Deeper insights into cell death and survival

Cell death is not always detrimental. In fact, cell death is essential for normal development and for maintaining tissue homeostasis. All tissues must be able to tightly control cell numbers and protect themselves from rogue or unwanted cells that could disrupt homeostasis. In self renewing tissues, such as the skin or bone marrow, cell death is vital to make room for the many new cells every day. Cell death also plays a critical role in removing damaged, dysfunctional or potentially dangerous cells such as tumour cells and cells infected by viruses.

However, when this normal process goes awry it can have dire consequences. Impaired survival, excessive cell death and the loss of vital cells within healthy tissues is known to contribute to the development and progression of many conditions including many degenerative and autoimmune diseases. Conversely, too little cell death may promote the survival and accumulation of abnormal cells that can give rise to tumour formation and cancer. Understanding the intricate balance between cell death and cell survival in disease is hugely important. It not only gives an insight into the pathogenesis of a disease but may provide clues on how the disease can be treated.

Apoptosis is a form of programmed cell death that allows cells to ‘self-destruct’ when stimulated by the appropriate trigger. A carefully controlled process, highly specific and ordered sets of biochemical events play out, resulting in unique changes to the cellular morphology (structure) and ultimately cell death.

The discovery that Cyt c plays a role in both the life and death of a cell was profound.

Apoptosis is initiated by one of two separate pathways: the intrinsic pathway, which involves the mitochondria or the extrinsic pathway involving the activation of death receptors at the cell surface. The intrinsic pathway triggers apoptosis in response to a stress stimulus within the cell (such as damage to its DNA). By contrast, the extrinsic pathway begins when a signal is received from outside the cell instructing it to commit programmed cell death. In both apoptosis pathways, signalling results in the activation of a family of Cys (Cysteine) proteases, named caspases, responsible for the deliberate disassembly of the cell.

Cytochrome c: A death promoting factor

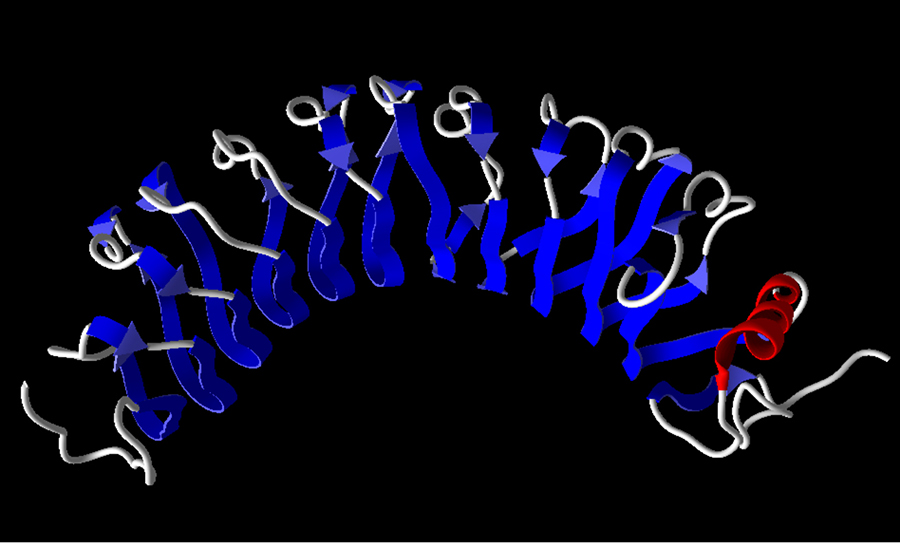

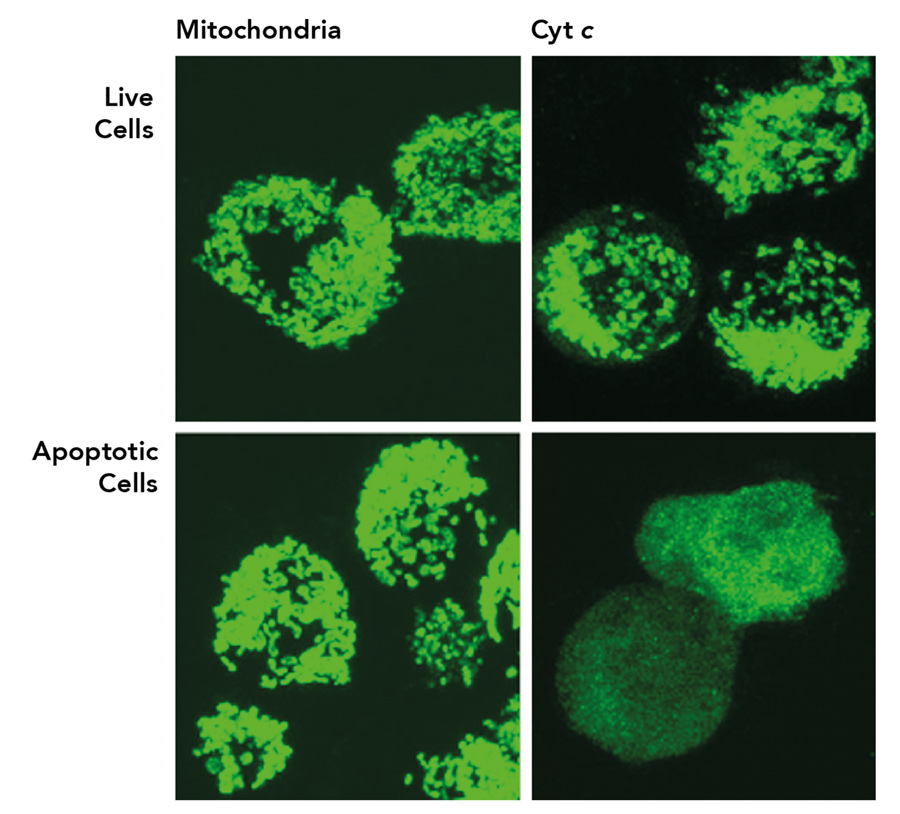

Cytochrome c (Cyt c) is a protein that resides in the mitochondrial intermembrane space. Here, it plays a key role in the respiratory chain, the process by which cells create energy. For many years, the biological function of Cyt c was assumed to be confined to its vital role within the mitochondria. This dogma was shaken in 1996, when a seminal study from Dr Xiaodong Wang’s laboratory, supported by Ronald Jemmerson and his team, demonstrated that Cyt c is involved in apoptosis. Removal of Cyt c from the cytosol, using a monoclonal antibody prepared by the Jemmerson laboratory, was found to eliminate the apoptotic activity, demonstrating that Cyt c, and not a contaminant, was responsible for the proapoptotic activity. A second monoclonal antibody from the Jemmerson laboratory, specific for a short section of the tail end of Cyt c provided the tool, in an assay in which cellular proteins lose their normal three-dimensional structure, to demonstrate that Cyt c moves to the cytoplasm during apoptosis.

These findings were quickly reproduced in other laboratories and to date the study has been cited in over 6,000 publications. It’s now known that following its release into the cytoplasm of the cell, Cyt c binds apoptotic protease activating factor-1 (APAF-1) where it promotes the formation of the apoptosome and subsequent caspase activation to bring about apoptosis.

The discovery that Cyt c plays a role in both the life and death of a cell was profound and has had a marked impact across the fields of biology and medicine. There is now much interest surrounding the potential of Cyt c as a clinical marker to detect aberrant apoptosis, with a view to exploit its role in cell death as potential therapy.

LRG1: A survival factor

Elevated levels of Cyt c in the blood are reported in patients with inflammatory conditions or in patients recovering from chemotherapy treatment for cancer. Thus, Jemmerson and his team set out to quantify levels of Cyt c in sera of patients using an antibody-based assay. However, these attempts were hindered by a component in serum that blocked the detection of Cyt c. The team identified this inhibitory component as leucine-rich alpha-2-glycoprotein-1 (LRG1).

Interestingly, they found that it bound to the same site on Cyt c as the apoptosis activating molecule, APAF-1.

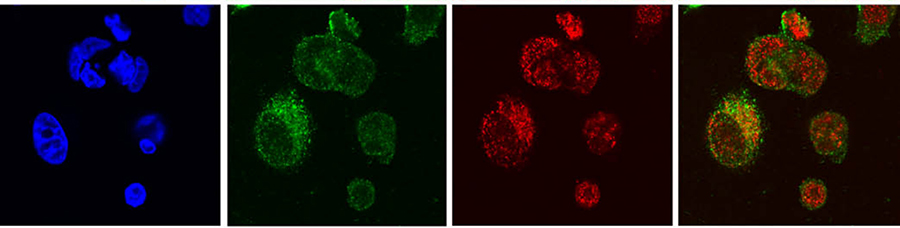

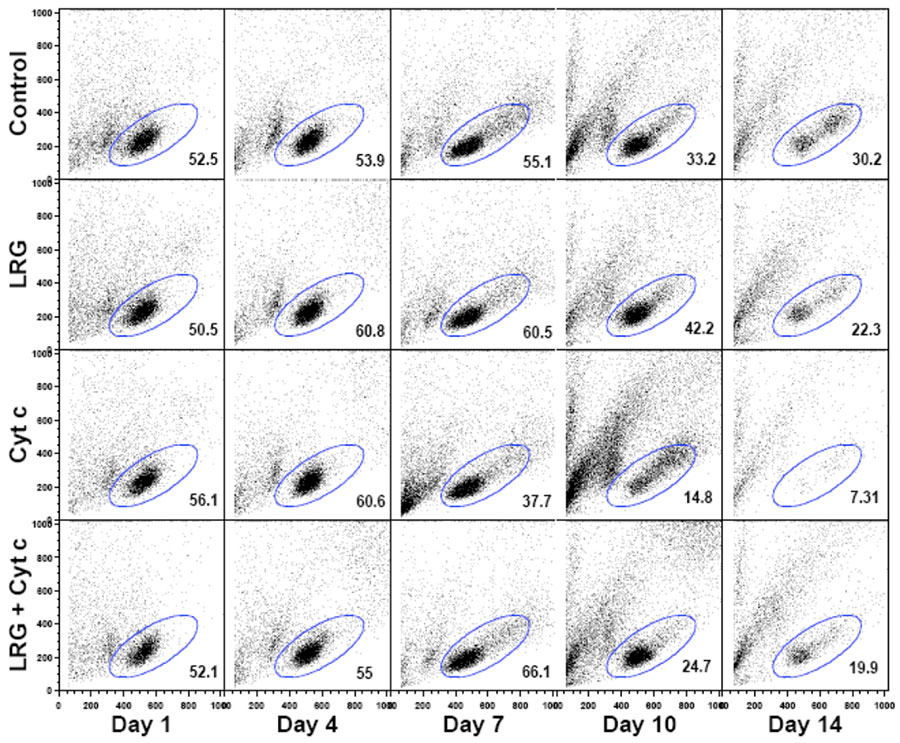

Keen to explore the role of LRG1 further, and especially its effect on binding to Cyt c, the Jemmerson laboratory carried out experiments using both human and mouse lymphocytes (a type of immune cell). Notably, they demonstrated that LRG1 acts as a survival protein, protecting the cells from apoptosis induced by extracellular Cyt c. The researchers hypothesised that LRG1 may protect cells from apoptosis by sequestering Cyt c. In fact, the team discovered that the mechanism of protection by LRG1 appears to involve active signalling. That is, when LRG1 binds to Cyt c it seems to interact with a receptor on the cell to deliver a survival signal. They showed that mouse LRG1 was more effective than human LRG1 in protecting mouse lymphocytes against extracellular Cyt c induced apoptosis, suggesting that a species-specific component plays a role in transmitting the survival signal to the cell. To date this component, perhaps a cellular receptor, remains to be identified.

In a recent publication in the journal Apoptosis, Jemmerson and colleagues reported that LRG1 is present in the cytoplasm of a breast cancer cell line, where it protects against apoptosis by binding cytoplasmic Cyt c and preventing its interaction with APAF-1 that would otherwise initiate cell death. In this study, MCF-7 breast cancer cells that had either increased or decreased expression of LRG1 were exposed to the apoptosis inducing agent hydrogen peroxide and the effect on cell survival was examined.

The action of LRG1

In a series of elegant genetic studies, LRG1 expression was increased in cells. The research team showed that these cells were more resistant to hydrogen peroxide induced apoptosis than control cells. Conversely, cells with decreased LRG1 levels were more sensitive to hydrogen peroxide induced apoptosis. Interestingly, although more Cyt c was detected in the cytosol of cells with higher LRG1 levels than in the cytosol of either control or cells with lower levels of LRG1, the Cyt c was bound to LRG1, not to APAF-1, and therefore unable to induce apoptosis. Thus, in contrast to the mechanism of protection offered by extracellular LRG1 previously reported for lymphocytes, the mechanism of protection in this case appears to be due to steric hindrance whereby part of the LRG1 structure physically blocks Cyt c from binding APAF-1. As LRG1 binds Cyt c with a much higher affinity than does APAF-1, it may serve as an effective trap to capture Cyt c that would appear in the cytoplasm. It’s thought that LRG1 may normally protect against transient increases in Cyt c released to the cytoplasm in the absence of committed apoptotic signalling.

LRG1 acts as a survival protein, protecting the cells from apoptosis induced by Cyt c.

Once committed apoptotic signalling occurs, in this case, following exposure of the cells to hydrogen peroxide, LRG1 was found to be degraded, allowing Cyt c to bind APAF-1 and activate the intrinsic apoptotic pathway. Thus, in the absence of committed apoptotic signalling, cell survival is affected by the ability of cytoplasmic LRG1 to block Cyt c binding to APAF-1. As a consequence, dysregulation or increased expression of LRG1 in cells may support the development of cancer and exacerbate inflammation and autoimmunity.

In addition to its important role in apoptosis, it’s known that Cyt c can serve as a damage-associated molecular pattern (DAMP), molecules released by damaged or dying cells capable of alarming the immune system to any danger. Thus, Cyt c appears to perform distinct functions depending upon its location. Under normal conditions, Cyt c resides in the mitochondria playing a vital role in the respiratory chain. In response to pro-apoptotic signalling, its translocation to the cytoplasm initiates the process of cell death. Finally, upon loss of membrane integrity and its release into the extracellular environment it may have a proinflammatory role aimed at inducing and facilitating the repair of host tissue.

The work of Ronald Jemmerson and his team elegantly shows that the binding of Cyt c to LRG1 promotes cell survival. Thus, when Cyt c is displaced from its usual location in mitochondria, either within or outside the cell, and in concert with its binding partners, APAF-1 or LRG1, it plays a pivotal role in the balance between cell death and survival.

Personal Response

Is it possible to exploit/manipulate the binding of LRG-1 to Cyt c to modulate the life or death of a cell as a potential therapy for those diseases associated with defects in apoptosis?

<>

By testing 1,200 commercially available off-patent compounds for blocking LRG1 capture by Cyt c in an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay we found several candidates that blocked LRG1 capture but did not bind Cyt c and, thus, should not interfere with APAF-1 activation. The exceptionally high affinity of LRG1 for Cyt c reported by others will present a challenge finding a competing compound effective systemically at concentrations allowable by prescription. An antibody approach is also possible for impacting extracellular LRG functions as shown by John Greenwood’s research group in inhibiting pathogenic neovascularisation induced by LRG1.