The child deficit and the changing value of children in Asia

Philip Morrison, Professor Emeritus at Victoria University of Wellington in New Zealand, has been conducting research to understand whether changing values may be leading to changing family size decisions that are associated with declining fertility rates across Asia. His findings have been published as chapter 14: ‘The child deficit and the changing value of children in Asia’ in Poot & Roskruge (eds) (2020), Population change and impacts in Asia and the Pacific.

In most Asian countries, average family size has more than halved over the past six decades. This decline has been most evident in East Asia where fertility decline is closely linked to the decisions women are making about marriage and motherhood. These decisions include whether to marry, when to marry, when to have children and how many children to bear. In these regions of Asia, these decisions have been influenced by widening access women now have to further education and employment in the formal sector.

Within other regions of Asia – mainly Central and South Asia – women’s decisions about marriage and motherhood do not seem to be having the same influence on the fertility rate. Yet in these countries, there has also been a marked decrease in average family size. Prof Morrison set out to investigate what other factors might be driving the decline in fertility rates in Asia. He writes: “By middle age, individuals living in Asia will realise far fewer children than they wanted as young adults.”

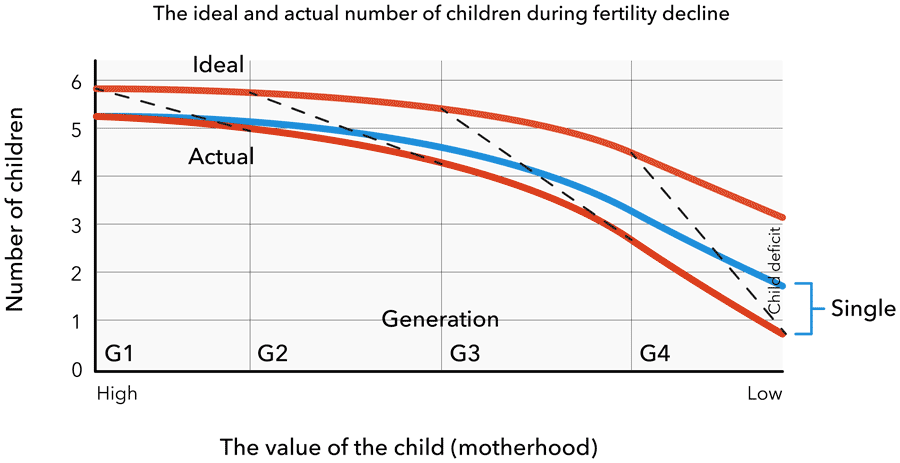

Internal motivational drivers, such as the changing value woman are placing on motherhood and raising a child, may also drive decisions about whether to have children and how many children to raise. Prof Morrison argues that values regarding ideal family size are internalised by children at a young age. These ideals often reflect the number of siblings within a household in which a child is raised. What is more, they are likely to change far more slowly than external constraints which impact on family size. Parents may therefore end up with a gap in the number of children they initially expected to have (their ideal family size) and the number of children they eventually raise (their actual or realised family size). This gap between the ideal and the actual is what Prof Morrison refers to as the ‘child deficit’.

The data reflects a steady change over time in women’s views of the role of motherhood within their lives.

Prof Morrison set out to explore the presence of the ‘child deficit’ in Asia using data from the World Values Survey (www.worldvaluessurvey.org). This survey dates back to 1981 and gathers information on the changing values held by people in a wide range of countries. The survey data is compiled by an international network of social scientists. Using these data from 1990-2010, Prof Morrison analysed changes in values in two Asian countries where the relevant questions were repeated: Japan and South Korea. Women between the ages of 15 years and 90 years of age were asked to respond to the statement that “A woman has to have children to be fulfilled”. The response options were either “Not necessary” or “Needs children”. The results showed a drop over time in the percentage of women agreeing with the statement. In the data collected between 1990 and 1994, a total of 71.5 percent of women sampled in Japan considered children to be essential for their fulfilment. By the next decade, this figure had dropped to 64.9 percent of women. Similar results applied to South Korea. Although limited to two Asian countries, these results reflect a steady change over time in these women’s views of the role of motherhood within their lives. Prof Morrison concludes that “in an age of planned parenthood most parents now weigh up the costs and returns before deciding on having an additional child”.

Ideal and actual number of children

In order to obtain an estimate of the child deficit, Prof Morrison ran two sets of regression models, one to estimate the probability of each ideal family size and the other to estimate the probability of each realised family size. The average predicted probability from the first regression for each country was subtracted from the predicted probability from the second regression and related to the country’s total fertility rate. The result showed that the estimated child deficit rose as a country’s average family size declined.

The first set of regressions was designed to estimate the probability a young woman would prefer not to have children, another to estimate one child as the ideal and so forth. The equation used as its arguments the response to the above value question, the number of children the woman already had, her age (between 20 and 35 years), whether she held a tertiary qualification or not, whether she was employed and which of the 14 country-waves she was sampled in. This last variable, the country, had a profound influence on the ideal as did the number of children already in the family. When it came to those respondents whose ideal extended to three or more children, Prof Morrison found very low probabilities in the high-fertility countries of Bangladesh and India but surprisingly high probabilities in low-fertility countries such as Japan, South Korea and Singapore. The value the woman attached to motherhood had a profound influence on wanting at least one child (controlling for the other variables in the model) but had a decreasing influence as the ideal number fell. In other words, the value of the child, as defined above, had a rapidly diminishing influence on the ideal number of children beyond one.

While young adults may set out with certain expectations about their ideal family size, circumstances and environmental constraints result in young people compromising these expectations later in the harsh reality of day.

The second set of regressions applied to middle-aged women produced estimates of the probability of having raised no children, one child and so on. What is particularly interesting is the diminished role that the value of the child played when it came to explaining who actually had children as opposed to simply expressing voicing an ideal number. A noticeable difference from the case of the ideal number is the role played by tertiary education on the actual number. Holding a tertiary degree did not influence young adult’s ideal number of children but it did have a clear negative effect in realising successive family sizes. Similarly, in the case of employment, middle-aged women who were employed reported fewer children. This feature was not observed when it came to young women espousing their ideal family size.

Fertility declines: values or constraints?

Decisions about fertility require trade-offs with positive and negative outcomes for individuals and the society. While young adults may set out with certain expectations about their ideal family size, circumstances and environmental constraints result in couples compromising these expectations later in the harsh reality of day. These factors include, amongst others, the urban environment, standard of living, income, and opportunities to realise their expectations and potential as parents.

The very presence of a high child deficit in low-fertility countries suggests a built-in preference for larger family size which contemporary living arrangements are unable to satisfy – linked as they are to urban housing costs, deep-seated labour market institutions and priorities which many government find hard to address. The interaction between the values reflected in ideal family size and their realisation as actual family size is also important for what it implies for future population growth. The contemporary challenge in developing pro-natalist policy will be to identify those levers that will allow the women (and men) to realise those family sizes that approximate more closely their ideal.

Personal Response

How is the child deficit likely to impact on women, children, societies and regions with ultra-low fertility rates?

<> The nature of the impact depends on whether one is addressing the individual, the family or the society as a whole. The expanding body of research on the impact of children on the well-being of adults, both fathers and mothers, shows marked variation depending on the stage of parenthood, especially the age and number of children. My research on the child deficit shows that the response to the value of the child question has the most impact on the decision to have the first child but carries diminishing weight with the second and subsequent children. The literature in turn shows that the well-being impact of the child varies depending on the demands they place, along with other life stage considerations, on the parents themselves. The returns to childbearing change with the age of the child, the age of the parent and grandparent as well as the socio-economic circumstances of the family.

The impact of the child deficit on the society as a whole has not been widely studied nor have its psychological, material and social relationship consequences for parents been widely considered. Of particular interest is how it informs the development of pro-natalist policies in countries facing falling marriage rates, smaller families and an aging population. A major question is the degree to which governments can reduce the child deficit by changing the ideal and/or realised family size of successive generations and the degree to which those changes will have identifiable well-being consequences for the individual and the family.