youth in this Chinese-Confucian country. This is the case also in India, a society with interdependent-hierarchical cultural values and practices, and crime patterns that are also “older and more spread out” than those in the U.S.

In South Korea and Taiwan, the developmental goals are clearer, namely the priority of preparing for the future by always trying hard and getting a good education that will help them succeed in adulthood for oneself and one’s family.

Shaping Adolescent Behaviour

Societies are also dynamic and change across time. Interviews conducted with researchers and public officials in South Korea and Taiwan suggested multiple ways in which the culture and practices of these societies, protect youth and promote conformity. By contrast, U.S. youth seem more exposed to opportunities and messages that promote deviance. Contrasting the data from these countries with different sociocultural structures, practices and beliefs, Professor Steffensmeier says there might be a way in which adolescence can be shaped to protect individuals from engaging in crime. Social practices that could be applied to reduce the risk for adolescents becoming involved in crime include encouraging adult-youth integration and reducing generational isolation through for example, joint family-youth social activities (e.g. visiting with kin on weekends) and adult-youth work exchanges, community functions and activities. Encouraging conformity with norms that emphasise the good of the group over the individual and providing clarity regarding adolescents’ developmental tasks (preparing for adulthood), is also likely to result in prosocial behaviour. Finally, monitoring and channelling behaviours and drivers (like aggression) that might shape adolescence is an additional important way of mitigating against the chances of a young person starting adult life on a wayward path.

Future Research Goals and Agenda

Professors Steffensmeier and Lu have set out a clear future research agenda with a focus on finding and collecting historical and cross-national crime data that will enable them to better document variations in age distributions of crime, and identify social and cultural practices and historical periods, that might account for this variation. Some of the challenges facing the researchers include accessing crime datasets that include detailed age-distributions in non-Western countries. Additionally, societies and nations are complex, often differing and overlapping in many ways – at times distinctive in their practices, while also increasingly blending and integrating diverse societal values, such that some show more of a combination of individualistic and collectivist values. For Professors Steffensmeier and Lu, the goal of their future research is to develop and offer a better understanding of nations such as the U.S. and U.K. which show adolescent spikes in crime, with a view to developing policies and approaches that protect young people from embarking on pathways with negative outcomes, when they enter adolescence.

Personal Response

What would your starting advice be to societies looking to reduce a high burden of crime?

<> According to Dr Steffensmeier, societies such as South Korea and Taiwan seem to provide considerably more in the way of protective monitoring, institutional engagement, as well as other forms of social “scaffolding” to support, protect, and shape the young adolescent in directions approved by the community or society during the window of vulnerability when the engines of adolescence turn on as a result of pubertal change. Our findings in these eastern countries suggest, that revitalisation of traditional institutions in the lives of teenagers and young adults may help attenuate the relatively high level of crime, particularly youth crime in some western countries.