Exploring the impact of trust and world view on Indigenous patients’ engagement in shared decision making

The relationship between Indigenous people (i.e. First Nations, Métis and Inuit) and Europeans living in Canada has continuously evolved over time, following a number of peace and friendship treaties, commercial agreements, military alliances, and other pacts between them. In the late 1800s, however, a series of government regulations related to Indigenous identity sparked tensions and contributed to the Indigenous population’s general distrust of institutions, including healthcare providers.

In Canada, Indigenous peoples are diagnosed with common cancers at a higher rate. They are also more likely to be diagnosed at a later stage and have lower chances of surviving the disease than non-Indigenous people. This could partly be due to their distrust of institutions and their general world view, which can differ greatly from that of non-Indigenous people.

Dr Gary Groot and other researchers at the University of Saskatchewan have been conducting extensive research aimed at understanding how trust and world view affect the extent to which Indigenous populations in Canada engage with the healthcare system and with what is known as shared decision making (SDM). Their work relied heavily on the contribution of Indigenous patient partners and Indigenous scholars, who collaborated in several aspects of the research.

The model of shared decision making

SDM is a medical decision-making model that became widespread in the late 1980s. This model essentially emphasises the communication and collaboration between healthcare providers, clinicians and patients when making decisions related to a patient’s health, treatment and recovery.

The SDM model consists of several key elements, which it identifies as essential for a constructive decision-making process. For instance, it suggests that shared decision making should at the very least involve a patient and his/her physician and that it should promote a balanced relationship between these parties. Moreover, this process should be based on an open exchange of information (e.g. touching on a patients’ values and preferences) and the discussion of possible treatment options, leading to a decision that parties mutually agree on.

The SDM model has proved to be particularly valuable in situations where a patient can choose between numerous treatment options, for instance after he/she is diagnosed with cancer. In fact, cancer diagnoses generally require patients to make important decisions quickly, often with only a limited amount of information available to them.

In their recent studies, Dr Groot and his colleagues set out to better understand some of the factors that might influence whether Indigenous patients engage in SDM with their doctors and local healthcare providers.

Dr Groot developed a realist synthesis of shared decision making between Indigenous patients and healthcare providers.

Which factors influence the decisions of Indigenous peoples?

“Indigenous peoples have been exposed to colonial forces that have affected their levels of trust with institutions, and, at the same time, they have a world view that tends to be distinct from that of non-Indigenous people”, Dr Groot explained. “We built on our theory for SDM to understand how trust and world view might work differently for Indigenous patients when engaging in SDM.”

Dr Groot and their colleagues wanted to gain a better understanding of how trust and world view perceptions influenced the engagement of Indigenous patients in health-related SDM. To do this, they focused on elements that could partly explain the differences in SDM engagement between Indigenous and non-Indigenous patients.

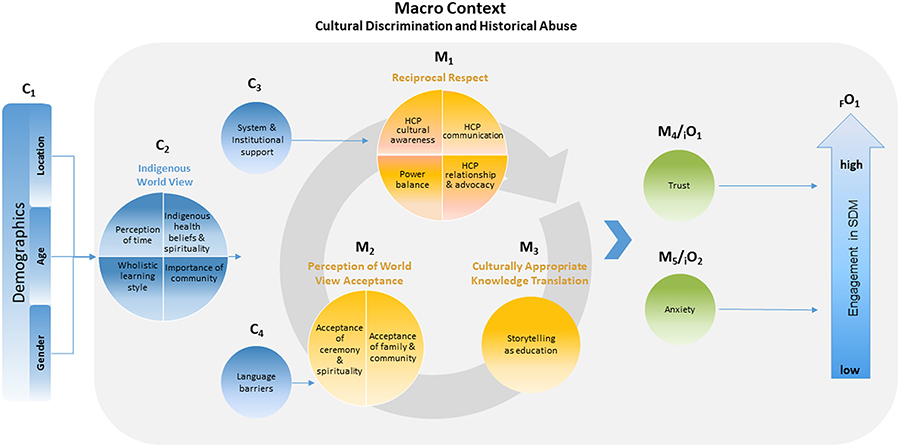

“In a healthcare consultation involving Indigenous patients, we wanted to explore for whom, why, and in what situations trust and perceptions of world view influence patient engagement to achieve SDM”, Dr Groot said. “To understand these causal relationships, contexts (C), mechanisms (M), and outcomes (O) are extracted from existing literature and configured into realist explanations of why, how, and for whom an outcome occurs (i.e. if processes appear (M) in the conditions (C), then a given outcome (O) will result).”

Reviewing previous observations

In a study carried out in 2019, Dr Groot and his colleagues screened research data extracted from a number of online sources, including Medline, CINAHL, and the University of Saskatchewan’s iPortal. This included a total of 90 documents, 53 of which were peer-reviewed papers and 37 of which were based on grey literature (i.e. research material produced by organisations outside of traditional publishing and distribution channels).

In these documents, the researchers were able to identify 518 context-mechanism-outcome (CMO) relationships that could help to shed light on the factors influencing Indigenous patients’ engagement in SDM processes. They then synthesised these 518 relationships into 21 CMO configurations, which could inform the development of a revised theory of SDM.

The contexts identified by the researchers included patient demographics, the Indigenous world view, the Canadian healthcare system, institutional support offered to Indigenous communities, language barriers, and the abuse or discrimination experienced by Indigenous populations throughout history.

Mechanisms involved in SDM, on the other hand, included reciprocal respect between patients and healthcare providers, a patient’s perception of whether his/her world views are accepted, and culturally appropriate translations of medical knowledge/information. These mechanisms were found to impact the level of trust in healthcare providers and the anxiety experienced by Indigenous patients, which ultimately determined their level of engagement in SDM.

A more realistic SDM theory

Dr Groot and his colleagues used the CMO configurations they identified to develop a realist synthesis of SDM between Indigenous patients and healthcare providers. Using this synthesis, they then developed a programme theory of SDM that outlines a number of core contexts and mechanisms, with a single outcome. This theory could help to improve the healthcare experiences and clinical outcomes of Indigenous people in Canada.

The contexts delineated by the researchers’ theory are the pre-existing relationship between a patient and healthcare providers/institutions, the difficulty of the decisions they are asked to make, and the support received from the healthcare system.

The mechanisms, on the other hand, include their anxiety, trust, perception of the other party’s competence, perception of time, self-efficacy, world view, perception of capacity of external support, and the recognition of the decision to be made. Finally, the outcome is a patient’s level of engagement in the SDM process.

Indigenous patients’ trust in healthcare providers and their world view can influence their cancer journeys in some unique and complex ways.

Factors influencing Indigenous people’s cancer care decisions

In another recent study, Dr Groot and his colleagues investigated treatment decision-making processes among Indigenous patients diagnosed with cancer in rural and remote areas in Alberta and Saskatchewan. To do this, they analysed clinical data related to 17 Indigenous cancer patients and discussed it with the patients in question, to ensure that they accurately interpreted their decision-making processes. Transcripts of the interviews with the patients were analysed using a narrative method (i.e. presenting the data in a story-like format).

Dr Groot and his colleagues created eight vignettes summarising some of the main aspects involved in the process, namely being strong for family, family support, strength and independence, denial and not wanting to know about the disease, fear-based decision-making, finding the blessing, the patient’s spiritual journey, and traditional medicine. This narrative analysis allowed the researchers to unveil similarities and differences in how Indigenous people with cancer decide what treatment to choose.

As part of another study published last year Dr Groot and his colleagues interviewed 14 Indigenous patients diagnosed with cancer utilising a traditional approach to group discussions known as the ‘sharing circle’. The patients were asked to share aspects of their cancer journeys and their experiences while sitting in a ‘sharing circle’.

The researchers identified two recurring meta themes in the experiences shared by these patients, namely trust and world view. Trust was represented by mistrust in Western diagnoses and treatments, as well as the protection of Indigenous medicine and expertise. The patients’ world views, on the other hand, were characterised by their willingness to combine the best of Indigenous and Western worlds, their spiritual beliefs, the feeling that they should be strong for their family, and their acquaintance with Indigenous survivors.

Towards a greater engagement of Indigenous patients in SDM

Overall, the research carried out by Dr Groot and his colleagues suggests that Indigenous patients’ trust in healthcare providers and their world view can influence their cancer journeys in unique and complex ways.

The researchers found that while some Indigenous patients only trusted traditional Indigenous medicine, others also sought the support of Western healthcare providers. These findings highlight the possible benefits of healthcare systems that allow Indigenous patients to access both traditional and Western medicine.

The collaboration of Indigenous patient partners was of vital importance for these researchers’ work, as it is what ultimately allowed them to better understand the factors underpinning Indigenous experiences with healthcare services. “Without their support and guidance, the initial narrative study, the sharing circle, and the trust/world piece could not have happened”, Dr Groot says.

In the future, the observations gathered by Dr Groot and his research group and the new programme theory they devised could inform the work of both clinicians and policymakers in Canada, allowing them to devise strategies to improve the healthcare services offered to Indigenous peoples and to encourage them to make the best use of these services.

Personal Response

What inspired you to conduct this research?

<> Caring for cancer patients requires excellent technical, cognitive and social skills, including the ability to understand a given patient’s treatment goals and explaining the risks and benefits of the options available to them. What began as a journey to improve my person communication skills with Indigenous cancer patients quickly evolved into an understanding that engaging Indigenous patients in a shared decision-making process is a complex challenge for many healthcare workers deserving of a more comprehensive and collaborative exploration with Indigenous patients and Indigenous scholars. When the opportunity to research this topic presented itself, I gratefully took advantage of it.