How virtual reality is helping to rebuild a community devastated by the Fukushima disaster

Tohoku in the north of Japan’s largest island, Honshu, was for centuries a remote region known chiefly for the beauty of its mountains, lakes and hot springs, as well as its harsh climate. All that changed on 11 March 2011 when a gigantic earthquake measuring 9.0 on the Richter scale hit the region. It triggered tsunami waves up to 14 metres high and led to the meltdown of the Fukushima nuclear power plant.

More than 18,500 people were killed in the disaster now known as the “Great East Japan Earthquake”. An additional 154,000 people were left without homes or were forced to flee nuclear contamination in the 20-kilometre evacuation zone established by the government. Around 26,000 people in the three districts hardest hit by the tragedy have lived in temporary accommodation for years. Thousands of others have dispersed to other parts of the country, often hundreds of miles from the place they used to call home.

As in many countries, the nature of Japanese society has changed much in recent years. Even before the disaster, Japan was facing the challenge of how to cope with both an ageing society and an altered familial structure in which fewer elderly people live (as traditionally) with their eldest son in a multi-generational household.

As a result, although some Fukushima evacuees have gone to live with family members, many others, especially elderly people, now live alone. The isolation they feel – not only through being separated from those closest to them, but also through their displacement from the home and community that for generations formed the backdrop to their family’s lives – is of increasing concern.

Accessing Namie via a phone line has a similar function to visiting a Shinto shrine.

Also worrying is that, upon relocation, younger generations hesitate to talk about where they came from, for example when starting a new school. Being an evacueee can be stressful and may make people feel stigmatised, and even lead to bullying, because others wrongly think that radiation can be caught, like a virus. They may also suffer jealousy from neighbours, for example, if they use their compensation money to build a new house, or because they are entitled to other benefits such as free hospital fees and highway tolls. As a result, many people keep themselves to themselves and feel like they are living in hiding.

in the disaster now known as the ‘Great East Japan Earthquake’.

Narrative power

Dr Kanako Sasaki from Tohoku University has been studying the effects of the Great East Japan Earthquake on the inhabitants of one town in Fukushima province, Namie, the birthplace of her father. In 2010 Namie’s population was around 22,000. Farming and fishing were the main sources of employment, but it was not a wealthy area and many family members worked as migrant labourers in other parts of Japan.

The Tokyo Electric Power Company’s (TEPCO) decision to build a nuclear plant nearby brought much-needed employment. But one day after the disaster, when residents were forced to evacuate, Namie’s population fell to zero. Although some people began to return when restrictions were lifted for some areas in 2017, many are reluctant to do so and fewer than 10% have so far returned.

With a background in the arts and sociology, Dr Sasaki’s interest lies in the power of narrative – the told and untold stories of the disaster’s survivors. For her project “Archive Namie: protecting memories”, she began by interviewing Fukushima evacuees still living in temporary accommodation. Dr Sasaki explains: “Listening to the compelling stories told by these interviewees, we discovered that elderly person survivors in particular had no choice but to accept their isolation and solitary life and the temporary housing that has become their home of last resort.”

The consequence is that many Fukushima survivors feel they can’t talk about the disaster or where they have come from. It’s as if the past has disappeared. In the wider context there is the added historical cost of people’s memories and culture being lost to future generations.

Dr Sasaki aims to change this and help people tell their stories, anonymously if they wish. She hopes that this will help people who didn’t experience the disaster to understand evacuees and empathise with their situation. In addition, she hopes that turning evacuees’ experiences into art will help them to release some of the feelings they have kept hidden. “This is the power of narrative – of live stories,” she said.

The project

Dr Sasaki’s project to archive people’s memories of Namie is based online. This allows evacuees to access it from anywhere they are now living and to communicate anonymously if they wish. By incorporating photography and sound-recording as well as storytelling, she hopes it will also provide a resource for younger generations. Dr Sasaki explains: “This project aims to provide a place where (evacuees) can feel at home and securely able to express their own voice. It also aims to pass local stories to the next generation by introducing artistic expression.”

Hotline Namie

There are three strands to the project so far: a telephone hotline, a digital calendar and a digital archiving platform. ‘Hotline Namie’ links evacuees in a temporary housing centre with a programmed machine in Namie. People can listen to sounds from Namie, for example of the sea, or speak to Namie by leaving a message. In three days, 26 residents used the telephone and for some it was a near-religious experience. As Dr Sasaki says: “Accessing Namie via a phone line has a similar function as visiting a Shinto shrine to worship a deity and make a wish as in Japanese tradition. Having conversations with deceased people or sharing mundane experiences,s a secretive and personal act.”

One evacuee left the following message: “Dear deceased friends, can you hear me? What an incident it was. I never thought such a thing would happen. Now, we are all isolated or stolen by the Tsunami…. Wishing we can visit our ancestors’ graves forever, please watch over us.”

Digital calendar

Dr Sasaki has also created an online calendar, ‘NamieHours’, onto which people can upload photographs inspired by memories of their hometown every day. As before, they can do this anonymously if they wish. Workshops were first held to help evacuees improve their photographic skills. They were also encouraged to think of their images as Haiku – traditional Japanese poems which describe aspects of the physical world in a way that symbolises the poet’s feelings.

People can upload text to explain why an image is meaningful for them, perhaps because of the date or season. For example, one evacuee uploaded photographs of rice planting and explained how he used to help neighbours: “We used horses to puddle the field. Weeding the field was the tough one.”

On other occasions people might upload text, for which Dr Sasaki has created accompanying images. For example, she uploaded the image of a broken plate to illustrate this moving testimony: “Sounds of something cracking at midnight. I figured out why as I grew up. It’s hard to be a daughter-in-law in a big farmer’s house.”

Animating memories

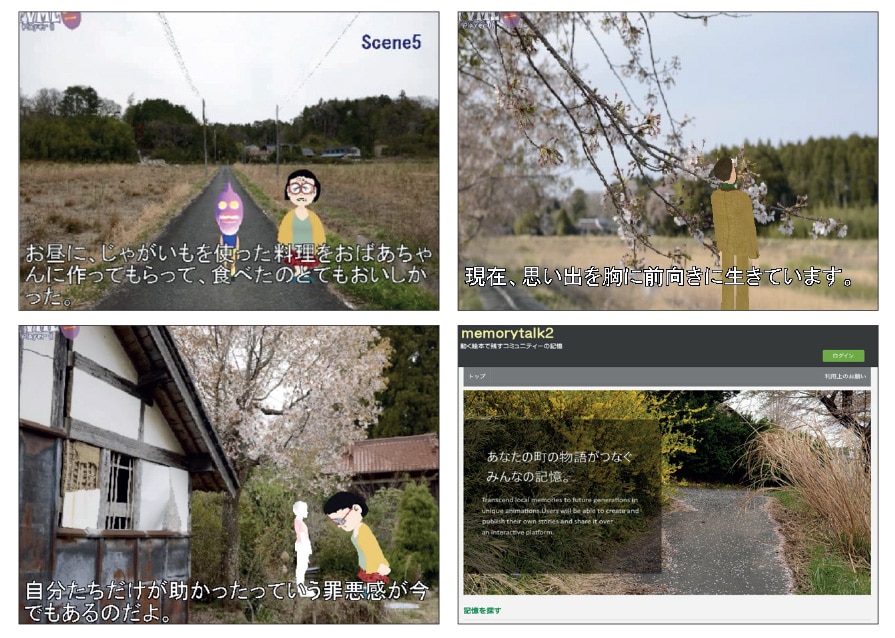

The third aspect of the project is ‘Memorytalk’, a social networking platform that allows users to archive text, videos and photographs about Namie. The aim is to create a virtual community which allows users to record their own memories which is hoped will stimulate communication between users. Evacuees can also turn their stories into animations through the development of online tools.

This project aims to provide a place where evacuees feel at home and are securely able to express their own voice.

Users first choose one of 84 characters or ‘avatars’ to be their online narrator, which allows them to be anonymous. They also choose a background image and soundtrack against which their story is told. This can either be a monologue or a dialogue with other avatars. They can make their avatars move by choosing gestures, for example jumping, bowing or smiling and when all inputs are selected, the animation plays at the touch of a button.

Evacuees of Namie are relocated all over Japan, yet this project hopes to bring them home virtually by sharing and participating.

Dr Sasaki hopes the introduction of animation into storytelling will result in Memorytalk succeeding where other archive projects have failed, for example through being expensive to maintain or having declining user numbers. Other sites have also been aimed at learning lessons from people’s experience to help prevent similar disasters in the future. Unlike Memorytalk, they have not been about helping evacuees to make sense of their personal experience.

Dr Sasaki said: “Since Memorytalk is an SNS-based (social network system) platform users can communicate with each other online by commenting on the uploaded content. This takes the process beyond simply generating various life stories. Keeping communication online might also bring users back to the site regularly, which can help to keep the archive alive.”

Reconnection

Dr Sasaki’s project is ongoing, and its success has yet to be reviewed. However, the quality of communication in the new virtual community is impressive and an archive is being built to help future generations know more about Namie’s past. Above all Dr Sasaki hopes her work will not only help to revitalise Namie by reconnecting evacuees with their hometown, but that it will also help people get in touch with their inner selves.

Dr Sasaki says: “Evacuees are relocated all over Japan, yet this project hopes to bring them home virtually by sharing and participating. The entries are based on people’s memories of daily life and help to preserve local culture, helping people to remember Namie well.”

Personal Response

Many of the elderly Fukushima survivors may not be used to the digital online world that younger people now take for granted. How have they reacted to going online and, for example, using avatars and animations to tell their stories?

<> It is true that elderly survivors have difficulty using IT. This is why I created the Hotline Namie, which allowed elderly evacuees to use the old fashioned telephone. I use different media for different target groups. For example, I tried the Memorytalk, the animation app, to target teenagers. Memorytalk involves a lot of steps to upload the entries. It is not user-friendly for elderly people.

However, the town of Namie distributed tablet devices, such as ipads, to each household. The city also tries to communicate with distant families. Elderly people are gradually getting used to IT devices and the digital calendar was very easy for even them to use.