Teaching words and how words work

Words help to shape children’s development and existence. Written and spoken, they are the tools with which they engage with education and society, and it’s through them that children come to understand and negotiate the physical and mental spaces they inhabit.

How best then, do we teach words? American educator and researcher Elfrieda “Freddy” Hiebert is an acknowledged expert on how vocabulary acquisition can be fostered in schools. She has also founded a not-for-profit corporation and website which offers free, downloadable resources to help in the classroom. Her latest book “Teaching Words and How Words Work” offers guidance on how teachers can use these materials to help students increase their vocabulary and understanding.

Dr Hiebert proposes a transformation in how vocabulary is taught and learned in schools. Although based on the American school experience, it is relevant to teachers of English around the world. What makes Dr Hiebert’s approach particularly interesting is that it is based on substantial research using digital technologies to assess vast quantities of data and carry out complex analysis of texts as never before. Dr Hiebert explains: “Scholars are no longer limited by the tedious task of hand counting words. Now the numbers, kinds and distributions of words from millions of texts can be established in a nanosecond.”

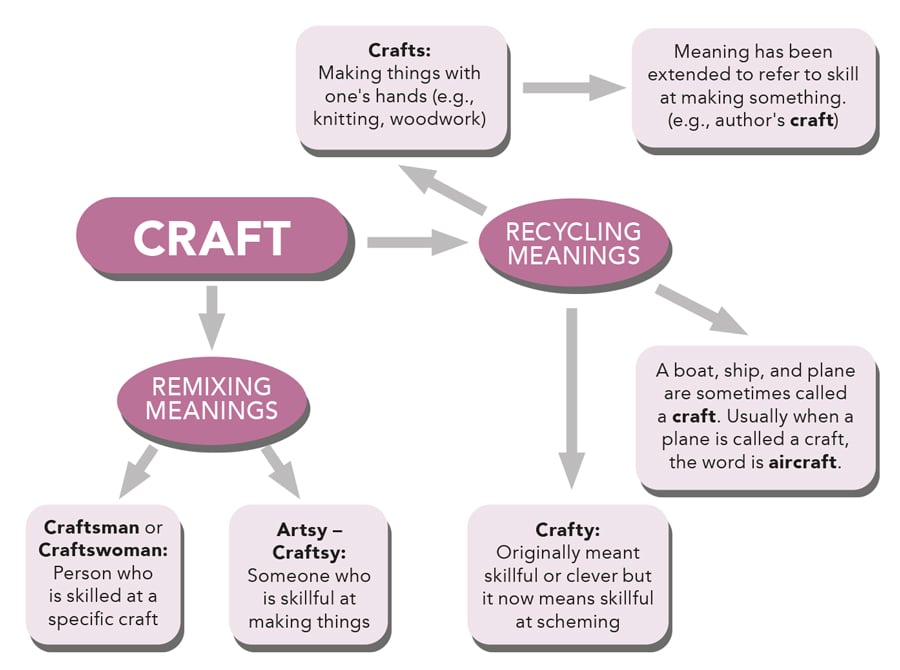

As a result of her research, Dr Hiebert’s new approach to vocabulary learning has a strong evidence base. The method of vocabulary instruction she proposes is generative, in that it teaches children strategies to help them understand, or “generate”, the meaning of unfamiliar words. It also puts forward a relationship-based approach to vocabulary acquisition based on the understanding that words are best learned in groups of related words rather than in isolation from one another.

The challenge

The importance of vocabulary instruction in schools and its relationship to learning and knowledge acquisition cannot be over-estimated, particularly in the early years. As Dr Hiebert explains: “The breadth and depth of people’s vocabularies influence their life experiences.”

Children acquire knowledge through texts, but texts also open the door to new concepts and experiences. Dr Hiebert adds: “The relationship between vocabulary and texts is reciprocal. Familiarity with the vocabulary of a text supports comprehension, while simultaneously texts are a primary source for gaining new vocabulary.” However, deciding which words to teach, is no easy task given that the Oxford English Dictionary contains more than 600,000 entries.

Traditional approach

In the American school curriculum vocabulary instruction has for decades focused on teaching six to eight new words from a target text each week. Dr Hiebert cites the example of a text “Annie’s Gifts”, aimed at eight to nine-year-olds, about an apparently non-musical child’s experience of living in a musical family.

The text contains 45 probably unfamiliar words, from which ‘except’, ‘stomped’, ‘entertain’, ‘carefree’, ‘sipped’, and ‘screeching’ form the basis of that week’s vocabulary learning. Dr Hiebert says it’s unclear why these words have been chosen, not least as words like ‘stomped’, ‘sipped’ and ‘screeching’ can be easily explained by synonyms or demonstration. She is equally puzzled why other words in the story like ‘melodious’ and ‘rhythm’ are overlooked. However, her main concerns are the speed and narrowness of this approach to new vocabulary acquisition, not least that words are taught in isolation from one another. Dr Hiebert clarifies: “If this pace of targeting six to eight words per week is maintained across the grades, students will be directly taught about 3,500 words during their school careers. Such instruction barely skims the surface of English vocabulary.”

The breadth and depth of people’s vocabularies influence their

life experiences.

Digital analysis

In her extensive research, Dr Hiebert used digital technology to analyse thousands of texts used in schools. In particular, she looked at words’ frequency, meaning, length and usage, as well as their overall complexity. She explains: “Digital programmes make it possible to instantaneously establish numerous features of the words in a text; establishing the frequency of words at different grade levels and in different kinds of texts can be accomplished with a click of a button.

“Similarly, once an algorithm has been identified, words with similar meanings can be clustered. Words that may not be familiar to students at a specific age can be specified. Words also can be organised by root words, making it possible to identify rich groups of words with a shared meaning.”

Research findings

Among the insights gained, Dr Hiebert found that the 20,000 words most frequently used in school texts can be broken down to around 5,500 families of words from the same root, for example, improve, improves, improving, improvement, unimproved. On average, these word families accounted for 95% of the language of school texts.

Deeper analysis showed that the root words of around 1,000 of these 5,500 families of words are likely to have already entered children’s vocabularies by the time they are five, reducing the number of words needing o be taught in school.

The findings also revealed that 1,250 of these 5,500 families of words represent concrete rather than abstract words. Concrete words are learned more easily. For example, a concrete word such as ‘frog’ can be quickly understood by using a picture, whereas an abstract concept such as ‘fate’ is more difficult. Taking concrete words out of the equation, it leaves 3,250 families of words to be learned. However, 600 of these word families are unlikely to appear in school texts until children are aged 12 or older.

Dr Hiebert’s research also looked at the approximately 5% of words used in school texts which are not covered by word families. Although they account for around 80% of all words in English, many are proper names and their use is rare. Readers can expect to encounter around three of these rare words in every 100 words of text.

As a result of her research Dr Hiebert believes that the core vocabulary upon which teachers should concentrate throughout a student’s school career is around 2,500 families of words.

The 20,000 most frequently used words can be broken down to around 5,500 families of words from the same root.

New approach

Dr Hiebert has based her proposals for a new approach to reading instruction on her research findings. Not only has she developed teaching strategies to support her views, she has also made numerous texts and teaching resources freely available online.

The approach she expounds represents a major change in how teachers think about words. However, rather than advocating substantial changes to the curriculum, Dr Hiebert believes that small changes can achieve big results.

For example, still using the text “Annie’s Gifts” as a starting point for discussion, Dr Hiebert suggests that teachers could encourage students to expand the word ‘music’ into a “semantic map”. In this way teachers can help students to explore such things as the different sounds of music and how it makes people move and feel, the instruments that can be played and the events at which it is heard, as well as features such as melody and rhythm.

In another lesson teachers could ask students to look at the different meanings of associated words, for example ‘embarrassed’, ‘embarrassingly’ and ‘embarrassment’, and ‘melody’, ‘melodious’ and ‘melodiously’. They could then move on to look at figurative language and explore the metaphors used to indicate how Annie’s piano-playing sounds, for example, “like the honking of a diesel truck”.

Conclusion

Dr Hiebert’s new evidence-based approach to vocabulary instruction in schools represents a major shift in educational perspective. Her approach is informed by the substantial number crunching made possible by the digital revolution. However, her aim is about more than increasing the number of words students learn.

As Dr Hiebert explains: “To paraphrase the adage about the effects of teaching people to fish, teaching students a handful of the rare words in a single text may aid them in comprehending that text, but without knowledge about relationships across words, students will not be equipped to deal with unknown words in new texts.

“What is essential is to keep in mind that students’ learning vocabulary is not in itself the end goal. Instruction in the relationships among words and how words work always occurs in the service of supporting students in gaining knowledge about the world in which they live.”

For more information about Dr Hiebert’s research and the TextProject, visit www.textproject.org

Personal Response

Your work is primarily aimed at teachers of children who use English as their first language. How might it also be helpful to teachers of English as a foreign language?

<> The evidence-based vocabulary approach is as critical if not more so—for those learning English as a second or third language as it is for native English speakers. The complex orthography of English means that it can be a challenging language to learn. When instruction emphasises the most prolific root words in written and oral language, English learners gain the tools to be proficient language users. Skill with prominent root words also gives English learners anchors for integrating many related words into their vocabularies. A focus on core vocabulary and the networks represented by these words gives English learners a solid foundation for success.