What can COVID-19 shutdowns teach us about reducing air pollution?

The impact of COVID-19 on manufacturing, travel and the associated pollutant production has proved an unexpected opportunity for a global experiment for atmospheric scientists. Drs Jenny Stavrakou and Maite Bauwens at the Royal Belgian Institute for Space Aeronomy are experts in atmospheric modelling and interpretation of satellite measurements of air pollution. They have been exploring how COVID-related changes have affected our environment and how we might use this to improve air quality in the future.

The atmosphere is a complicated place. Thousands of chemical reactions take place unceasingly, with a constant flux of new species coming in and out. Some of those reactions are triggered by different chemicals colliding with each other. Others happen when molecules absorb light from the sun.

The sheer number of different reactions and possible reaction routes makes modelling this chemical soup very challenging. Different layers of the atmosphere are home to different types of chemistry as not all wavelengths of light can pass through all the layers. Different regions tend to vary in their chemical composition as well.

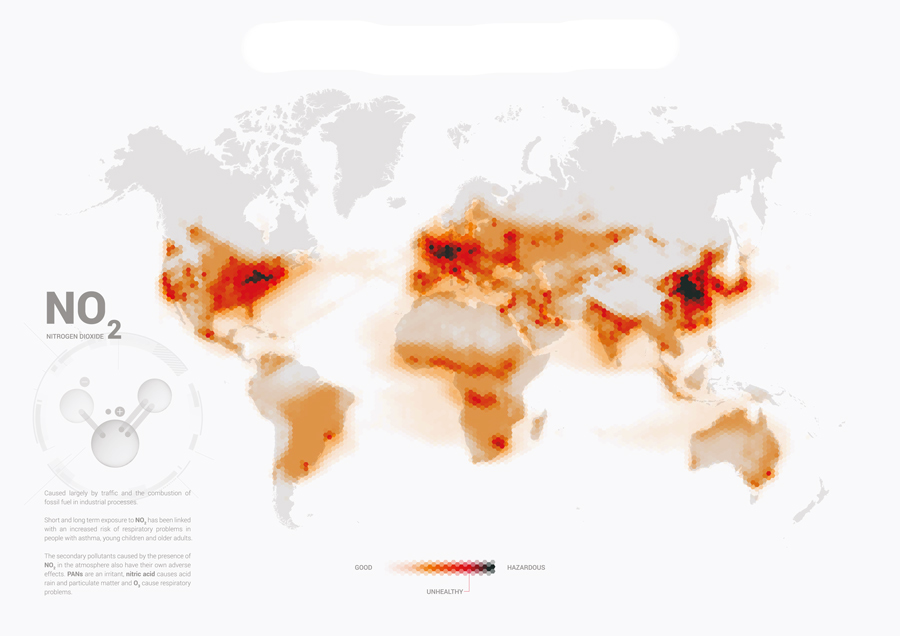

Despite its complexity, scientists internationally are working very hard to understand how our atmosphere is formed, as its rich chemistry has a direct impact on the quality of the air we breathe. Air pollution, harmful gases and particles in the air are serious global problems and are thought to be responsible for around 7 million deaths worldwide each year.

Of these air pollutants, nitrogen dioxide (NO2) is particularly detrimental in terms of impact on human health and the environment. High concentrations of NO2 itself can irritate the lungs and aggravate other respiratory diseases, like asthma. NO2 can also go on to react and form particulate matter and ozone – both of which have similar, problematic effects. In the environment, NO2 contributes to acid rain, damaging forests, coasts and even causing buildings in our cities to crumble.

NO2 itself can irritate the lungs and aggravate other respiratory diseases.

Dr Jenny Stavrakou and Dr Maite Bauwens at the Royal Belgian Institute for Space Aeronomy have been tracking NO2 levels using a special tool, the Tropospheric Monitoring Instrument (TROPOMI), aboard the Sentinel-5 Precursor satellite mission, dedicated to the daily monitoring of air pollution worldwide. They have been watching with great interest how NO2 emissions have been strongly reduced in response to the COVID-related restrictions of human activity, e.g. stay-at-home orders, travel bans and a fall in manufacturing. From the data they are recording, the team is working out exactly what the changing patterns of NO2 emissions mean for our environment and atmosphere, and what we can learn to help reduce air pollution in the future.

NO2 sources

Generally, NO2 and related molecules (known as NOx) are formed predominantly from the combustion of fossil fuels. Motor vehicles are a common source and even oil or gas burning at home, such as gas cookers, produce NO2. While very low concentrations are harmless, it can start to have negative effects when levels exceed 0.1 ppm.

Lemberg Vector studio/Shutterstock.com

The constant circulation and mixing of the atmosphere mean that even if the pollution is created in a localised area, it will eventually circulate globally. With TROPOMI, Drs Stavrakou and Bauwens have been focusing on the day-to-day change in NO2 levels in cities. While they have found some reduction in NO2 levels from new environmental legislation aimed at minimising air pollution, the most significant change has arisen from the COVID-19 pandemic.

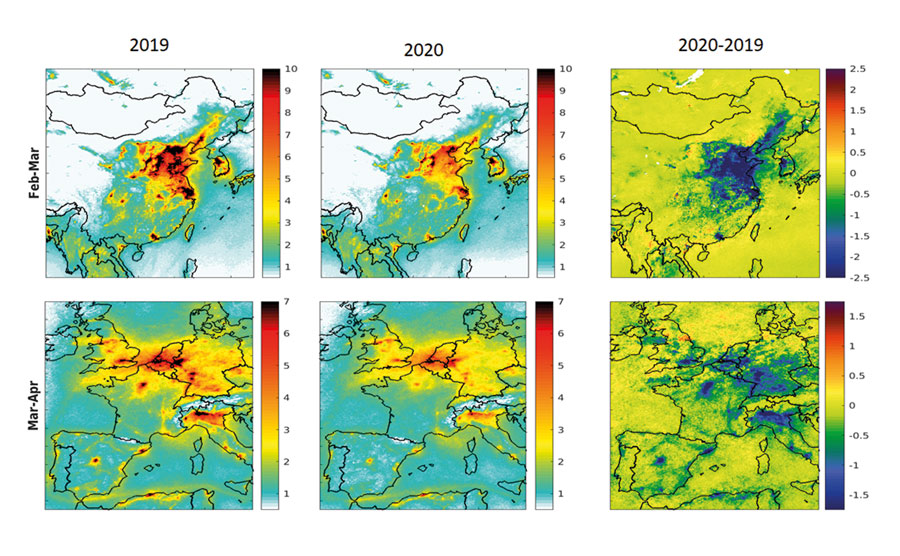

What the researchers learned was that, in many of the epicentres of the pandemic, the reduction in human activity caused a sharp and dramatic reduction in NO2 levels. Drs Stavrakou and Bauwens could therefore take a temporary glimpse of a world without nearly as much NO2.

Window of opportunity

Unfortunately for the environment, NO2 levels largely rebounded as economic activities have restarted, particularly in China and India. While global economic activities are still somewhat reduced post-pandemic, this has given Drs Stavrakou and Bauwens unique data to use to try and understand exactly what and how different factors contributed to the observed reduction in NO2 levels. While reduced economic activity played a role, meteorological factors also influence NO2 levels.

By having such extensive daily measurements on NO2 levels, the data from TROPOMI can be used to refine atmospheric models and a chance to see whether such models are still robust and reliable with a sudden reduction in the number of NO2 sources globally.

TROPOMI, which was launched on the Sentinel-5 satellite back in 2017, is not the only instrument to measure our atmosphere. Drs Stavrakou and Bauwens have also been comparing this with data from the Ozone Monitoring Instrument (OMI), another satellite launched in 2004, and found an excellent consistency between the two satellite datasets.

Problem gases

One of the reasons NO2 and the whole family of nitrogen oxides are so problematic for health and the environment are their effects on ozone. There is some concern that NO2 and ozone can work together to enhance their negative effects on the respiratory system. In the stratosphere, nitrogen oxides can destroy ozone, leading to a thinning of the global ozone layer which protects us from dangerous solar ultraviolet light.

Drs Stavrakou and Bauwens’s measurements make full use of the high-resolution capabilities of TROPOMI which allow them to identify exactly which regions and areas the NO2 emission originates from. Their measurements showed a reduction of up to 50% in NOx emission in some of China’s cities while COVID-19 lockdowns were in place. They have also been able to compare their satellite observations to local surface measurements. Models were able to simulate for the first time an unprecedented drop in emissions in many regions around the world and cast light on the response of the atmospheric system to the emission disruption caused by the pandemic. Generally, regions with reduced NOx production also showed decreased ozone production, but this was not the case everywhere. Surprisingly, in heavily polluted regions during winter, surface ozone has showed increases in response to the drop of NO2 pollution. This is because the relationship between NO2 and ozone concentrations and overall air quality is highly nonlinear. This shows that a reduction of NO2 emissions is often not enough to solve the pollution problem as a whole. The reduction of NOx concentrations during the pandemic also led to a cascading change in the concentrations of many other chemical species, showing how wide and large the knock-on effects from NOx could be.

Air quality control

As lockdowns occurred in the world during different time periods with different degrees of severity (which could be mapped in how much the NO2 emissions were reduced) a wealth of data was generated showing how smaller or bigger NO2 concentration reductions would impact the overall atmospheric chemical composition and how all of this could also be influenced by the weather conditions.As TROPOMI keeps on measuring NOx emission levels, COVID-19 lockdowns have provided a unique chance to examine how human activity has influenced the composition of our atmosphere, with many cities enjoying periods of significantly reduced pollution hazes and less respiratory irritation. Now, the question remains how to use this new knowledge to inform public policy going forward to address another public health crisis – air pollution.

Personal Response

Do you think the COVID-19 pandemic has raised awareness of air pollution and the importance of minimising NO2 emissions?

The air pollution changes due to the lockdowns attracted a great deal of media attention and mobilised in an unprecedented way the community of atmospheric scientists to work together and analyse the observed air pollution patterns. Besides its tragic dimension, the pandemic has shown that the air pollution problem is crucial and must be urgently tackled. As clean air swiftly returned in many polluted cities, from New York to Delhi and Beijing, the pandemic offered a glimpse of what can be achieved by speeding up the implementation of sustainable policies to make our cities healthier.