When Narratives Collide: The Fundamentals of Islamic Fundamentalism

Shock swept the world in 2015 when images surfaced showing Islamic State’s (IS) demolition of ancient ruins in Hatra. The destructive act was widely portrayed as a “return of the barbarians”, reflecting the West’s view of itself as curator of World Heritage. Such an understanding of heritage as universal and pluralistic is countered by a fundamentalist narrative, which exclusively recognises the legacy of Islam. From this perspective, historical artefacts are forbidden if they predate or otherwise deviate from the principles of the Islamic founding age. Baudouin Dupret at the French National Centre for Scientific Research delves deep into this collision between concepts of heritage and the narratives that follow. His research uncovers how both outlooks have developed in a conflicting yet interdependent manner, and continue to underlie the ideology, media, and action of Jihadi and Western parties. The investigation was funded by Les Afriques dans le Monde (LAM), an international leading research centre looking at the impact of globalisation on African societies. LAM’s interdisciplinary research teams and partnerships include political scientists, economists, lawyers, and literary experts, forming a wide lens through which to view the intricacies of African life.

The heritage of ‘heritage’

At its core, heritage means receiving something from ancestors, although particular concepts of heritage vary across cultures. For example, the French formulation of ‘patrimoine’ specifies the inheritance of wealth from and by the family, while the English ‘heritage’ and Arabic ‘turâth’ indicate the process of inheritance itself. However, in every variation, heritage depends on a social and cultural order to provide its meaning. In other words, policies, attitudes, and practices are required to construct a ‘heritage’. After all, old monuments have existed before the heritage label, but the specific social phenomenon of heritage was not set in motion until the category was conceived.

At its core, heritage means receiving something from ancestors, although particular concepts of heritage vary across cultures.

Heritage offers a set of meanings that frame and influence how possessions are passed across generations, securing a group’s collective identity through time. However, these understandings have evolved. The concept first functioned as a call for people to celebrate their national cultures, and later set out ethical responsibilities for future generations. The values informing these practices have consistently changed, and yet heritage imagines a fixed truth about an ancestral past. Such a tie to ‘authentic’ roots has taken opposing forms. The universalist view rests on the principle that the past, in all its cultural diversity, points to the current Western-inspired global civilisation it was destined to create. This results in an identity where one recognises their true self as a product of a pluralist history. In the fundamentalist model, however, the present is judged against a Prophetic past it can either follow or defy, and an authentic self is gained through strict adherence to such prophecy and the destruction of any deviance.

AP, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ONjPPO7pQKs

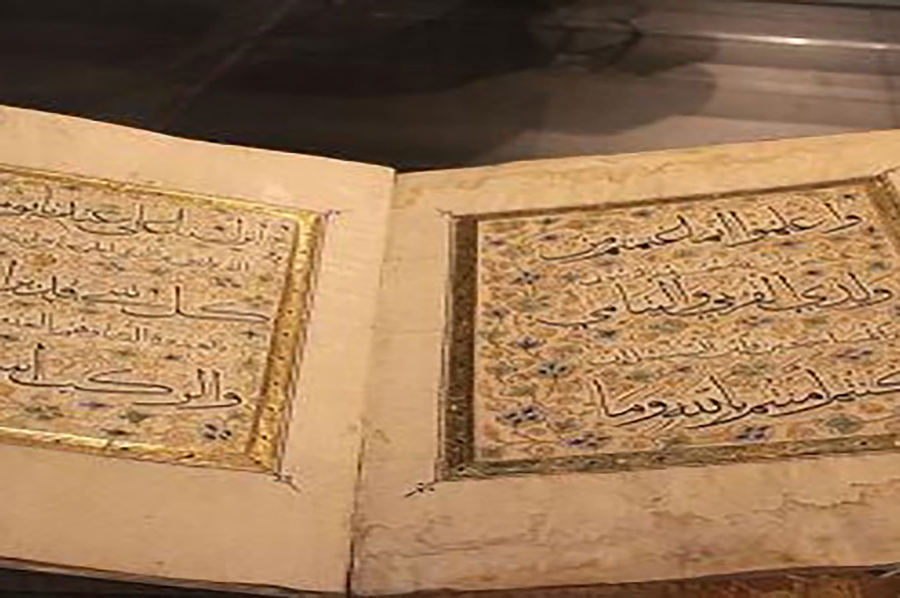

The “Arab Islamic” concept of ‘turâth’ is an adaption of the eighteenth-century Western definition of heritage. The notion was refined by reformers of the Arab renaissance in a period of colonial rule and its aftermath. In such a context, reformers sought to manage the Islamic community’s intellectual heritage by cleansing it from the history of outsiders. Heritage was thus tightly bound around Islam, authenticity, and national identity. From its thirteenth-century origins, turâth has incorporated both material inheritance – the kind a son might acquire from his father – and a spiritual transmission from Creator to human creation. However, when the European administration of fine arts and antiquities began to frame heritage around antique monuments and vestiges, including those in the “Arab Islamic” world, indigenous elites were prompted to emphasise the non-physical aspects of heritage. This historical turn provided the space for values to become the substance of heritage within “Arab Islamic” culture – and with it, a fundamentalist commitment to Islam.

Media matters

In order to study how different concepts of heritage are embedded into media productions, one must first establish what is meant by context. One account of context considers the ‘social structure’, which shapes how media is produced and consumed. The social structure, furthermore, operates outside of what is immediately observable in a given situation. However, the present research engages with context as the locally relevant causes that organise behaviour. Media context, therefore, consists of the way a product’s structure permits and constrains the way it is interpreted. Under this framework, Dupret analysed two videos with contrasting conceptions of heritage. The first video follows the UNESCO promotion of a World Heritage, while the other adheres to a Salafi Jihadist condemnation of historical pluralism.

The “World Heritage” video portrays the city of Hatra as an historical meeting place between East and West, where an array of religions and cultures lived in harmony. The Silk Road is shown to have intersected Hatra, connecting the Northern Iraqi region with the Chinese and Roman Empires via trade. The surprising discovery of a Greek temple is also explored, noting its fusion of Mesopotamian and Mediterranean god concepts and cultures. By contrast, the “Jihadist” video explicitly rejects such a framing of heritage, calling the remains “idols” that “must be smashed”. Such hostility is based on a reading of Qur’ân in which it prohibits any visual representation of human or animal, as well as false gods. Indeed, the script starts with a dedication to God and continues with fighters smashing statues and justifying their actions with reference to the Qur’ân and Islamic history. It concludes with singing a ‘nasheed’ that proclaims the vanishing of falsehood.

The first video depicts Hatra, with its wealth of artefacts from various god beliefs and artistic styles, as a symbol of universalism, multiculturalism, and prosperity. The latter denounces the temple’s visual representation of humans and animals, as well as its religious diversity, as blasphemous worship. The two videos therefore mirror each other in their pluralistic inclusiveness and specified exclusiveness. Moreover, by presenting the World Heritage site of Hatra as a historical tour, the first video uses the ancient city to find an ethical reflection in today’s multicultural tolerance. Meanwhile, the “Smash The Idols” narrative witnesses present-day action by IS as the fulfilment of a sanctified past. As a result, such media invokes the aforementioned collision of narratives. One narrative points the entire pluralist past (via eclectic artefacts) towards its fulfilment in the multicultural present and a Western-inspired global civilisation, while the other acts in the present to carry out the particular principles of Islam.

‘Truth’ And (Ir)reconciliation

By destroying heritage sites, IS seeks to establish ‘tawhîd’ (the oneness of God) and the elimination of ‘shirk’ (associationism) – that is, worship of anything besides God. The wreckage of Palmyra, Nimrud, and Hatra was therefore religiously grounded in Jihadist Salafism. Each attack is designed to eliminate traces of alternative cultures and elevate Islam. Crucially, in addition, IS would be given important media coverage. By striking in diametric opposition to the Western notion of a global civilisation, and calling to mind the provocative example of barbarians, IS could secure widespread attention for its propagandistic performance. The aim of this media exposure is recruitment to Jihad and ultimately Sharî’a, which signifies divine teaching and is often translated as “Islamic law”.

Islamic fundamentalism purports to get to the root of Qur‘ânic texts and rules, but its reading is always a

process of interpretation.

Islamic fundamentalism purports to get to the root of Qur‘ânic texts and rules, but its reading is always a process of interpretation. The scripture contains internal contradictions, room for prioritising one thing over another, and a lack of explicit guidance on many issues. Indeed, IS condemning Hatra’s visual representation of human and animal life is not based on direct Qur’ânic instruction, which merely forbids idolatry. However, literalism does not rely on rational argument. It puts forward the letter of scripture as sufficient for reaching conclusions, even in the face of contradictory passages. It proclaims to be the final word on any subject, appearing more authoritative than arguments over subtleties in the text. Norms are imposed simply because “they are there”, reflecting the belief that divine workings and intentions can never be fully grasped by mere mortals.

The fundamentalist reading of scripture provides, above all, power-conferring rules. In other words, its unwavering commitment is to establish a system of reference, rather than the details of legal life. This system of reference demarcates the “authentic Muslims” belonging to “true Islam” from all others and is communicated through the aforementioned media products and political action. Such a delineation echoes the colonial and post-colonial derivation of the Arab Islamic concept of heritage, which sought to cleanse the Islamic community’s intellectual heritage from the history of outsiders. Indeed, from such an intertwined history, the two opposing notions of heritage share an identical conceptual structure. Both frameworks see heritage as transmission across generations, collective ownership defining a collective identity, a universal claim, the recognition of an authentic self, and something to be preserved. In a mirror game, therefore, the Western narrative of inclusive universalism is replaced by the exclusive universalism of fundamentalist Islam. These mirror representations do not simply co-exist but also nurture each other, amplifying the antagonism. As a result, the two camps cannot alter the content of their opposition to escape the impasse, since the mirror game is designed to maintain it. Instead, the conditions that prompt the mirror game must be confronted.

Personal Response

What inspired you to conduct this research?

Heritage is universally celebrated. But what does this notion cover? Is it possible to understand what it means in traditions other than the one that predominates? And are the different meanings independent of each other or do they respond, in whole or in part, to each other? It seemed interesting to us to undertake an exploration of questions which are at the same time conceptual, historical and very immediate. Perhaps surprisingly, it appears that even conflict is a collaborative process. Even in a world of conflict, the other is a necessity.