How do power imbalances influence national corruption and welfare?

Professor Wolfgang Scholl of Humboldt University in Berlin, Germany, has built a

detailed model that shows how and where corruption thrives and the damage it causes to social welfare. The social-psychological, cultural, and economic causes and effects are disentangled, and the ethical imperatives are discussed that support a positive outcome. The model confirms empirically that unequal power relations induce corruption and foil welfare. More equal power relations, signifying a deep-rooted democracy, are a good basis for a healthy society.

Baron Acton’s insight that ‘power tends to corrupt, and absolute power corrupts absolutely’ neatly expresses the social-psychological evidence that exceeding power corrupts actors morally and materially, and that such immoral behaviour escalates as their dominance increases. Investigating whether this also holds true within nations, Professor Wolfgang Scholl of Humboldt University in Berlin, Germany, together with Professor Carsten Schermuly, examined how a steep power distribution fuels national corruption and thereby affects a country’s economy and the welfare of its inhabitants.

Expressions of power

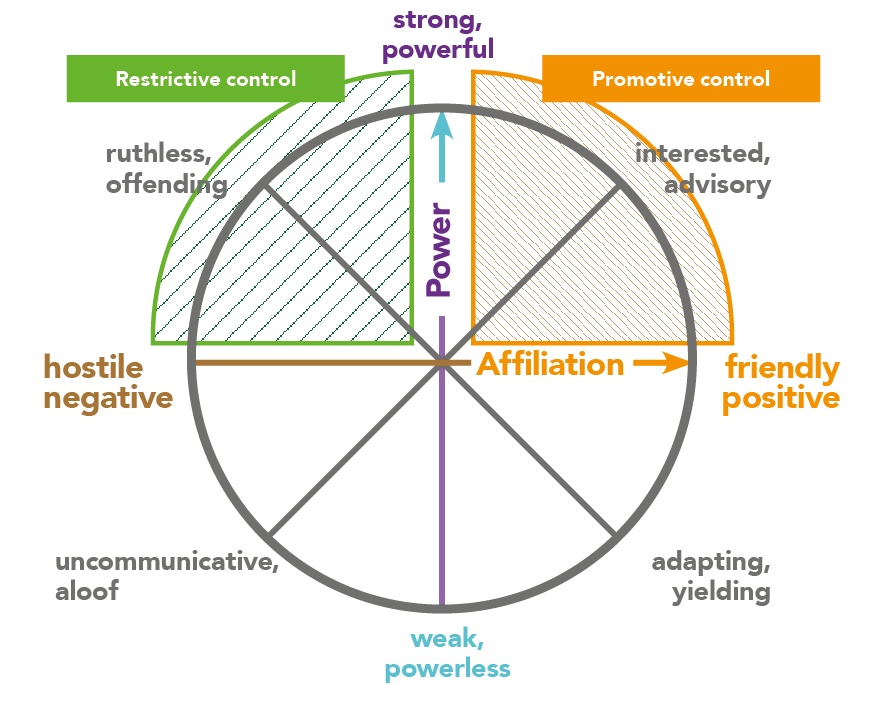

Social power is the capacity to change the thoughts and behaviours of other people. The more power people or social systems have, the more they are able to exercise control for actual purposes, especially if the other side is less powerful and does not try to counter such actions. Power is a capacity which may be used in different ways. Scholl has developed a model of power relations that identifies two principal ways of using power, called promotive control and restrictive control. When strongly pursued, a power relationship is either used inclusively, respecting the autonomy and the interests of the other side (promotive control), or it is used in an excluding way, violating or ignoring the autonomy and the interests of others (restrictive control). Early in life, children experience both kinds of control from their more powerful parents, hopefully mainly the promotive one.

The importance of this distinction becomes irrefutable if power is realised as the second basic social dimension beneath affiliation (see figure 1). These two dimensions are sometimes also called ‘agency’ instead of power and ‘communion’ instead of affiliation. Social psychology sees these two as most basic and relevant for all kinds of social actions. It follows that any use of power is automatically judged by those concerned to be either friendly and positive, or hostile and negative, depending on the respect or violation of one’s interests and autonomy.

Material corruption is one of the instances of restrictive control – using power for personal gain against the interests of others, often against the whole community. This equates to Transparency International’s definition of corruption as ‘the abuse of entrusted power for private gain’. But power can also be used as promotive control, using the levers of social and institutional power to promote the economic and social welfare of a country’s citizens. Power may tend to corrupt, but it can also be used to promote the wider societal benefit – that’s what people expect. The latter is more likely if there are checks and balances vis-à-vis power positions because, in this way, corruption is discouraged through specific fines. When power is balanced and people are free to tackle emergent problems in all conscience, cooperation becomes more effective and learning and innovation flourish. But in a steep social hierarchy, more restrictive control is likely because the dominant persons and groups don’t fear detection and punishment, and the silenced majority accepts that situation and resigns. This not only has bad consequences for the suppressed persons and groups: history is full of autocratic and dictatorial regimes where leaders and higher echelons could not be criticised and the lack of controversy led to misjudgments and devastating results for the whole country.

In order to investigate these theoretical predictions derived from extant research, the different power distributions within countries have to be empirically measured and compared on a common scale.

Scales of power distribution

Measuring the power distribution in a country can be done with political indicators (e.g. degree of democratisation), economic ones (e.g. the wealth gap), and cultural-psychological ones (e.g. suppression experiences). The authors prefer such cultural-psychological measures like Hofstede’s Power Distance index because such items reflect best the everyday experience of hierarchical power.

For Power Distance, respondents estimate for example on a 5-point scale, “How frequently, in your experience, does the following problem occur: Employees being afraid to express disagreement with their managers?” Taking this study as a starting point, the researchers added three other global scales: GLOBE’s In-Group Collectivism from House et al. (e.g. “In this society, people encourage group loyalty, even if individual goals suffer”) correlated highly with Power Distance, because upper management often demands loyalty and undermines autonomy. Hofstede’s Individualism correlated inversely with both (e.g. “Considerable freedom on the job”), and so did Van De Vliert’s Freedom Index, which includes freedom from political autocracy, press repression, and discrimination. By reversing the Power Distance and In-Group Collectivism scales in line with Individualism and the Freedom Index, the combined measure of these four indices provides a more reliable and valid measure. It identifies the extent to which a country exhibits a culture of freedom underpinned by balanced, more equal power relations, called Power Balanced Freedom (PBF). The PBF measure is available for 85 nations.

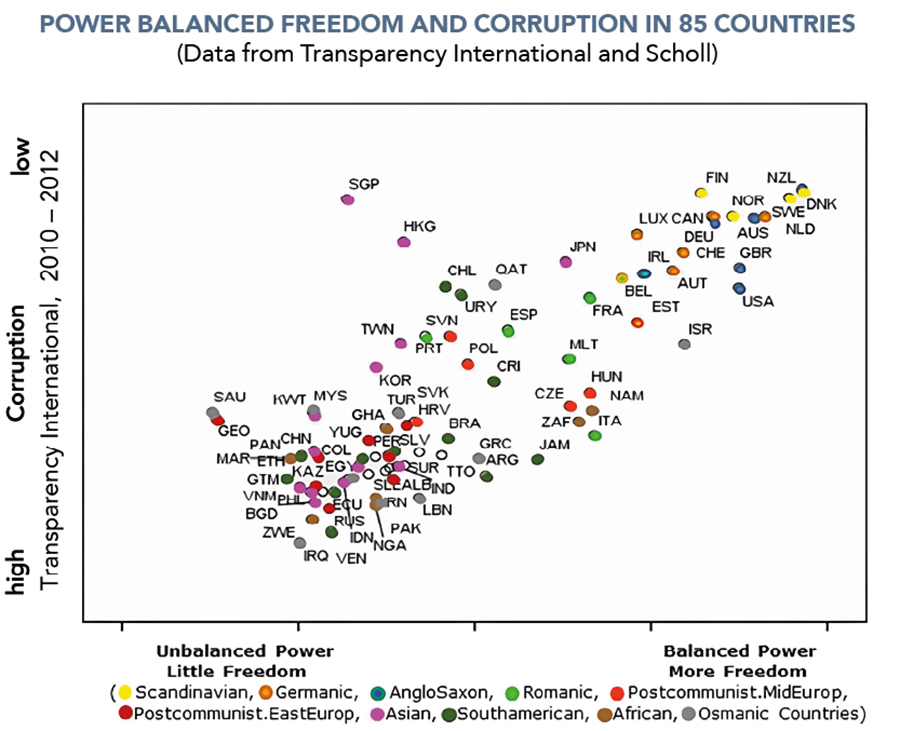

Power may tend to corrupt, but it can also be used to promote the wider societal benefit.Corruption data from Transparency International are also available for these nations, so that both data sets can be correlated. The remarkable result can be seen in figure 2 by plotting each country on both scales. Countries with cultures fostering balanced power relationships and supporting individual freedoms are associated with lower levels of corruption. Countries with highly unequal power distributions are strongly associated with corrupt practices.

Scholl postulated that more Power Balanced Freedom (PBF), i.e. less restrictive control, leads to less Corruption. The results in figure 2 seem to confirm this expectation, but the causal assumption, that higher PBF is the source of lower Corruption cannot be concluded from such a correlation. A test of causal assumptions can only be done with a more complex theoretical model and a fitted statistical model called path analysis.

Countries with related cultures are marked with the same colour.

Extending the theoretical model and testing its causal paths

If a higher PBF leads to less Corruption, this should lead to an improved economy, measured in terms of Gross Domestic Product (GDP), the classic measure of economic achievement, because public resources are not wasted for private gain and are invested into common goods. GDP in turn should lead to greater welfare, because more money is available for health/life expectancy, education, and income, dimensions contained in UN’s Inequality adjusted Human Development Index (IHDI). This index measures not only the mean life expectancy, education, and income per country, it is adjusted for incorporating the spreading of these goods.

Corruption might also have a direct negative effect on IHDI, because even if public resources are invested, corrupt decision-makers might invest more in their prestige objects like big palaces instead of needed infrastructure. Additional variables discussed in the literature, which might complement the mentioned effects, were also tested. Tests are done with path analysis; statistical details can be found in the original article.

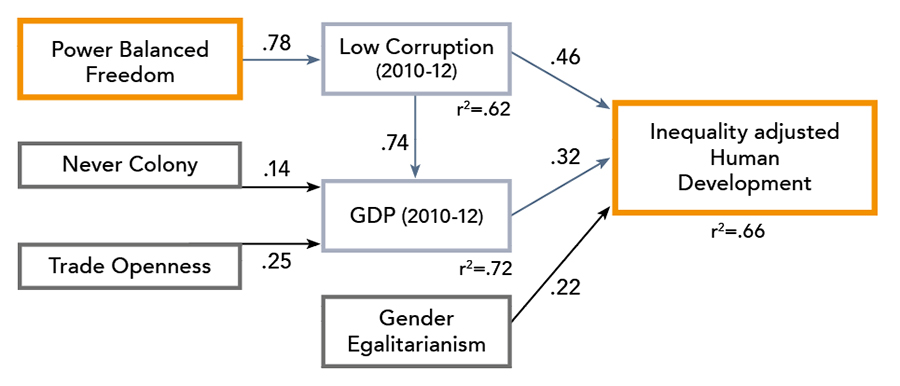

The proven effects can be seen in figure 3 where cause-to-effect paths are indicated by an arrow. Power Balanced Freedom, representing the countries’ power distribution, is the best predictor of low Corruption. Economic achievement (GDP) could be impressively predicted by Corruption; Trade Openness, furthering economic competition, and Never Colony, being not hampered by a distorted culture, added further parts of the GDP explanation. National welfare (IHDI) is dependent on low Corruption, GDP, and Gender Egalitarianism, the extent to which women’s discrimination is minimised. The empirical data confirm these causal assumptions perfectly.

Power Balanced Freedom, representing the countries’ power distribution, is the best predictor of low corruption.PBF’s direct causal effect on (low) Corruption is very strong (.78) and explains nearly two-thirds of Corruption (r2 = .62). No other cultural, political, and economic variables could complement the PBF→Corruption effect. Low Corruption has positive effects on economic achievement (Corruption→GDP: .74). The two additional determinants of GDP are less important than Corruption, Trade Openness with .25 and Never Colony with .14, but they help to improve the GDP explanation by Corruption from r2 = .54 to .72. No other tested variable (e.g. Human Capital) could further improve the GDP explanation. Interestingly, some authors postulate a reverse effect of GDP on Corruption, assuming that people in poorer countries have a stronger incentive to do corrupt deeds. The two contrasting assumptions, Corruption→GDP and GDP→Corruption, had previously never been tested simultaneously. This was done for the first time in this study; the reverse effect of GDP on Corruption was not significant, almost zero, and was omitted in figure 3. Finally, low Corruption had a strong effect on citizens’ welfare, directly (Corruption→IHDI: .46) and via GDP (Corruption→GDP→IHDI: .74 x .32 = .24).

Over the last decade, the UN IHDI data indicates that national welfare is highest in the Scandinavian countries followed by German- and English-speaking countries. These are exactly the countries with highest Power Balanced Freedom (PBF) and least corruption (see fig. 2). The empirically confirmed model (fig. 3) shows that welfare is attained through very low Corruption (.46) and high GDP (.32), which is itself dependent on low Corruption (.74). Gender Egalitarianism (GE) is another distinct aspect of a more equal society which is directly relevant for national welfare, apparently through a different political opinion formation. These three determinants together explain very well the Inequality adjusted Human Development Index for national welfare (r2 = .66).

The importance of culture

Several scientists, especially from economics, assert that culture has no decisive influence on corruption. Instead, they assume deficient societal institutions as the main cause. But their investigations use inappropriate measures of culture, like proportions of religious denominations or percentages of women in public offices, which are too crude to represent cultures. The path model proves the opposite: Culture is the most important determinant of Corruption; institutional measures are somewhat less predictive and cannot add further explanations. Culture shapes institutional structures and helps to construe their processes.

The primacy of culture over formal institutions is easy to see by looking at European countries in figure 2, which are clustered according to their languages and histories. The shared cultural values of the Scandinavian countries put them at the highest PBF and lowest corruption level, whereas several other EU countries are clearly way down the scales, the Germanic and Anglo-Saxon countries next, then the Romanic ones, the post-communist Middle-European and Eastern-European countries last. Moreover, three of the four exogenous variables in the model are cultural variables: PBF, GE, and Never Colony, the latter reflecting the devastating effect of colonisation. The importance of culture can be quantified: PBF delivers a total effect of .54 on national welfare (IHDI). Cultural equality, spanning PBF and GE, has a joint effect on IHDI of .70, and together with Never Colony, the culture effect amounts to .73. This is much higher than the economic Trade Openness effect on IHDI via GDP: .25 x .32 = .08.

A deep-rooted culture of equality provides high living standards for most citizens.Low Corruption alone has also a very strong total effect on welfare (.70), with a direct path and an indirect one via GDP. Why has a corrupt culture such a strong effect? It seems that Corruption is the tip of an iceberg where several other malfunctions are below the waterline. The iceberg itself might be the lack of trust and reliability leading to fragile daily cooperations because opportunities for own gains are given priority over community outcomes, induced by exceeding power and restricted freedom (i.e. low PBF).

Ethics behind moral landscapes

Culture guides human thoughts, feelings, and actions with specific norms embedded in moral landscapes, i.e. what should be done and what should be avoided. Ethics can philosophically reconstruct the logic behind moral landscapes and may therefore deepen the understanding of Power Balanced Freedom and its consequences. The more power is unequally distributed and the more often it is abused, the more freedom and autonomy of many people are unnecessarily restricted. The ethical basis of moral action is the freedom to decide between more or less moral acts.

To deny others this freedom by using restrictive control while requiring freedom for oneself is not justifiable. Power has to be used promotively, respecting the autonomy of concerned others. Thus, restrictive control is ethically only justifiable as needed sanction by a community against someone’s restrictive control (e.g. reputation loss, fines, jail) in order to minimise restrictive control within the community. This deontological approach, where moral actions follow a universal promotive control code, is the core of PBF. PBF in turn supports practically – notwithstanding philosophical distinctions and disputes – a utilitarian approach which seeks the highest welfare of all citizens like UN’s IHDI.

Conclusion

The confirmed importance of Power Balanced Freedom (PBF) and Gender Egalitarianism (GE) underlines the advantages of democracies with well-functioning checks and balances and a responsive use of guaranteed freedoms. A deep-rooted culture of equality provides high living standards for most citizens.

Countries with low PBF, i.e. autocratic and dictatorial regimes, are plagued with high corruption and suffer from low Inequality adjusted Human Development, i.e. low and broadly spread life expectancy, education, and income. Even worse, the stabilising character of culture implies that those countries have a hard time progressing in their wanted human development: cultures change very slowly. Nevertheless, the advancement of Power-Balanced Freedom gives a procedural framework for pursuing higher welfare across the world.

Personal Response

What inspired you to conduct this research?My research on groups and organisations has shown that power used as promotive or restrictive control has dramatically different consequences. So, I was curious whether similar differences appear on the state level with corruption as a central example of restrictive control. My personal political interest in the future of democracy strengthened these considerations.