Omnipresent microplastic

Microplastics have invaded every crevice, nook, and cranny on our planet and they are here to stay. Remember that plastic bottle you threw away back in the ‘80s? Well, it hasn’t disappeared – instead, it has fragmented into a million tiny pieces, which are now swimming in every ocean, infiltrating the soil in farms around the world, and even circulating in the air we breathe. These annoying little particles have been found everywhere from the top of Mount Everest to the bottom of the Mariana Trench.

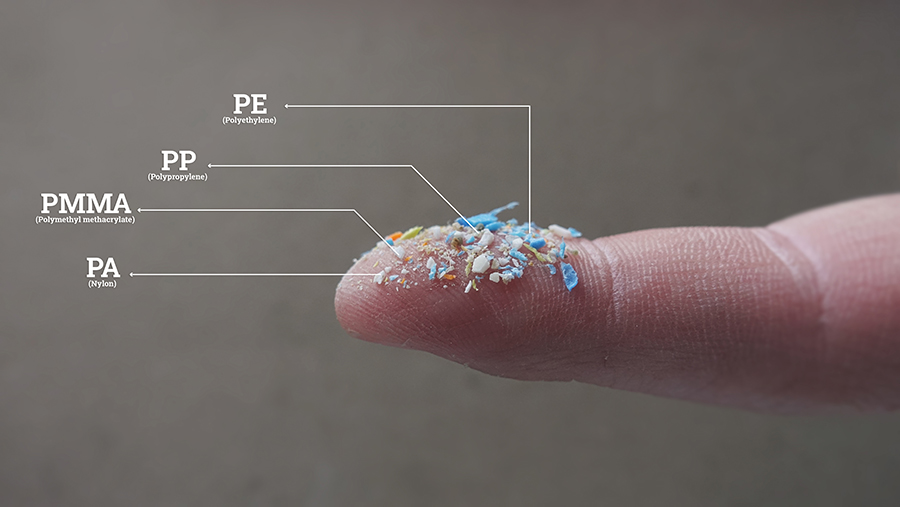

The term ‘microplastics’ includes all bits of plastic which measure less than five millimetres. They can be intentionally made this size and include the microbeads used in personal care products such as exfoliants. Thankfully, these are now banned in many countries around the world, but we still have to deal with the millions already dumped in the water.

However, by far the vast majority of microplastics come from discarded items that float around in the oceans or are dumped into landfills. Over time, these products get fragmented into smaller and smaller particles that seem to have the power to get everywhere.

After all, we’ve read the news about microplastics detected in drinking water, salt, and even beer. The crucial question is: how did they get there? This is supposedly an item we throw away, but somehow it keeps coming back into our lives. And exposure is only likely to rise, as plastic production is still going up. This expected increase has prompted urgent calls for research into the effects of these microplastics and, more importantly, ways to get rid of them.

They’re in the water

It’s estimated there are over eight million tonnes of plastic waste floating around in the oceans. How much of that will end up as microplastics is anybody’s guess. Most studies only dare to survey what’s close to the surface, and that alone can add up to over 125 trillion particles. And this value doesn’t even include microplastics polluting locations on land, or already lodged inside animals. Even if we managed to magically stop producing plastics tomorrow, microplastics would continue to pile up for years just from rubbish already accumulated in the sea.

With this amount of microplastic around them, most aquatic species are inevitably going to ingest some. Microplastics are on the menu for many fish, coral, marine birds, invertebrates, such as oysters and mussels, and even marine mammals such as dolphins, seals, and whales.

A recent study found microplastics in the stomachs of three out of every four deep-water fish caught in the Atlantic. This is definitely not good news: many of these fish represent a valuable food source for other marine species such as tuna, swordfish, dolphins, and sea birds. This is potentially the fastest way to contaminate the rest of the food chain, including humans.

In addition, these deep-water fish typically live at depths of around 200–1,000m but swim to the surface at night to feed. Under normal circumstances, this movement up and down is vital to transport nutrients from the surface to the deep sea. However, these meals now have a side dish of microplastics, spreading pollution to deeper waters and affecting species that wouldn’t normally encounter them.

It’s estimated there are over eight million tonnes of plastic waste floating around in the oceans.

They’re on land

Research is very black and white when it comes to microplastics in our oceans: they’re everywhere and can be very dangerous for marine and coastal environments. Yet, microplastic pollution on dry land is much worse than on water – up to 20 times more in some areas – but somehow this has received less attention.

There are many ways for microplastics to jump from their ocean environment to a terrestrial location, miles away from any water. Sewage is likely the most significant contributor, as microplastics are virtually impossible to remove and over 80% hang around in the sludge. If this sludge is used as fertiliser in farming areas, it can spread thousands of tonnes of microplastics.

Microplastics have also been buried in the sand on many beaches, presumably carried by ocean currents. Studies suggest this could be particularly harmful to animals living between water and land. Turtles are one example. Researchers expect microplastics to severely affect these reptiles, with lower hatching rates and even changes in the ratio of female and male turtle hatchlings.

Microplastics can escape from contaminated waters carried by flying insects. Worryingly, when scientists fed microplastics to mosquito larvae, the particles stayed inside the animals as they grew into flying adults. Birds, reptiles, bats, and spiders are some of the species that feed on insects, which means they’re also feeding on microplastics. And the problem extends higher up the food chain, with microplastics now found in many birds of prey, including hawks, ospreys, and owls.

For decades, researchers believed that plants at least were safe from this plastic invasion. After all, microplastics are too large to be absorbed through the roots. However, it turns out that’s not exactly the case. Spots where emerging roots are developing seem to be extra permeable, and microplastics can sneak in from the surrounding soil and water and then be transported to other parts of the plant.

This could mean even the vegetables we eat can be contaminated with microplastics. What’s more, if microplastics get into crops, they’re also getting into meat and dairy. Inevitably, this raises serious concerns about using sewage sludge or wastewater discharge to water crops for human consumption.

They’re in the air

The reality is, nothing is safe from microplastics anymore. And it’s not just water and land. Researchers have known about global dust for decades, but only recently found out that there’s microplastic in this dust. While large and heavy particles don’t travel far, lightweight tiny plastic can stay aloft for long distances, staying high up in the atmospheric dust.

Roads are a massive contributor, with the constant turning of tyres tossing tiny pieces into the air. Much of this dust also comes from the oceans, where floating plastic slowly degrades, and particles are hurled into the atmosphere. Finally – but certainly not surprisingly – farming is another important source, with microplastics coming from the use of wastewater or sewage sludge. Windy situations only make this problem worse.

Then, once plastic reaches the atmosphere, it can stay airborne for days, which is more than enough time to travel halfway around the world. Microplastics will eventually fall back in the ocean to be eaten by a fish or on dry land to be absorbed by a plant. Some of this dust falls back during dry conditions, but most of it is dragged down in precipitation. This plastic rain may give you flashbacks to the acid rain that fell over most of Europe and North America in the ‘60s and ‘70s, but it’s more pervasive and difficult to eliminate.

Whatever action we take now, the microplastic cycle is set to continue for centuries. It’s sobering to wonder where we’re going to find it next.

Alex Reis is a freelance science writer based in the UK

www.alexreis.science