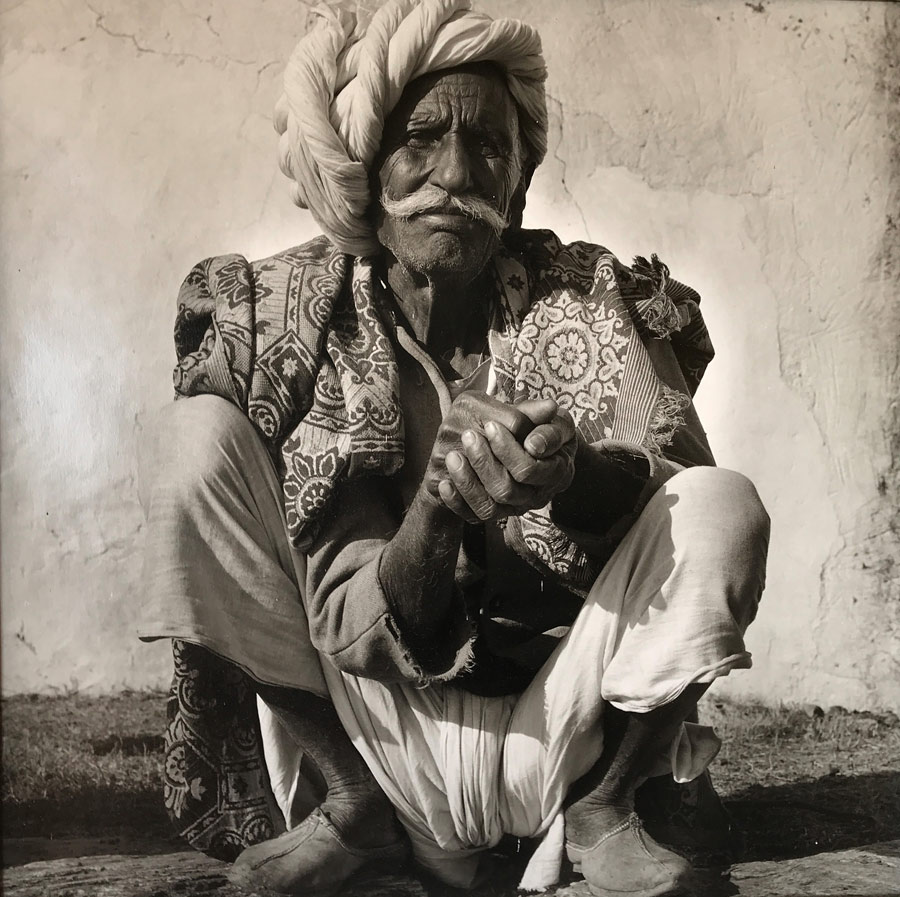

Thinking through livelihood: How a peasantry of princely Rājpuţāna became educated and activist rural citizens of Rajasthan, India

Professor Emeritus R. Thomas Rosin describes the complex system of rainfall harvesting, aquifer recharge, and lift irrigation used on lands bordering the Thar Desert in Rajasthan, India. He explores how this demanding system was key to the growth of formal education among the peasantry here during the pre-Independence period. As activism swept the countryside, a few would rise through formal education to positions in the royal administration to craft the very laws that would guide post-independence land reform in western India.

Rosin has spent many years over multiple visits to a complex 24-caste village community, stretching from 1964, just fifteen years after Indian Independence, until 2004. He conducted comparative research across the boundaries of the previous kingdoms known collectively as Rajputana discovering significant differences in livelihood. Their large joint families, uniting several generations into common households, their partnerships shared among families irrigating, and their egalitarian, supportive relations with in-laws in neighbouring villages, proved distinctive to the Marwar and Shekhawati regions. The solidarity and mutual trust enforced in their livelihoods lead to unity in political activism, shifting from social reform of their own traditions to open rebellion.

While referring to his own research and published accounts, he taps as well the historic lore of the Jat community, previously so central among activist tenants, as presented in their contemporary websites enriching the tale: JatLand.com, 2017.

OSTILL is Franck Camhi/Shutterstock.com

In this collection of writings on education in South Asia, Rosin’s chapter alone deals with informal education through on-the-job training and apprenticeships, as traditionally practiced in the countryside. He documents skills in monitoring, measuring, and computing among share-cropping farmers previously non-literate but numerative. Their inventive ways to actively thinking out problems stands in contrast to much of the rote memorisation then trained in village schools at the time of his studies.

How the system works

In this large and complex multi-caste village community in the Aravalli Hillls, Rosin observed livelihoods raising livestock and double crop farming, supporting as well many craftsmen and shepherds who raised but a single rainfed crop. Check dams collected rain run-off from the surrounding hills in numerous impoundments, such as reservoirs, ponds, and silt-ponds. By excavating and carting silts and manures to improve their irrigated fields, they kept the beds of reservoirs and ponds porous to soak and recharge groundwater. Across generations, they have reshaped the landscape to capture rain runoff to recharge the aquifers they tapped through shaft wells.

With educated descendants of peasants gaining positions of power, in a climate of rural and urban up-risings, the Maharaja and royal administration acted to reform the system.

Educated through apprenticeships working at these wells, four share-cropping families joined in partnerships. Sustaining trust in sharing equal inputs of labour and outputs of grain required careful monitoring of quantities and computing shares, encouraging a mathematics on a base 4. Pebble monitors tracked each lift of water from the wells, orchestrating shifts in the work force. Matching the acreage seeded with the anticipated reserves of groundwater to bring a crop to maturity depended upon remembering and learning from estimates made in prior seasons. Similarly, where to deepen a well or dig a new one was a probing about groundwater flows and pondering their relationship to surface collection of rain run-off. Rosin argues their skills in management to plan, irrigate, or expand their crop land. He gives an example of their mental arithmetic skills when recounting a visit to a goldsmith to buy gold through a tricky calculation of cost in one’s head. Such families though previously not literate proved numerative, collaborative, and empirically sensitive preparing their descendants for success in formal education.

Photo Credit: Gail Wread Rosin

Local farmers requested Rosin to study and put into writing their understandings about the hydrology of groundwater flows. Such publications and maps supported a village-wide petition to improve a levee and flow gate collecting rain water, which requires understanding how surface water influences groundwater supplies. Together, they changed the direction of a proposed government water scheme, and contributed to policies joining what had been the work of two separate government ministries.

Grand livestock fairs brought buyers from British India to purchase their bullock and camels, so prized as draft animals, while bringing together farmers and shepherds to both trade and socialise from distant villages. They shared aspirations and news, making them well aware of the nationalist movement under Gandhi and Congress Party in British India.

Land reform from Rajputana to Rajasthan

This village was in the Marwāŗ region of the Jodhpur Kingdom in the area of Rajputana (what would later become Rajasthan), which was ruled under a feudal system separate from, yet protected by, the British Raj, although the nearby town of Ajmer was under direct colonial rule.

While the Maharaja ruled, seventy percent of the land of his realm were held by various rulings classes of princes, lords, land-entitled priests, warriors, and moneylenders. Their share-cropping tenants paid ever increasing rents, free labour, and cesses to gain permission to perform their ceremonial religious, cultural and life-cycle rites and practices.

How Social Up-lift Became a Movement for Reform

Meanwhile in the kingdom’s capital Jai Narayan Vyas since 1920s joined others forming civil societies, each eventually banned, with leaders exiled or imprisoned. They set the urban scene for change. During the early 1940s Mool Chand Sihag’s Jat Farmer’s Reform Society of Marwar became among the first civil organisations not suppressed by the Jodhpur royal administration. Appearing at their anniversary conference gathering activist farmers, the Maharaja listens. The Maharaja goes further, perhaps influenced by the Jats within his administration and the non-violent resistence of these widespread, assemblies of peasants. His royal administration drafts the initial laws to sweep away the feudal land ownership titles and governance oppressing the countryside.

Up-risings and demonstrations in both the rural and urban sectors of his kingdom convinced him to aspire as a constitutional monarch to bring his realm into the 20th century.

What persuaded the Maharajas to make reforms exemplary for the future democratic province of Rajasthan

The ruler of Jodhpur mid-1940s was H.H. Maharaja Umaid Singh. The changes that came about during independence, Rosin contends, were possible thanks to the entrance of three Jats, well-educated descendants of share-croppers, into his administration.

The first was Mool Chand Sihag, a social reformer who laid much of the groundwork for the education of Jat tenants. He inspired the Jat youth with a thirst for education, and set up a chain of student hostels that allowed them to come to the towns to study in solidarity with fellow Jats.

The second, and one of those he so inspired and educated, was Kan Singh Parihar who trained as a lawyer and would later write the Marwar Land Reform laws.

Photo Credit: Gail Wread Rosin

The third was Buldev Ram Mirdha, who entered the Maharaja’s service as a postman, and eventually rose to become the police Deputy Inspector General. He was a strict law and order man, but had much sympathy for the suffering of the common people. He also helped educate Sihag’s students and bring them into the royal administration, and his power and influence helped dampen-down violence between the authorities and reforming elements during these turbulent times.

What did the activist achieve?

The non-violent, but coercive civil disobedience of satyāgrahā, empowered the peasantry to challenge the free labour, exorbitant rents, and cesses on their ceremonies. With educated descendants of peasants gaining positions of power, in a climate of rural and urban up-risings, the Maharaja and royal administration acted to reform the system of land ownership throughout his realm.

The inspiration and effectiveness of satyagraha in British India to force inquiry, fact finding, and negotiation led to the Maharaja replacing his British Lord as prime minister of his realm by the brilliant Indian Civil Service officer C. S. Venkatachar. Up-risings and demonstrations in both the rural and urban sectors of his kingdom convinced him to aspire as a constitutional monarch to bring his realm into the 20th century. Gandhi through his “experiments in truth” was empirically exploring how to enthuse and dignify his fellows as citizens, whether urban or rural, to create and sustain the institutions that would move ever closer to the rule of law, justice, and human rights.

Personal Response

In so uniting Anthropology with History through long-term research, what are your plans for future work?

<> By joining the archival works of Ramachandra Guha on Gandhian satyagraha campaigns in British India with studies focused on Marwar – such as Hira Singh on peasants petitioning their maharaja, Mayank Kumar on hydrology, Sobhag Mathur on civil resistance – I am detailing the links that brought Gandhian satyagraha strategies into the Rajputana princely states. As some maharajas of Rajputana replaced British lords as prime ministers of their realm with brilliant Indian Civil Service officers (such as C. S. Venkatachar), we can show in the most comprehensive way how an area was transformed without the massive tragedies that engulfed the rest of India at the time of Independence