Transitional care programs for older adults: Improving Canada’s core health services

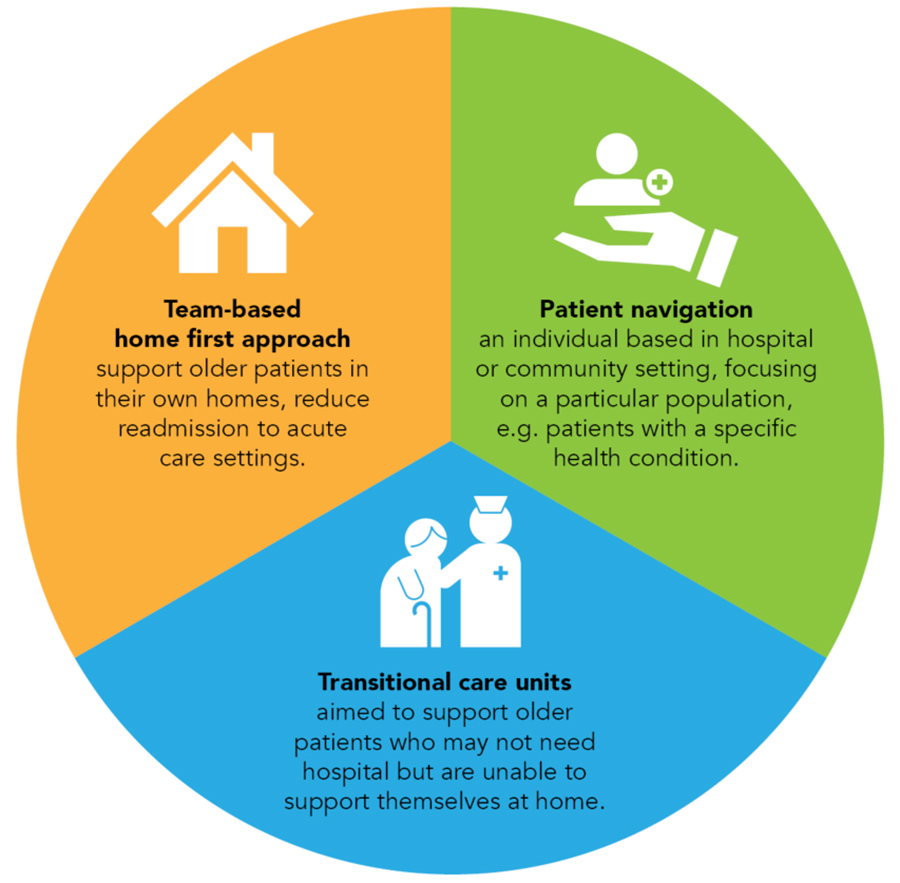

Transitional care aims to ensure the continuity and coordination of healthcare services for patients who are transitioning across different care settings, between healthcare providers and/or different levels of care within the same location. Examples of transitional care include assistance with medication management, care planning, family caregiver preparedness and home visits by health navigators.

Transitional care and older adult patients

Transitional care is important especially for older patients, as they are more likely to access different primary, secondary and tertiary healthcare services, including physician- and hospital-based services, home- and community-based services, and residential housing and care services. Transitions could be stressful for older patients as they are usually discharged with complex medical problems. Therefore, it is important for adequate planning and follow-ups to avoid poor outcomes. An ongoing challenge in Canada is how health services are often delivered in silos and contribute to negative patient experiences and worse health outcomes due to poor communication between healthcare providers, delays in delivery of care, poor coordination of care, and additional burden on unpaid caregivers. These challenges could prolong and worsen patient health outcomes and potentially place patients inappropriately in long-term care facilities.

Many older adult patients are not equipped to manage their own healthcare needs, nor do they have caregivers who could substantially assist in providing such informal care. Unpaid caregivers are commonly referred to as ‘secondary patients’ and require guidance and support to care for their loved ones. In the UK, for example, carers allowance is as low as £67.60 a week, the lowest benefit of its kind provided by the UK government. Reliance on unpaid carers varies across Europe, with the most accurate figures reported in the European Quality of Life Survey, which is undertaken every four years. The survey most recently found that Greece had the highest reliance on unpaid care, while the Czech Republic had incredibly low reliance, most likely as a result of its heavy dependence upon residential care. In Canada, it has been found that up to 96% of individuals receiving long-term home care have an unpaid caregiver, and a recent study by the Canadian Institute for Health Information has shown that more than a third of these unpaid caregivers are experiencing distress.

Benefits of transitional care programs

There is a growing amount of supporting data on the benefits of transitional care programs to address existing challenges across healthcare systems. Some of the identified benefits of transitional care include reduced unnecessary hospital admissions, re-admissions, and premature nursing home placements. Empowering older adults to manage their health at home and to age in place is important, while also freeing up resources in acute care hospital settings.

Older patients are increasingly experiencing complex healthcare conditions and require better chronic and continuing care to manage comorbidities and rising non-communicable diseases. There is an opportunity to improve healthcare services to meet these increased demands and ensure better use of resources and optimised health outcomes – or value-based healthcare – which centres on patients’ needs. Transitional care ensures increased integration and continuity of care to meet the medical and non-medical needs of older patients and their caregivers, as they move from different healthcare settings. This eases the pressure on acute care systems, as older patients could receive the appropriate care they need at the right place.

Transitional care ensures increased integration and continuity of care to meet the needs of older patients and their caregivers.

Gaps in transitional care

Although there is evidence to indicate the benefits of transitional care programs, there is limited information available to characterise the different models of care and availability of services across Canada. For instance, the lack of consistency in terminology used when referring to transitional care programs and healthcare providers make it challenging to understand and compare best practices across health sectors.

Moreover, there are limited opportunities for consistent uptake of transitional care programs across Canada without established guidelines for embedding transitional care programs as a core health service, as compared to the US, where a transitional care model is established, leading to its wide adoption to support older adults through their acute care transitions.

The context of transitional care internationally

The diverse definitions of transitional care, coupled with the commonly wide-ranging nature of the services provided, have meant that this form of care is not embedded or integrated within the Canadian healthcare system as a core health service. Professor Lori Weeks and Brittany Barber, from Dalhousie University, Canada, highlight the importance of looking beyond the Canadian context to assess how transitional care is managed and understood internationally.

A recent systematic review (conducted by Weeks et al, 2018) identified that transitional care programs across the US, Hong Kong, Canada, and other European countries were found to reduce rehospitalisation rates over time and increase the use of primary care services, which has a positive impact on preventative care. Preventative care is a cost-effective strategy to ensure patients are treated before their condition becomes chronic, which requires extensive resources to manage. This review also concluded that a one month or less transitional care program was as effective as long-term interventions in reducing hospital use.

A wide and varied range of initiatives exist globally to encourage transitional care, with varying levels of success and systems of implementation. In 2012, the Norwegian health system introduced the Coordination Reform, developed to ensure a coordinated and cohesive approach to healthcare. Norway introduced a binding system of agreements to streamline handover processes, such as admission and discharge processes, and cooperation between different areas and health authorities. In Singapore, a national Aged Care Transition (ACTION) program was launched to provide health coaching and self-management skills to vulnerable older adult patients. In the UK, where transitional care programs tend to vary regionally, several National Health Service (NHS) trusts are faced with the mounting difficulty of facilitating the smooth transition of older adult patients in acute care back into the community (often in the face of local NHS budget cuts and a deficit of space in acute care facilities).

A wide and varied range of initiatives exist globally to encourage transitional care, with varying levels of success and systems of implementation.

It is worth noting the importance of cultural preference and tradition in any discussion of these global divergences. Inevitably, caring for older relatives is a matter of great sensitivity, but nations tend to vary in the value they ascribe to different forms of care. Within Europe, we can think of the ‘staggered approach’ favoured by those in the UK, in which older adult relatives customarily enter a residential home when they reach advanced years, prior to transitioning to a care or nursing home. This is markedly different to the Mediterranean model, favoured in Italy, in which care is inextricably associated with the family home, and the intervention of the state in care provision might even be seen as a relinquishing of familial duty.

Improving transitional care as a core health service

Weeks and Barber conducted additional research to explore a small number of exemplar transitional care programs in Canada, as well as identify contextual factors that characterise challenges and learning opportunities from these programs. Nine interviews were conducted with stakeholders involved in the development of a transitional care program to uncover insights on their objectives, characteristics, and outcomes.

Weeks and Barber identified five important themes to focus on when developing transitional care programs in Canada:

1. Program scope

It is important to identify program goals based on the needs of a patient population, to optimise available resources and maximise patient outcomes.

2. Program structure

A collaborative effort between different healthcare professionals is needed, so services are not delivered in silos. The role of each healthcare professional should be defined clearly in the beginning, so everyone understands the role they play to support patients in their transition. Continuing education, training, and knowledge sharing are important aspects to strengthen the program structure, while ensuring everyone is aligned on the objectives of the program.

3. Continuity of care and individualised care

Every patient has a different set of healthcare needs. Therefore, a patient-centred approach is important when planning and transitioning to another service. By connecting patients with the appropriate resources, it ensures that patients receive the care they need.

4. Funding

Existing programs struggle with ongoing funding to hire additional healthcare professionals, as some patients require additional support and hours.

5. Health system infrastructure

There is an absence of a centralised electronic health record for information sharing, critical during the expansion of transitional care programs and communication between different healthcare professionals. Inconsistent regulations across different regions in Canada prevented the access to patients awaiting discharge from hospitals.

CONCLUSION

Additional research is needed to further understand the types of transitional care programs that exist in Canada. Results from this study indicate that transitional care programs that are operating across Canada, however, information is not widely disseminated by local health regions, especially in traditional academic peer-reviewed journals. Disseminating knowledge of the benefits of transitional care also supports investment towards embedding transitional care as a core health service.

Personal Response

Why do you feel there is a lack of consistency in the definition of transitional care programs?

In Canada, a lack of consistency in the definition of transitional care programs could potentially be explained by the lack of implementation of transitional care as a core health service. Given that Canada’s health system is delivered at the provincial level, and sometimes within regions of a province, there are often differences in terminology based on the way health services are designed, delivered, and funded. While the acute-care system is publicly funded and operated, publicly funded home care services can be delivered within the public system or by a private (not-for-profit or for-profit) agency. Also, differences may emerge depending on whether transitional care is seen as an extension of acute or home care. Because of the way health services are administered in Canada, there are many innovations or pilot programs that emerge within a province or region that are difficult to scale up and spread to other jurisdictions.